Blood

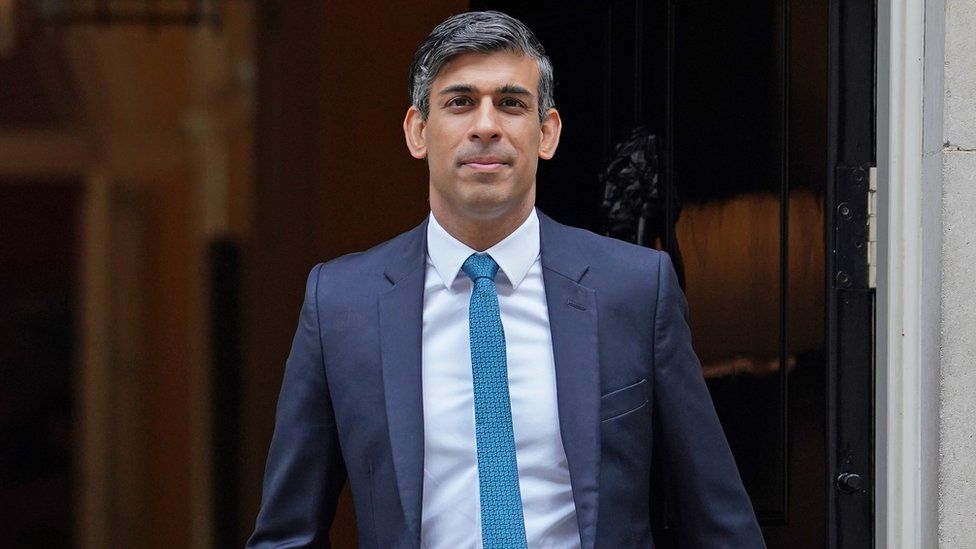

Infected Blood Inquiry: Rishi Sunak to give evidence

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will appear in front of the Infected Blood Inquiry on Wednesday.

Bereaved families want Mr Sunak to accept compensation recommendations made three months ago by the inquiry’s chairman, Sir Brian Langstaff.

It is thought that 30,000 people in the UK were given contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 80s.

Some victims have received financial support but not all have been fully compensated.

The inquiry has recommended the Government establish an arms-length compensation body as soon as possible, and definitely before the final report in the autumn.

What is the infected blood scandal?

The inquiry was established to examine how thousands of patients in the UK were infected with HIV and hepatitis C some 40 years ago, how authorities – including government – responded, and whether there was a cover-up.

Thousands of NHS patients with haemophilia and other blood disorders became seriously ill after being given a blood transfusion or a new treatment called factor VIII or IX from the mid-1970s onwards.

At the time, the medication was imported from the US, where it was made from the pooled blood plasma of thousands of paid donors, including some in high-risk groups, such as prisoners and drug users.

If a single donor was infected with a blood-borne virus such as hepatitis or HIV, then the whole batch of medication could be contaminated.

About 2,900 people died in what has been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Now the families of those affected want Downing Street to respond to the compensation recommendations made by the inquiry – which some are speculating could cost the government billions of pounds.

- Bereaved relatives in government compensation plea

- Parents and children ‘should get blood payout’

- Infected blood inquiry: Five things we have learned

They have already written a letter to No 10, asking for urgent action on the payments.

When running for Prime Minister in July 2022, Rishi Sunak called the contaminated blood scandal a “tragic injustice” and promised to provide certainty to survivors.

Leader of the House of Commons, Penny Mordaunt, has already given evidence to the inquiry this week – she was formally the minister responsible as paymaster general between February 2020 and September 2021.

She said the Covid pandemic had been “all-consuming” but added that the government had not been dragging its feet over paying compensation.

This was backed up by current paymaster general Jeremy Quin, who, when giving evidence on Tuesday, said he was determined to “redress” amid anger over fears that the delays are because compensation is deemed too expensive and complicated.

One of those affected is Gwynneth Walker, whose son Steven died aged 37 in August 2017.

He died as a result of receiving contaminated blood products, having been infected with hepatitis C and HIV as a child, while receiving treatment for haemophilia.

Hepatitis C is a virus that can infect the liver and has flu-like symptoms.

It is mostly possible to cure, with modern treatments.

HIV is human immunodeficiency virus, which damages the cells in your immune system and weakens your ability to fight everyday infections and diseases.

It has no cure, but does now have effective treatments that allow people to live a relatively normal life.

Ms Walker told the BBC the infections that Steven had, along with the stigma associated with them, “absolutely blighted the whole of his life”.

“They ruined every opportunity that he may have had otherwise.

“From the opportunity to learn at school, to go to college, to start a career, to have a girlfriend, to be able to get married, to have children, be a father, he wanted all of those things, and had none of them.”

Ms Walker added: “Watching my child being poorly for all those years and eventually dying has been a blight on my life.

“I was in my 20s when this happened to my little boy and here I am, a pensioner, still without justice served,” she said on the subject of compensation.

Ms Walker said that while no proper justice can be served, the only help can be in financial compensation, which she says would be used to help all members of her family, including her older children “who had to watch him [Steven] suffer for most of his life”.

Although Steven died before the inquiry began, Ms Walker says he was “delighted” when the announcement was made by Theresa May, in 2017, that a public inquiry would take place.

Related Topics

- UK contaminated blood inquiry

- NHS