Infection

People Who Don’t Get COVID Symptoms Share a Common Feature

Nearly 7 million people have died from COVID-19 since the outbreak of the deadly coronavirus more than three years ago. And yet even after repeat infections, a number of individuals are yet to experience a single symptom after contracting SARS-CoV-2.

A variant in an immune response gene may explain why, paving the way for more effective vaccines and treatments.

Global research led by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) found one in five people who were asymptomatic following an infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus carried the gene variant HLA-B*15:01.

In addition, UCSF neurologist Jill Hollenbach and colleagues found people with HLA-B*15:01 who had never been infected with the virus had immune cells that reacted to SARS-CoV-2 protein fragments, suggesting immunity developed after exposure to other infections.

Research suggests at least 20 percent of SARS-CoV-2 infections are asymptomatic, so learning more about this could help scientists in the fight against the disease that continues to take lives around the world.

“Most global efforts have focused on severe illness in COVID-19,” Hollenbach and the team write in their published paper.

“Examining asymptomatic infection provides a unique opportunity to consider early immunological features that promote rapid viral clearance.”

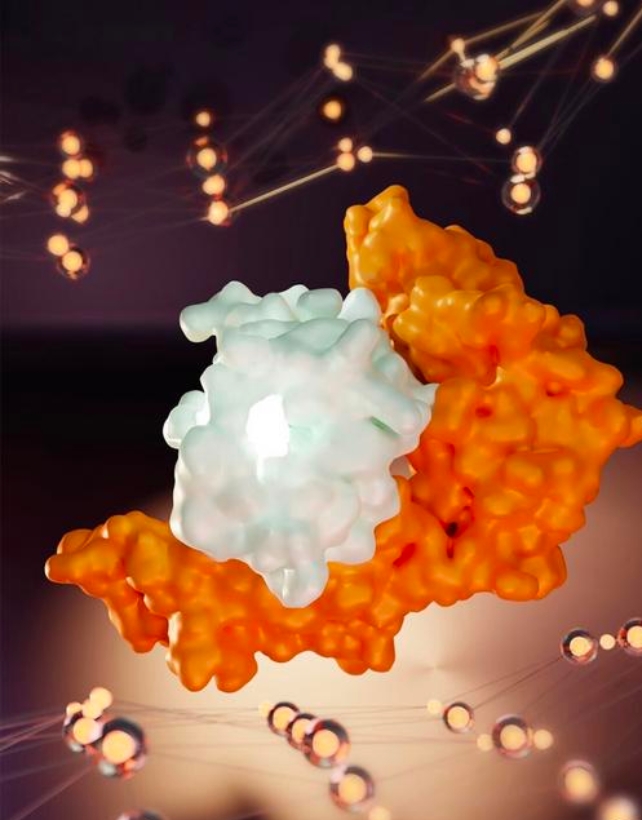

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes produce immune system-supporting proteins, and some HLA molecules are found on cell surfaces. They name and shame foreign invaders, for instance viruses, presenting miniature fragments to help immune cells like ‘killer’ T cells recognize and fight infection or disease.

“If you have an army that’s able to recognize the enemy early, that’s a huge advantage,” Hollenbach says; “it’s like having soldiers that are prepared for battle and already know what to look for and can tell by the uniform that these are the bad guys.”

The researchers examined genetic data collected previously from 29,947 registered bone marrow donors, to see if HLA variation might predispose people to asymptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 data came from a voluntary smartphone-based program that these donors participated in, tracking infection, symptoms, and outcomes.

There were 1,428 unvaccinated donors who reported testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, and of those, 136 said they had no symptoms.

One hint at a genetic connection was the discovery that 20 percent of these infected but asymptomatic donors carried at least one copy of the HLA-B*15:01 gene, compared to 9 percent of infected people who developed symptoms.

Having one copy of the protective HLA-B*15:01 variant doubled a person’s likelihood of being symptom-free when infected with COVID-19, and someone with two copies was eight times more likely to show no symptoms.

“Asymptomatic people might enable us to identify new ways of promoting protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection,” says biochemist Stephanie Gras from La Trobe University in Australia, “by mimicking this immune ‘shield’ observed in individuals that can dodge COVID-19.”

Further analysis found T cells from people with HLA-B*15:01 who had never been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (from blood donations collected prior to the pandemic), had a strong immune response to SARS-CoV-2 protein fragments.

These fragments shared genetic sequences with other seasonal coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Their T cells could recognize various COVID-19 variants, including Omicron variants.

“So, even if the bad guys changed the uniform, the army would still be able to identify them by their boots or maybe a tattoo on their arms,” explains University of North Carolina immunologist Danillo Augusto.

“That is how our immunological memory works to keep us healthy.”

The study has limitations; symptoms were self-reported, and the analysis only included individuals who self-identified as White.

The HLA-B*15:01 gene variant is quite frequent, appearing in about 10 percent of Europeans, but it may be less common in other populations, so larger and broader studies could provide more reliable conclusions.

Nonetheless, these significant findings could lead to ways to manage this still devastating disease.

“Our results have important implications for understanding early infection and the mechanism underlying early viral clearance,” the team writes, “and may lay the groundwork for refinement of vaccine development and therapeutic options in early disease.”

The peer-reviewed research has been published in Nature.