Blood

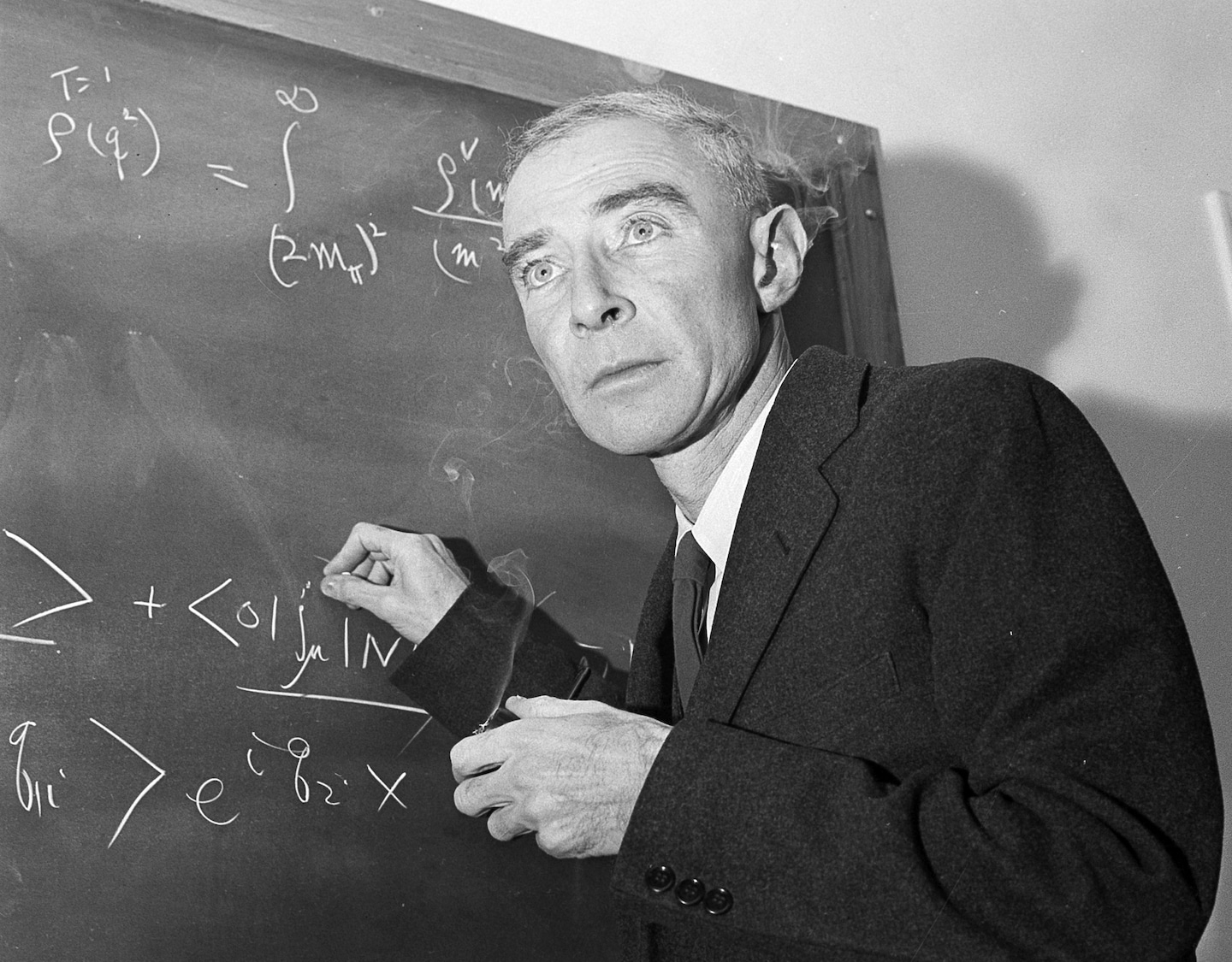

Oppenheimer met the president after atomic bombs: ‘I have blood on my hands’

The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima had pulverized life and changed the world, and J. Robert Oppenheimer celebrated by clasping his hands like a prize fighter, soaking in the roaring applause from the crowd in Los Alamos, N.M. It was a thrilling time for Oppenheimer, who told the crowd in August 1945 in the place where the bombs were designed and built about his only regret: not that thousands of people had been killed, but that “we hadn’t developed the bomb in time to use it against the Germans” earlier in World War II.

But Oppenheimer’s feeling of triumph evaporated in the months after the destruction of Nagasaki, caused by another atomic bomb three days after Hiroshima, that the scientist believed was unnecessary and unjustified. His revulsion was so evident on his face that President Harry S. Truman asked him what was the matter when they met at the White House for the first time in October 1945.

“Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands,” Oppenheimer told Truman, according to “American Prometheus,” the 2005 Oppenheimer biography from authors Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

While Truman assured Oppenheimer he should not carry the burden of the bombs — “I told him the blood was on my hands, to let me worry about that” — the president was privately infuriated by what he described to aides as a “crybaby scientist” and the regret he had over the decimation, according to author Ray Monk’s 2012 biography, “Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center.”

“Blood on his hands, dammit, he hasn’t half as much blood on his hands as I have,” Truman said afterward. “You just don’t go around bellyaching about it.”

Truman later told Dean Acheson, his secretary of state: “I don’t want to see that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

It was the only time the two would meet, and Oppenheimer believed he had missed perhaps his only chance to avert a potential nuclear arms race that could slaughter hundreds of millions of people.

“He didn’t convince the president, and the president didn’t like him, unfortunately,” Charles Oppenheimer, the physicist’s grandson, told The Washington Post. “My grandfather gave the right advice, and the president didn’t take it. What he said about having blood on his hands was clearly something Truman didn’t like.”

Almost 80 years after the nuclear weapons were detonated in Japan, the life and legacy of the man known as “the father of the atomic bomb” is being reexamined thanks to Christopher Nolan’s new film, “Oppenheimer,” which premieres nationwide on Friday. The film, based on Bird and Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, has won early critical acclaim as a “supersize masterpiece” that Nolan says has left some moviegoers exiting the theater feeling “absolutely devastated.”

“I view Oppenheimer as the most important person who ever lived,” Nolan told “CBS Sunday Morning.” “Oppenheimer’s story is one of the biggest stories imaginable. By unleashing atomic power, he gave us the power to destroy ourselves that we never had before, and that changes the human equation.”

The interest surrounding Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, has hit a fever pitch in the run-up to the movie. Some historians say the war between Russia and Ukraine — and Russia’s repeated threats that it could use nuclear weapons — make Oppenheimer’s outlook on such weaponry as relevant today as it was decades ago.

“The movie is generating a huge amount of interest because Oppenheimer now is, in some ways, a figure of our times,” Monk, the biographer and professor emeritus of philosophy at the University of Southampton, told The Post. “Because of his central role in the atomic bomb and the arguments about the atomic bomb in years following the Second World War, interest in him has been revived as someone who symbolizes an issue that is still occupying us.”

Charles Oppenheimer, 48, who never met his grandfather but has become a family spokesman and a founding member of the Oppenheimer Project, added, “He saw how the world had changed, and he saw it coming. It wasn’t a surprise. The reason he’s so relevant is not related to just atomic bombs but also the state of humanity.”

The depression and overwhelming anxiety J. Robert Oppenheimer felt during the development and testing of the bombs appeared to dissipate on Aug. 6, 1945, after one word was shouted by the announcer at the Los Alamos Laboratory.

“Now!”

A tremendous burst of light was followed by a deep growling roar of the explosion over Hiroshima, according to author Ferenc M. Szasz’s 1984 book, “The Day the Sun Rose Twice.” An estimated 135,000 people were dead. Oppenheimer was relieved — and feeling himself.

“I’ll never forget his walk,” Isidor Rabi, a close confidant and colleague of Oppenheimer’s, recounted in Monk’s book. “I’ll never forget the way he stepped out of the car. … His walk was like ‘High Noon’ … this kind of strut. He had done it.”

His mood changed three days later, when the FBI described Oppenheimer as a “nervous wreck” over bombing Nagasaki, which he argued was not justified from a military perspective. The second atomic bomb was dropped on Aug. 9, 1945, and another estimated 64,000 people were killed.

Oppenheimer, whose crippling remorse had him smoking constantly after the Nagasaki bombing, delivered a letter to Secretary of War Henry Stimson on Aug. 17, 1945, urging that nuclear weapons be banned. Oppenheimer resigned as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory after the war ended.

The White House meeting with Truman on Oct. 25, 1945, was Oppenheimer’s opportunity to persuade the president to address a potential international issue with Russia over the use of nuclear weapons. Truman was curious to meet Oppenheimer, who he heard was charismatic and eloquent, and hoped he could get Oppenheimer’s support in helping Congress pass the May-Johnson Bill, which would give the U.S. Army permanent control over atomic energy.

“The first thing is to define the national problem, then the international,” Truman told Oppenheimer, according to Monk.

The physicist thought what the president said was foolish and wrong — very, very wrong — and pushed for international controls over all atomic technology.

“He went into the October meeting with strung-out nerves realizing he didn’t have many chances left,” Oppenheimer’s grandson said.

Oppenheimer was perplexed when Truman asked him to guess how long it would take for the Russians to develop their own atomic bomb. When Oppenheimer said he did not know, historians say Truman offered a one-word answer: “Never.”

It was around this time that Oppenheimer wrung his hands together and told the president that it felt as if he had blood on his hands. A long and incredibly awkward silence followed.

There are differing accounts of how Truman responded, according to “American Prometheus.” One account had Truman replying to Oppenheimer by saying, “Never mind, it’ll all come out in the wash.” Another account Bird and Sherwin detailed had Truman pulling out a handkerchief from his breast pocket and offering it to Oppenheimer.

“Well, here, would you like to wipe your hands?” Truman asked.

The meeting concluded after Oppenheimer voiced his concern. They shook hands, and Truman left Oppenheimer with reassurance, Bird and Sherwin wrote: “Don’t worry, we’re going to work something out, and you’re going to help us.”

The experience stayed with Truman, who wrote months later that Oppenheimer had “spent most of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them because of the discovery of atomic energy,” according to “American Prometheus.”

“Truman was incredibly annoyed that Oppenheimer would take responsibility when it was Truman’s responsibility for the bombing,” Monk said.

Truman still honored Oppenheimer in 1946 with a presidential citation and a Medal for Merit, with Stimson describing the development of the atomic bomb as “largely due to [Oppenheimer’s] genius and the inspiration and leadership he has given to his colleagues.”

Charles Oppenheimer said he had asked his father, Peter — J. Robert Oppenheimer’s eldest child — about the exchange, and that his father’s theory was that the physicist was “trying to impress” Truman on some level.

“With Truman, he thought he was a peer,” Charles Oppenheimer said. “There were certain people who Oppenheimer felt he could talk to like that. … But he was overruled by a high school-educated gut feeling from Truman.”

He added: “I care a lot about this when people are portraying my grandfather as a crybaby and not recognizing the reality of what happened.”

Monk, who spent 11 years writing his book, said interest surrounding J. Robert Oppenheimer is “higher than it’s ever been.” For Charles Oppenheimer, the increased attention has been surreal. He has seen the movie — and loved it. The spotlight on the grandfather he never met, and the meeting with Truman, has been a reminder that being an Oppenheimer means “there is a duty and heaviness to use the name to deal with the problems in the world.”

“He was the type of guy to do his duty,” Charles Oppenheimer said. “And whether it succeeded or failed, he needed to try.”