Asthma, Cancer and neoplasms

People With Asthma May Have a Higher Risk of Cancer—And Not Just Lung Cancer

People With Asthma May Have a Higher Risk of Cancer—And Not Just Lung Cancer

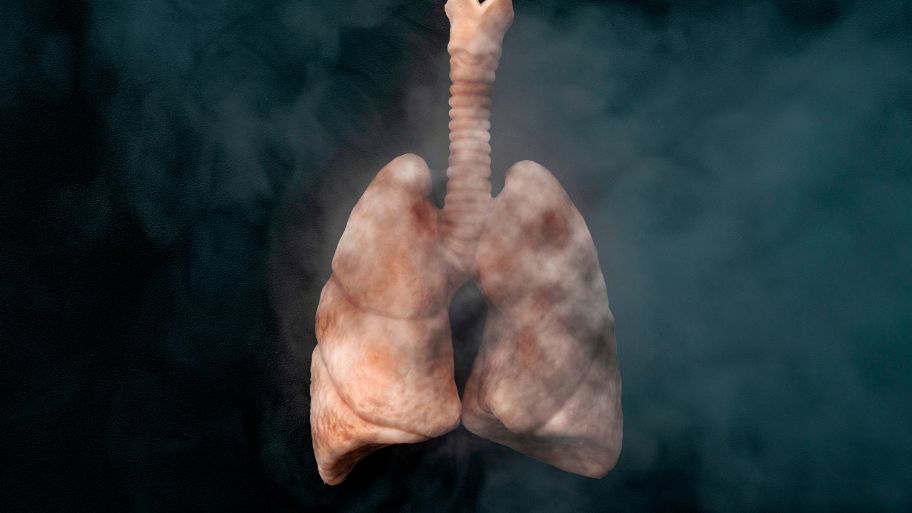

Recent research has indicated a potential link between asthma and an increased risk of developing cancer. According to a study conducted by researchers at the University of Florida, individuals with asthma have a 36% higher likelihood of developing cancer compared to those without respiratory disease. Specifically, the study found a higher risk of lung, blood, melanoma, kidney, and ovarian cancers among asthma patients.

The study aimed to explore the association between asthma and subsequent cancer risk by analyzing electronic health records and claims data from a large database called the OneFlorida+ clinical research network. The data encompassed over 90,000 adult patients with asthma and more than 270,000 adult patients without asthma. Using Cox proportional hazards models, the researchers examined the relationship between asthma diagnosis and the risk of developing cancer.

It is important to note that this study only established an association between asthma and cancer risk and does not imply a causal relationship. Further research is necessary to investigate potential causal relationships and the underlying mechanisms that may contribute to this association.

The findings of this study contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic and highlight the need for more extensive research in this area. It is essential to understand the implications of these findings and to conduct further studies to examine the causal relationships and risk factors involved. At present, these results do not have any immediate impact on clinical care.

The Impact of Inhaled Steroids

While the study suggests an overall elevated cancer risk in asthma patients, the results also indicate that asthma patients using inhaled steroids have a relatively lower cancer risk compared to those not using inhaled steroids. The analyses revealed that cancer risk was higher for several types of cancer in asthma patients without inhaled steroid use but lower for a smaller number of cancer types in those using inhaled steroids. This suggests a potential protective effect of inhaled steroid use on cancer development.

However, it is important to note that the study did not have a comprehensive measure of "managed asthma." Further research is needed to examine the causal relationship between asthma, inhaled steroid use, and cancer risk. While the findings support the potential role of chronic inflammation in cancer risk, it is still necessary to investigate other factors that could contribute to the association.

Previous studies have also suggested that inhaled steroid use may lower the risk of certain lung cancers. The current study’s findings are promising but inconclusive, particularly regarding the potential association between inhaled steroids and a lower risk of non-lung cancers. Further focused studies are required to determine the validity of this association.

It is crucial for individuals with asthma not to modify their use of inhaled corticosteroids based solely on the results of this study. Inhaled corticosteroids are essential controller therapies for persistent asthma, and their positive benefits in reducing asthma exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality far outweigh any modest effect on cancer risk suggested by this study.

But Additional Research Is Needed

Dr. Evans highlighted that previous studies have explored the potential increased risk of lung cancer in people with asthma, with most studies suggesting a small elevated risk for certain types of lung cancer. However, he emphasized the importance of recognizing the limitations of each study in providing definitive answers.

Regarding the University of Florida study, Dr. Evans pointed out certain features that may limit its ability to draw firm conclusions. The analysis was conducted retrospectively, meaning the researchers relied on previously collected data for their assessments. This approach introduces challenges such as missing data and the inability to assess certain risk factors.

Additionally, the patients with asthma in the study differed from the non-asthma group in significant ways. For example, the asthmatic patients were more likely to have other known risk factors for cancer, such as smoking or a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). While these issues do not invalidate the study’s conclusions, they indicate the need for further investigation to verify the results.

Lowering Your Risk of Cancer

Despite the current uncertainties surrounding the connection between asthma and cancer, Dr. Evans remains optimistic that ongoing research efforts will contribute to the development of definitive studies in the future.

In the meantime, he advises individuals with asthma to prioritize smoking cessation and stay up-to-date with vaccinations to prevent asthma exacerbations and minimize their risk of cancer.

Dr. Evans emphasized the significance of addressing the question of whether asthma influences cancer development, considering the substantial number of people affected by asthma and the profound impact of cancer as a disease.