Infection

Brain-eating amoeba: Will the warming climate bring more cases?

(NEXSTAR) – Infections of brain-eating amoeba are on the rise — and the warming climate may only exacerbate the problem, according to one of the world’s preeminent experts on the subject.

“Yes, we are experiencing warmer temperatures, and these amoeba are thermal-tolerant … so the numbers of amoeba will be higher,” explains Dr. Dennis Kyle, the head of the cellular biology department at the University of Georgia and the scholar chair of antiparasitic drug discovery with the Georgia Research Alliance.

“Warmer climates means, yes, more exposure and more cases,” he added.

Kyle, speaking with Nexstar, confirmed that reported cases of Naegleria fowleri infection — more commonly known as an infection of brain-eating amoeba — have “significantly increased” over the past four to five years. But he warned that increased cases cannot be linked solely to warmer waters, but rather more awareness and fewer misdiagnoses than in previous years.

“There’s more recognition that these amoeba are possibly causing disease, when before, virologists were misclassifying these cases as bacterial meningitis or [other diseases],” he said.

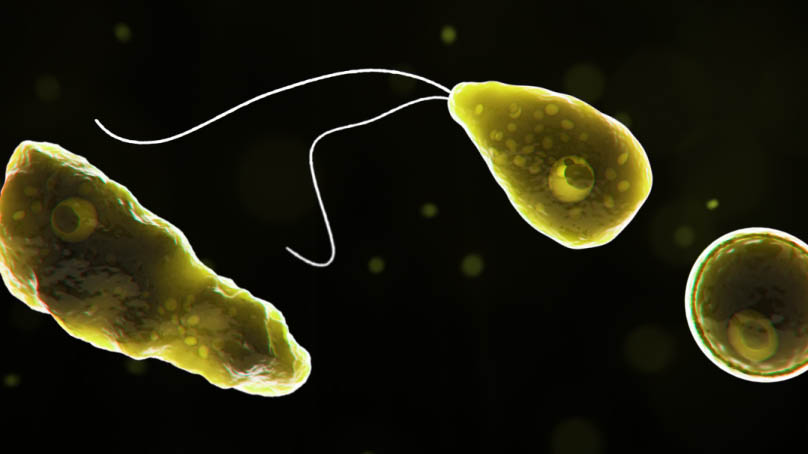

Naegleria fowleri, the microscopic organism responsible for the infection, is primarily found in warm freshwater and soil, but also hot springs, improperly chlorinated pool water, improperly treated tap water, and, in lower concentrations, even cooler freshwaters. Infection of N. fowleri usually occurs after water is forced into the nose, allowing the organism to enter the nasal cavity and cross the epithelial lining into the brain, where it begins destroying the tissue of the frontal lobe.

This brain infection, known as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), can lead to symptoms including fever, headaches, stiff neck, seizures and hallucinations within two weeks of exposure. It is almost always fatal, with death occurring within another one to 18 days of the first symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Most infections tend to occur between June and September, but cases outside of these months are not entirely unheard of, Kyle said.

N. fowleri is also found in higher concentrations in warmer, smaller bodies of freshwater, but the organism can be found in pretty much any freshwater lake, including cooler, clearer waters, Kyle said. There was even a case in 2016 in which a teenager contracted a fatal infection of N. fowleri after going whitewater rafting — an activity generally undertaken in less-risky colder waters.

The highest concentrations, though, are generally found in freshwater with surface temperature readings of 75 degrees F or higher, especially for extended periods of time.

And climate change, as scientists have observed, is already having an impact on the temperature of the world’s freshwater lakes. The quality and color of the water can also change due to warming temperatures, recent studies have suggested.

“There’s a constant risk in warmer climates,” Kyle remarked.

The amoeba itself can’t be specifically targeted with current treatments either, leading to a fatality rate of 97%. In fact, Kyle only knows of four known cases in the U.S. where patients survived, and “maybe” seven globally.

“I’m not convinced that were any further along in getting better treatment,” Kyle told Nexstar of the current antifungal and antibiotic cocktails that are currently used. “But If people can get diagnosed earlier, even with the suboptimal treatments that we have, they have a better chance of survival.”

To that end, Kyle, and the families of some of the victims, are hoping to spread awareness of the disease. He and his colleagues have also worked to identify what they believe is a biomarker that can help doctors diagnose infection earlier than previously possible, but their test is not yet FDA-approved.

“Most tests use cerebral spinal fluid, but we don’t have to have that,” he told Nexstar. “We can use blood or even urine. In our analyst studies, we can detect it three or four days before symptoms develop. I’m pretty excited.”

Preventing infection in the first place is currently the best course of action, he added.

“Raising awareness helps. But I think any warm freshwater facility, or hot spring … and at splashpads, you have to look at it carefully,” he said. “It’s incumbent on people running these facilities to minimize risk and minimize exposure.”

People can also take precautions by avoiding bodies of warm freshwater, and especially refraining from jumping or diving into such waters, which increases the risk of having contaminated water forced into the nose. He also recommends using nose plugs, keeping your head above the surface, and properly cleaning and chlorinating wading pools, swimming pools and spas (or opting for salt-water pools or spa facilities).

Parents should also know that children are at the highest risk of infection, but likely for no other reason than that they’re more prone to be more active in the water.

“It’s difficult to define the risk,” Kyle said. “But think of it like a lightning storm. Everybody knows not to walk outside in a lightning storm with a golf club in their hands. But many parents don’t know the risk that their kids might be open to.”

Suggest a Correction