Blood

Blood, Guts, And A Glimpse Of God

BOSTON — Some pro wrestlers are realer than others. A typical career, especially in the U.S., calls for a wrestler to flip from good guy to bad guy and back again, depending on the stories being told, and as such calls greater attention to the fact that they’re playing a role. But other wrestlers’ career arcs, especially in Japan, are the story. In keeping with the major Japanese promotions’ desire to present their product more as fictionalized sports than a reality show, these wrestlers are allowed to be changed much more gradually, and as a natural result of their success or failure. Kazuchika Okada, to give an example, has been over the past decade a brash young talent, then an imperious champion, and then a lost soul rediscovering his identity amid betrayal and change, and now, brilliantly, the hard-ass gatekeeper who won’t give an inch to the new generation that measures itself against him. It’s meant to be a natural progression of a man’s life; it couldn’t be further from the week-to-week soap operas of WWE.

For me, this consistency in a wrestler’s on-screen presentation does two things: It believably blurs the line between character and performer, and it makes these men feel larger than life, almost like archetypes. I can suspend my disbelief for them in a way I can’t quite do for those in America, even ones I really admire, who maybe once a year suddenly show up on TV as somebody very different. And if I can suspend that disbelief for a wrestler who appears to me like a superhero on my screen at home, it’s nearly impossible to pass up a chance to see them in the flesh.

So, that’s why I took a train to Boston to see Kota Ibushi wrestle in a giant cage in two rings with nine other people.

Ibushi, now 41 years old, might be in the epilogue of his hero’s journey. He was in the mid-aughts a little twink with Warped Tour hair in the smaller promotion DDT, until by 2021 he looked like a marble sculpture holding NJPW’s top prize. In between, he made waves and fans as a self-taught free-spirit who seemingly never had to actually work for money and could thus follow his own idiosyncratic ambitions. In DDT he began a career-defining partnership with Kenny Omega as the tag team the Golden Lovers, and the two either integrated their real romantic relationship into wrestling or made it up and then for years closely guarded any personal detail that might contradict it. He was rumored to have been banned from Budokan after doing a backflip off a balcony in 2012. When he rejected an offer from WWE after a few matches in 2016 he went back to New Japan not as Kota Ibushi but as the character “Tiger Mask W.” He spoke, with apparent seriousness, about how going to sleep one hour later each night means his days last 25 hours. He shot fireworks at himself while standing atop a car on the streets of London. He took an infamously horrific bump around his neck in 2019, finished the match, and didn’t take any time off. When he said I will win the title he actually said “I will become God.” Against the stolid backdrop of the 50-year-old traditions of New Japan Pro Wrestling, Ibushi was like Peter Pan: unpredictable, dangerous, queer, and forever young.

Then in October 2021, after a year where being a live entertainer felt almost impossible, Ibushi injured his arm in what could have been the match of the year against Okada. This time, he could not simply keep going. The match was stopped, Okada was declared the winner, and Ibushi didn’t step into a ring again until March of 2023. He worked on getting back to full health. He let his NJPW contract lapse while publicly speaking out against the company. When he finally reappeared, looking a bit weathered for the first time, it was for two matches at the Ukrainian Culture Center in Los Angeles over WrestleMania weekend, performing not for any company with a TV deal, but for top indie GCW. He is carefully choosing what opportunities interest him. His next match was announced only last week by AEW, who reunited him with Omega for their annual Blood And Guts—War Games, for the lapsed fan—and made him part of a five-man team in a ridiculous gimmick match crafted for car-crash intensity and viral stunts.

My desire to see Ibushi at this show is something different than other times I’ve sought to be in a room with a particular famous person. Unlike most concert tickets I buy, this isn’t a nostalgia thing. I didn’t even know who Ibushi was for most of his career. (I do feel some relief about this, because it means not all of my tastes were calcified as a child.) It’s not really enjoying someone’s recent work and wanting to see more of it, either; Ibushi barely has any recent work. And it’s not like when I bought a ticket specifically to see Denzel Washington on Broadway, to watch a great artist showcase his craft in a different context. I didn’t even really give thought to whether the match itself would be good or not.

What brought me to Boston was inspiration, which is the feeling I’d had watching Ibushi at his best. I tend to view masculinity with suspicion and nervousness, but under Ibushi’s control, it becomes something beautiful—strength and determination tinged with creativity and just the right amount of boyish silliness. If I were a man, this perception I have of Ibushi is what I would aspire to. As I am, I feel compelled to know it better. Coming to this show was about having faith that this person I want to believe is real actually does exist, in some form.

An odd thing about the Blood And Guts show was that, until the main event, you couldn’t really look the wrestlers in the face. There were zero screens in the arena showing close-ups of the action. The big cage looming above the ring, keeping you aware of what was to come, took the jumbotron out of commission, and for whatever reason AEW’s own screens only displayed graphics and backstage segments. This was uncharted territory for me in an arena the size of TD Garden, and it required some reconditioning on my part. From my spot in the very back of the lower bowl, I had to focus exclusively on the real-life, tiny-looking wrestlers in the distant center of this building, because a wandering eye could keep me from witnessing a key moment. But I stayed in this mindset even once the television feed entered the presentation for the main event, believing that it would bring me closer to the “authentic” thing, even though there’s an argument to be made that through a screen is how modern pro wrestling is meant to be experienced.

The actual Blood And Guts match, between the Blackpool Combat Club and Ibushi’s Golden Elite, turned out to be the weakest of the show, preceded as it was by the erotic supernova that was Hook vs. Jack Perry and the immersive comedy theatre of Adam Cole and MJF. (We won’t dignify the 66 seconds Tony Khan left for the women’s division.) But it was still a match that understood its formula perfectly. Blood And Guts/War Games, if you’re unfamiliar, features two adjacent rings surrounded by one large cage and starts with one man from each team. Then every couple minutes a new man runs in. If the promotion isn’t stupid, it gives the villainous team the man-advantage, so when a new wrestler enters, they beat up the good guy for a while until a hero arrives to even the odds. Repeat this until all 10 men are in, fighting not to a pinfall but until one surrenders.

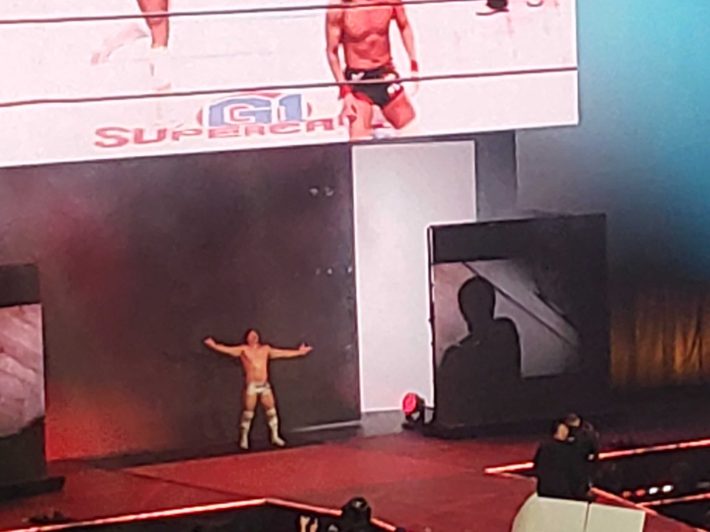

This classic psychology was pulled off to a T, with a few violent flourishes like Jon Moxley stuffing Nick Jackson’s mouth with “broken glass” and then stomping on his face. Ibushi’s appearance was, smartly, saved for last. While I got antsy and a bit uninterested by the other nine guys as I was waiting for him to show, I wasn’t disappointed when the final hero’s moment arrived. I stood and gazed upon the distant ramp as a familiar, beautiful silhouette stepped onto the stage and spread his arms wide, like he was welcoming us all to his house, and not the other way around. Journalistic integrity demands that I tell you I felt a little bit like I might throw up, in a way I associate with teenage first kisses. I don’t think I was alone. A medium-sized “Golden Lovers” chant struck up later in the match—a phrase you wouldn’t know if you only watched wrestling on basic cable—assured me that many in this crowd of eight or nine thousand were there for the same reason as me.

Ibushi’s best moment came right after his entrance. There was—stay with me a moment—a bed of nails in this match, and the BCC were using it to torture Omega while enjoying the 5-on-4. But after Ibushi entered the cage, he zeroed in on rescuing Omega, and, like Darth Vader on the Tantive IV, slowly, purposefully strode across the rings, dealing damage that climaxed in a standing backflip onto a prone Moxley strewn across the nails. It was a dramatic payoff after all those years Kota and Kenny spent on different sides of the world. All it was missing was “My Boyfriend’s Back” by The Angels on the PA.

Ibushi got a couple more moments of shine, most memorably a stretch where he circumnavigated the cage breaking up BCC submission holds on all his teammates. The match eventually ended because the BCC couldn’t properly wield the power of friendship. Two of their guys got pissed at the other three and left, giving the Golden Elite their first numbers advantage of the night, which they used to obtain victory.

I tried keeping my eye on Ibushi as much as possible throughout the chaotic action, but he got drowned out a bit by the sheer noise of Blood And Guts. Fans who watched on TV definitely observed that his once razor-sharp body and mutant athleticism had rusted in the time away. (Omega also noted to the crowd after the show that Ibushi had just traveled for 25 hours to be in Boston.) I didn’t quite think about that at the time, but I will say that I had no great life epiphany while watching Ibushi. He didn’t, from my hundreds of feet away, constantly carry around an aura that hinted at the limitless potential of mankind. There was nothing I could grab hold of. If I had seen him at this distance without context, I don’t think I would have recognized Ibushi as the superhuman who enthralled me in two dimensions. He looked like one of 10 little men I was viewing from very far away. Maybe because of this, because of how human he seemed, I let my attention switch to the big screen for the Lovers’ triumphant post-match reunion.

Even if my pilgrimage to Blood And Guts didn’t make me a better or more enlightened person, it did make me a happier one. The very last thing I saw of this man I traveled so far to see—the last image I’ll likely ever have of him live—was unmistakably him. Before leaving the cage, after the cameras stopped rolling, Ibushi picked up some loose thumbtacks and flung them into the air like confetti. Then, because of some puckish whim or because he knew that’s what we came to see or maybe just because he could, he threw himself down to the mat and embedded the tacks in his back. That boy, I would recognize anywhere.