Infection

Vir antibody drug aimed at influenza A fails in clinical trial

Vir Biotechnology said Thursday that a long-acting antibody drug designed to protect healthy individuals from influenza A failed to do so in a nearly 3,000-person clinical trial.

Volunteers who received the highest dose of the drug, known as VIR-2482, were only 16% less likely than the placebo group to develop symptomatic influenza A infections, as defined by trial criteria, over a seven-month period. The difference was not statistically significant.

The results are a setback in broader efforts to develop better protective measures against both seasonal and potential pandemic influenza strains. In the short term, Vir and outside experts hoped VIR-2482 could provide additional annual protection for at-risk groups like older adults, as flu vaccines are often only modestly effective.

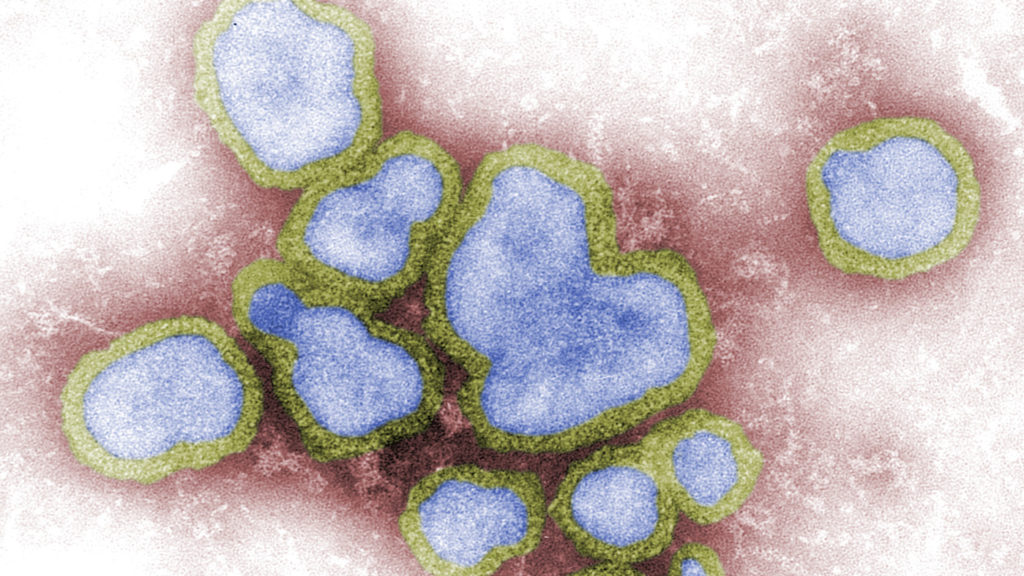

In the long term, the drug could have provided a potent pandemic countermeasure. Influenza A, which also affects animals, is the only type of flu known to cause pandemics, and VIR-2482 was designed to protect against every known strain since the 1918 Spanish flu.

“Although these topline data are disappointing, further analysis is necessary to better understand these outcomes, which we plan to present at a major medical congress,” said Vir Chief Medical Officer Phil Pang.

It’s also another setback for Vir in its efforts to build off its success during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the startup developed a blockbuster antibody for early-stage infections.

VIR-2482 was one of a small handful of programs the infectious-disease-focused biotech had when it went public in 2019. Studies on the drug were delayed as circulating levels of flu practically vanished during Covid.

Another program from that time, an experimental HIV vaccine, showed disappointing data in an early study, although the company is moving ahead with a second-generation candidate.

Vir’s stock was down 40% in pre-market trading Thursday, representing slightly over $1 billion in lost valuation.

Vir already has another flu antibody in development. Called VIR-2981, it is aimed at a different part of the flu virus and meant to protect against both influenza A and influenza B.

The company did see one flash of efficacy: A 57% reduction in symptomatic infections when it used symptom criteria laid out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which was a secondary endpoint. It did not say whether that result was statistically significant.

The CDC defines symptomatic infection as having a fever in addition to a cough or sore throat. The trial protocol used more expansive criteria, requiring one respiratory symptom, such as cough or sore throat, and one systemic symptom, such as fever or chills. For both endpoints, Vir also required PCR tests to confirm an influenza A infection.

Myron Cohen, global health director of the University of North Carolina Institute for Infectious Disease and Global Health, said the results should help researchers design better flu antibodies in the future. The flu has always been a hard virus to target because it shape-shifts so easily, making it difficult for scientists to hone in on an Achilles’ heel. He said Vir likely simply went after the wrong part of the virus.

Antibodies “are a fantastic tool for prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. Covid 19 taught this lesson. But developing the best mAbs is an exploratory process so all results must be used iterative[ly],” Cohen said in a text message, using a common shorthand for monoclonal antibodies. “The clinical trial results presented by Vir are one step in identification of the best mAbs for prevention and treatment of influenza.”