Infection

Waterborne infections rise after hurricanes, decades of data show

July 29, 2023

2 min read

Source/Disclosures

Published by:

Disclosures:

Lynch and Shaman report being supported by grants from the NIH. Shaman and Columbia University are part owners of SK Analytics, and Shaman reports consulting for Business Network International.

Key takeaways:

- There are increases in some waterborne diseases following contact with hurricane storm water.

- Increasingly strong storms have also made flood risks more likely, increasing waterborne disease risk.

More than 2 decades of data show that exposure to tropical storm or hurricane rainfall increases the risk of acquiring waterborne diseases, demonstrating the storms’ threat to public health, researchers reported in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Experts have warned that climate change can affect the spread of infectious diseases, including through vectors like mosquitoes and ticks, which survive better in warmer climates.

Tropical cyclones occur seasonally along the East Coast of the United States, and have been the cause of extreme flooding, which can contaminate water sources and increase the risk for waterborne disease infections, according to the new study.

“Elevated case counts and outbreaks have been attributed to individual storms, but the effect of tropical cyclones on specific waterborne infections has not been evaluated over multiple storm seasons,” Victoria D. Lynch, PhD, an environmental epidemiologist, and Jeffrey Shaman, PhD, a professor of environmental health sciences — both at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health — wrote in the study.

“Understanding waterborne pathogen transmission is a pressing public health challenge because the burden of disease will likely increase in conjunction with an aging population, deteriorating drinking and wastewater treatment systems and increased storm-related flooding due to climate change,” they wrote.

Bacterial, parasitic and viral pathogens cause about 7.15 million cases of waterborne disease annually in the United States, according to the CDC, affecting about one in 44 people in the country.

These infections lead to roughly 601,000 ED visits, 118,000 hospitalizations, 6,630 deaths and $3.33 billion in direct health care costs, according to the agency.

Lynch and Shaman analyzed data collected between 1996 and 2018 for each U.S. state as part of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System to identify weekly cases of cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, Legionnaires’ disease, Escherichia coli infections, salmonellosis and shigellosis.

The researchers used exposure and case data to assess the effects of tropical cyclones on the six diseases using modeling, separately defining storm exposure for windspeed, rainfall and proximity to the storm’s track.

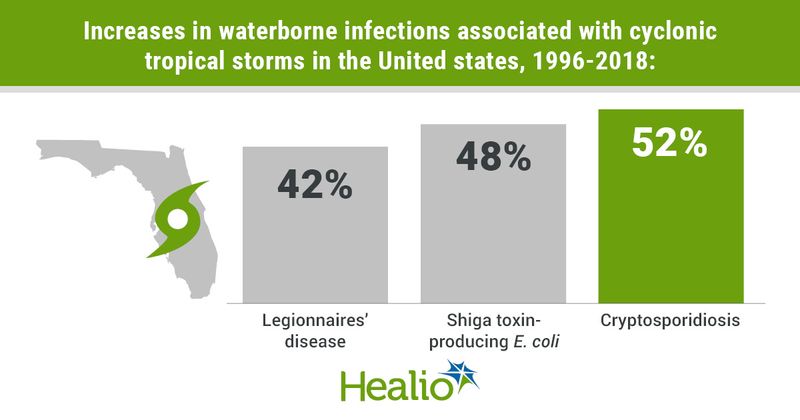

Overall, the researchers found that exposure to storm-related rainfall resulted in a 48% increase in Shiga toxin-producing E. coli infections 1 week after a storm, a 42% increase in Legionnaires’ disease 2 weeks after a storm and a 52% increase in cryptosporidiosis cases during storm weeks that then declined over ensuing weeks after the storm.

In comparison, the researchers found that rates of salmonellosis, shigellosis and giardiasis were either unaffected, or even decreased, during storm weeks and ensuing weeks. Salmonellosis was considered unaffected by storms because, in addition to the infection being predominantly foodborne, outbreaks often occurred at the same time as storm weeks, making it difficult to determine if they were storm related.

The researchers concluded that tropical cyclones are associated with waterborne disease, although it depends on exposure, strength of storm and pathogen biology, along with a host of other local concerns, such as drainage, potential for standing water and other infrastructure concerns.

With storm severity projected to increase as the atmosphere warms, the researchers suggest that developing a better understanding of the relationship between storms and infectious disease could help aid public health policies.

“We found that tropical cyclones represent a risk to public health in the United States, although findings for individual pathogens varied,” the researchers wrote. “The U.S. sanitation infrastructure is aging, and the country will likely experience more severe storm-related flooding as a result of climate change.”

“Thus, identifying the drivers of pathogen transmission, and opportunities for intervention, will be crucial to reducing disease burden after cyclonic storm events,” they wrote.