Infection

Skin and soft tissue infections: risk factors and presentations

Skin and soft tissue infections encompass a wide range of infectious conditions affecting the integumentary system, including the epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous tissue and fascial planes[1]. The incident rate of these infections is 24.8 cases per 1,000 people[2].

There are various risk factors associated with skin and soft tissue infections and this article will focus on the identification of risk factors and the varied clinical presentations encountered, as well as the causative pathogens. These conditions can be recognised in the pharmacy or during another pharmacist-led service, such as routine GP practice appointments; therefore, it is important for pharmacists to have a comprehensive understanding of these factors. Early identification and referral of these conditions can minimise the risk of any complications and prevent further progression.

Risk factors

There are several risk factors associated with skin and soft tissue infections, the majority of which are outlined in Table 1. The most common ones include immunocompromised states, diabetes mellitus, healthcare-associated risks and community-related risks, which are discussed in more detail below.

Immunocompromised patients

Immunocompromised individuals, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cancer or on immunosuppressive medicines — including oral steroids or ciclosporin — have more than a 20% increased risk of skin and soft tissue infections[3,4]. This can be owing to low levels of infection fighting white cells, as well as breakdown of the skin resulting from medication or cancer radiation therapy, for example.

Diabetes mellitus

Particularly uncontrolled or poorly managed diabetes mellitus has been consistently identified as a significant risk factor for skin and soft tissue infections. The hyperglycaemic state compromises the immune response, impairs wound healing and increases susceptibility to infections, such as diabetic foot ulcers and cellulitis[5].

Healthcare-associated factors

Patients with prolonged hospital stays who have undergone invasive procedures or the presence of indwelling medical devices are at an increased risk of healthcare-associated skin and soft tissue infections. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other multidrug-resistant organisms commonly cause these infections[6].

Community-associated factors

Although not very common in the UK, living in crowded or unsanitary conditions, close contact with infected individuals and exposure to certain environments (e.g. recreational water sources) are associated with an elevated risk of community-associated skin and soft tissue infections, including methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) infections, which can occur in hospitals[7].

Diagnosis

History taking

A thorough history is beneficial to help diagnose skin and soft tissue infections and to identify the potential causative pathogens. This includes: social history, such as drug use and living conditions; past medical/surgical history; and drug and allergies history. For skin and soft tissue infections, a risk factor assessment can also be carried out, which may include history of surgery or trauma (e.g. injuries, insect or animal bites) or lesions on the skin[8].

Systemic symptoms of infection, such as general malaise, fever, sweats and chills, should be assessed using the National Early Warning System (NEWS) score to detect risk of clinical deterioration[8]. See Table 1 for common risk factors for skin and soft tissue infections[9].

Physical examination

Physical examination can aid in the diagnosis of skin and soft tissue infections and should include descriptions of the extent and location of erythema, oedema, warmth and tenderness.

The following should be considered when examining a potential skin and soft tissue infection, in order of severity:

- Systemic signs, in addition to fever, can include hypotension and tachycardia, which would prompt closer monitoring and possible hospitalisation. Lymphangitic spread also indicates severe infection;

- Bullae (i.e fluid-filled blister) can be seen in impetigo caused by staphylococci or in infection with Vibrio vulnificus or Streptococcus pneumoniae;

- Fluctuance (i.e fluid structure that produces a wave-like motion) indicates fluid and a likely abscess that may need incision and drainage;

- Purpura (i.e. small blood vessel haemorrhage) may be present in patients on anticoagulation therapy, but if it is accompanying a skin and soft tissue infection, it could be suggestive of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, especially from streptococcal infections;

- Depth of infection (see Figure 2);

- Crepitus (crackling or popping sensations as air moves around in the tissue) can be felt in gas-forming infections and raises the concern for necrotizing fasciitis and infection with anaerobic organisms such as Clostridium perfringens;

- Necrosis (i.e. tissue death) can occur owing to injuries, frostbite, blood clots or group A streptococcal infections[9].

Investigations

Blood tests can be taken in patients with suspected severe infections to monitor full blood count, C-reactive protein, urea and electrolytes and liver function tests in those requiring IV antibiotic administration[8].

Wound cultures, tissue biopsy, needle aspiration of any pus-filled lesions, wound swabs of abscesses or ulcerated lesions can be used to help identify pathogens based on severity and type of wound. Imaging therapy is typically not useful and therefore not commonly indicated[9].

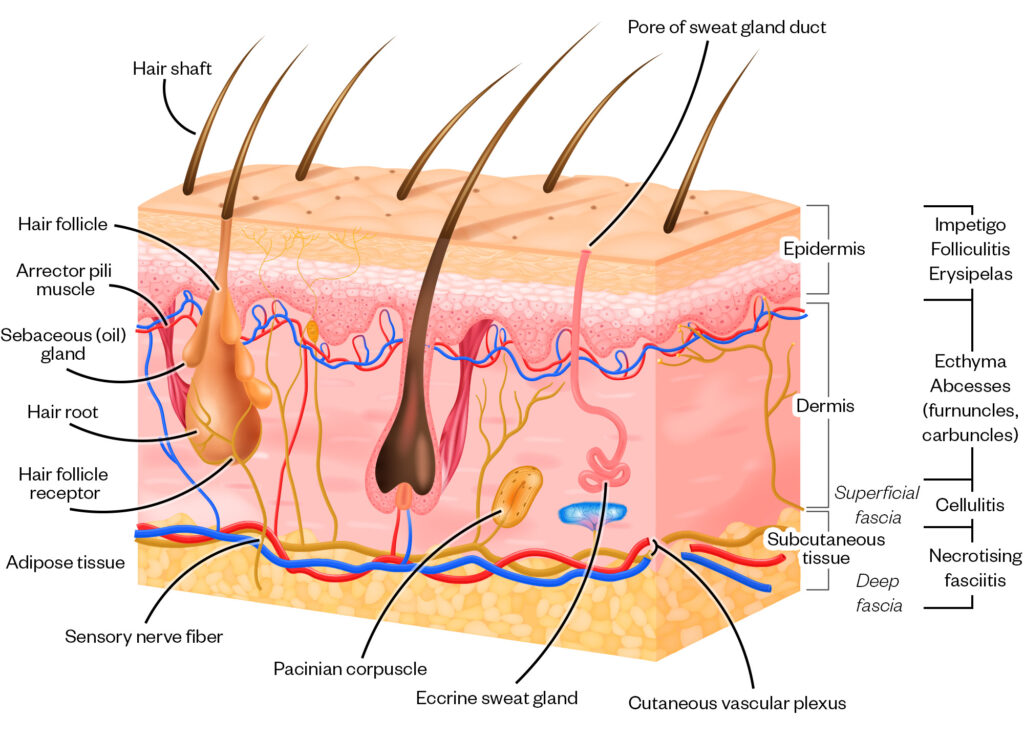

Figure 1 depicts the possible depths of involvement of skin and soft tissue infections and the accompanying diagnoses. Superficial infections — such as erysipelas, impetigo, folliculitis, furuncles (i.e. boils) and carbuncles (i.e. dome-shaped clusters of boils) — are located at the epidermal layer, while cellulitis reaches into the dermis[10]. Deeper infections cross the subcutaneous tissue and can potentially become more serious and can result in fasciitis[11].

Shutterstock.com/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Presentations and management of skin and soft tissue infections

Skin and soft tissue infections represent the second most prominent reason for prescribing antibiotic treatment, after lower respiratory tract infections[12]. For example, just under 19% of patients were treated for skin, bone and joint infection out of a sample of 3,483 patients[13]. Skin and soft tissue infection management will be guided by its severity of infection and severity is broadly correlated with how deep into the skin’s structure the infection has progressed, the extent of erythema, heat and duration of infection, as well as the pathogen involved[14].

Skin infection signs in people of colour can present differently when compared with white patients. For example, typical redness, inflammation and rashes can present violaceous in colour or darker than their natural skin tone. Subsequent healing of infections can often result in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, which may also need to be managed, as this can in itself cause significant distress. Images of presentations in darker and lighter skin tones have been included where relevant. Related information can be found in ‘Recognising common skin conditions in people of colour’.

Impetigo and ecthyma

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY (left) and Grook Da Oger CC-BY-SA (right)

Impetigo is a highly contagious superficial bacterial skin infection. It commonly affects

children and presents as small, red papules that progress to vesicles or pustules. The

vesicles or pustules rupture, leaving behind thick, honey-coloured crusts[15].

ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Ecthyma is a deeper form of impetigo that involves the dermis. It presents as a painful ulcer with a thick, adherent crust, surrounded by an erythematous halo. Ecthyma is commonly caused by S. pyogenes or S. aureus, including MRSA strains[16].

Management

Impetigo can be managed by topical or oral antibiotics that target the commonly associated bacteria, namely, S. aureus and S. pyogenes[14,17].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends managing impetigo and ecthyma through hygiene measures to help minimise the spread. Localised infection may be treated with topical hydrogen peroxide 1% or, if not suitable (i.e. if infection is close to the eyes or lesions show signs of infection), a topical antibiotic can be considered, such as fusidic acid 2% of if resistance if suspected then Mupirocin 2% can be used[18]. However, the BNF states mupirocin or fusidic acid should not be used for longer than ten days topically to minimise the risk of resistance[19].

For ecthyma, dermatologists recommend soaking crusted areas. Using a clean cloth soaked in a mixture of approximately 100ml of white vinegar in a litre of tepid water. The compress should be applied to moist areas for about ten minutes several times a day, before gently wiping off the crusts[18,20].

In widespread impetigo infection, patients that are systemically unwell, or at risk of complications owing to immunosuppression should be treated with a short course of oral antibiotics. Flucloxacillin 500mg four times a day for five days is the recommended first-line oral treatment option[18]. NICE advises on common sense measures to help minimise the spread as impetigo is easily passed on via close contact. Hygiene measures include washing, not sharing towels and not scratching the affected skin[21].

Folliculitis

MID-ESSEX HOSPITAL SERVICES NHS TRUST/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Folliculitis is a common bacterial infection of hair follicles that presents as small, tender, erythematous papules or pustules around hair follicles. It may occur anywhere on the body and is commonly caused by S. aureus[22]. However, folliculitis can be bacterial, fungal, viral, parasitic and of non-infectious cause[23,24]. Bacterial folliculitis is the most common type and, as a result, will be the focal point of this article.

Management

Patients can self-manage with the use of topical antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine, povidone-iodine or triclosan, which can be used for seven to ten days[25]. Fusidic acid is the preferred first-line topical treatment option owing to its narrow-spectrum antibacterial effect on staphylococcal infections[26]. A seven-day course of oral antibiotics is recommended if fever, cellulitis, facial lesions, severe pain and discomfort are present, or if there are comorbidities such as diabetes and immunosuppression[27].

Cellulitis and erysipelas

Cellulitis is a common bacterial infection characterised by inflammation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It presents as erythema, warmth, swelling and tenderness. The affected area may also show poorly defined borders. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species are the most common pathogens involved[1]. Risk factors of cellulitis include diabetes, weight management and emollient use in those with chronic/atopic dermatitis to minimise skin breaks[28].

Shutterstock.com

Cellulitis commonly affects lower limbs unilaterally with acute onset of red, painful, hot, swollen and tender skin that spreads rapidly, capable of significant spread over a 24-hour period. The presence of diffuse redness and well-demarcated edges can be marked with a pen to monitor its progress[28].

Severity of cellulitis can be classified using the Eron classification system (see Table 2)[29].

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO (left) and Edith Sophie KOMBO Bayonne CC-BY-NC (right)

Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that commonly affects infants and older people with similar risk factors to cellulitis. It affects the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics. It is a superficial form of cellulitis as it involves only the upper dermis and superficial lymphatic, whereas cellulitis affects the subcutaneous tissue and dermis[31,32]. It is characterised by a well-defined, raised and indurated erythematous plaque with sharp borders.

It typically occurs on the face or legs and is almost always caused by Streptococcus pyogenes[33]. Erysipelas is not graded using the Eron scale. General management includes use of cold packs and analgesia to ease discomfort, as well as elevation and wound care[31]. Oral or IV penicillin is the first-choice antibiotic and treatment should be for a 10–14 day duration[31].

Management

Class III and IV cellulitis warrant urgent hospital admission, as well as individuals with an extensive affected area that is spreading quickly. Additionally, those who are aged under 1 year, or who are frail and immunocompromised should be referred for urgent admission[28].

Class I can be treated in primary care with high-dose oral antibiotics:

- Flucloxacillin 500mg four times a day, orally, for five to seven days;

- For infection near eyes and nose — co-amoxiclav 500/125mg three times a day, orally, seven days[28].

The area of cellulitis should be marked with permanent markers by the patient to track the spread of infection. Rapid spread would warrant urgent hospital admission. Over-the-counter analgesics can be used for pain relief. Hydration is also advised and if the infected area is the leg(s) then elevation is encouraged to promote reduction of swelling; however, compression should be avoided[28].

Class II cellulitis may not require admission if there are facilities and expertise available in the community setting to give IV antibiotics and monitor the patient — local guidelines should be reviewed[28]. The underlying risk factors of cellulitis should be managed and controlled[28].

Abscesses

Shutterstock.com

Abscesses are localised collections of pus within the skin or subcutaneous tissues. They appear as painful, tender and fluctuant nodules. The overlying skin may be erythematous and warm to touch. Common pathogens involved include S. aureus, including both MRSA and MSSA strains, particularly in community-acquired infections[34].

Cutaneous abscesses in injection drug users are a common presentation in the emergency department. These infections typically occur at injection sites and are caused by a variety of bacterial pathogens, including S. aureus and S. pyogenes[35].

Management

Before initiating treatment, gram staining and bacterial cultures should be taken. The abscess should be incised and drained. Would care and over-the-counter analgesia can help with pain following incision. The antibiotic therapy will depend on the results of the bacterial culture[36].

Necrotising fasciitis

ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Necrotising fasciitis is a rare but severe infection that affects the deeper layers of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, including the fascial planes. It is characterised by severe pain, erythema, swelling and systemic toxicity. The affected area may have a tense, shiny appearance with a dusky or violaceous discolouration. Immediate surgical intervention and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics are necessary[1].

Management

Management involves urgent hospital admission as it is considered a medical emergency. Surgery will remove the affected tissue and the wound will need to be managed with good wound care measures, such as washing with saline and dressings. High-dose IV antibiotics should be prescribed[37]. Initial antibiotic therapy should be broad and based on exposure risks. After it can be directed by Gram stain(s) taken at the time of the initial operation. Antibiotics should be continued until operative debridement is no longer needed (i.e. when no more dead tissue needs to be surgically removed) and the patient is afebrile and hemodynamically stable[37]. The duration of antibiotics should be tailored on an individual basis. Patients will require aggressive fluid resuscitation[38]. This is because of haemodynamic instability; therefore, nutritional and fluid support is needed to replace proteins and fluid owing to the significant wounds and surgical demands. The metabolic demands on the body are significant and therefore the patient has twice the basic caloric requirement[37].

Initial antibiotic treatment should include:

- Piperacillin-tazobactam IV 4.5g eight-hourly plus clindamycin IV 1.2g six-hourly;

- Add vancomycin IV as per protocol if MRSA positive (any site)[39,40].

Pyomyositis

Reused from Akhaddar [40]

[41]

Pyomyositis is a bacterial infection that affects skeletal muscles. It presents as a painful, indurated and erythematous mass with systemic symptoms, such as fever and leukocytosis. It is more common in tropical regions and is commonly caused by S. aureus[42].

Management

Imaging of the affected area is recommended with MRI and drainage of the purulent site of infection is needed. Blood cultures should be performed, and testing of the purulent material is required[43].

Vancomycin is the recommended therapy; dosing is based on weight, for example 15–20 mg/kg every 8–12 hours (maximum per dose 2g), adjusted according to plasma-concentration monitoring[19]. However, if culture results show that the infection is caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, the preferred antimicrobial therapy is with cefazolin, nafcillin or oxacillin[44].

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY (left) and ANDY CRUMP/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY (right)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by Leishmania species. It presents as ulcerative skin lesions with raised borders, which may be painless or associated with mild itching. The presentation of the lesions can vary depending on the specific Leishmania species and the host immune response. For example, in many species the lesion can heal spontaneously with scarring, and in some others, the lesion may heal with scarring but reappear elsewhere alongside the line of lymphatic vessels[45,46].

Management

Treatment is typically under specialist care involving intralesional injections of sodium stibogluconate. Effectiveness of treatment will depend on the infecting leishmanial species[47].

Localised treatment for management includes topical paromomycin (15%) and methylbenzethonium chloride (12%) in soft white paraffin (ointment), thermotherapy, cryotherapy and photodynamic therapy[47].

If considering cryotherapy, then hypopigmentation following cryotherapy is more prominent, frequent, and long-lasting in people of colour. These side effects need to be explained if considering this treatment in this patient group[48].

Conclusion

Skin and soft tissue infections remain a significant healthcare challenge owing to their varied risk factors and presentations. Understanding these factors is crucial for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and implementation of preventive measures. Pharmacists should remain vigilant, considering the changing landscape of pathogens to ensure any identified cases are signposted in a timely manner.

-

1

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Executive Summary: Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;59:147–59. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444 -

2

ELLIS SIMONSEN SM, VAN ORMAN ER, HATCH BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005;134:293–9. doi:10.1017/s095026880500484x -

3

Lopez FA, Sanders CV. DERMATOLOGIC INFECTIONS IN THE IMMUNOCOMPROMISED (Non-HIV) HOST. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2001;15:671–702. doi:10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70164-1 -

5

Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infectionsa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;54:e132–73. doi:10.1093/cid/cis346 -

6

Rybak MJ, Hershberger E, Moldovan T, et al. In Vitro Activities of Daptomycin, Vancomycin, Linezolid, and Quinupristin-Dalfopristin against Staphylococci and Enterococci, Including Vancomycin- Intermediate and -Resistant Strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1062–6. doi:10.1128/aac.44.4.1062-1066.2000 -

7

Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Rieg G, et al. Necrotizing Fasciitis Caused by Community-Associated Methicillin-ResistantStaphylococcus aureusin Los Angeles. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1445–53. doi:10.1056/nejmoa042683 -

10

Silverberg B. A Structured Approach to Skin and Soft Tissue Infections (SSTIs) in an Ambulatory Setting. Clinics and Practice. 2021;11:65–74. doi:10.3390/clinpract11010011 -

11

Rajan S. Skin and soft-tissue infections: Classifying and treating a spectrum. CCJM. 2012;79:57–66. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11044 -

12

Marwick C, Broomhall J, McCowan C, et al. Severity assessment of skin and soft tissue infections: cohort study of management and outcomes for hospitalized patients. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010;66:387–97. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq362 -

13

Ansari F, Erntell M, Goossens H, et al. The European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) Point‐Prevalence Survey of Antibacterial Use in 20 European Hospitals in 2006. CLIN INFECT DIS. 2009;49:1496–504. doi:10.1086/644617 -

14

Burnham JP, Kirby JP, Kollef MH. Diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections in the intensive care unit: a review. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1899–911. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4576-0 -

15

Koning S, van der Wouden JC, Chosidow O, et al. Efficacy and safety of retapamulin ointment as treatment of impetigo: randomized double-blind multicentre placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1077–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08485.x -

16

Kaplan S. Impetigo, ecthyma, and other superficial skin infections. In: Feigin R, Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison G, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Saunders 2018. 1242–1247.

-

17

Esposito S, Bassetti M, Concia E, et al. Diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTI). A literature review and consensus statement: an update. Journal of Chemotherapy. 2017;29:197–214. doi:10.1080/1120009x.2017.1311398 -

22

Cunha BA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: clinical manifestations and antimicrobial therapy. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2005;11:33–42. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01162.x -

30

Bayonne-Kombo ES, Voumbo-Mavoungou Y, et al. Facial Cellulitis and Erysipelas with Cutaneous Portal of Entry: Five Cases in Brazzaville, Congo. Global J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019;7:1–5. doi:10.12970/2310-998x.2019.07.01 -

33

Eriksson B, Jorup-Ronstrom C, Karkkonen K, et al. Erysipelas: Clinical and Bacteriologic Spectrum and Serological Aspects. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;23:1091–8. doi:10.1093/clinids/23.5.1091 -

34

Pallin DJ, Binder WD, Allen MB, et al. Clinical Trial: Comparative Effectiveness of Cephalexin Plus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Versus Cephalexin Alone for Treatment of Uncomplicated Cellulitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;56:1754–62. doi:10.1093/cid/cit122 -

35

Lamagni TL, Neal S, Keshishian C, et al. Epidemic of severe Streptococcus pyogenes infections in injecting drug users in the UK, 2003–2004. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2008;14:1002–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02076.x -

37

Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, et al. Current Concepts in the Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis. Front. Surg. 2014;1. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2014.00036 -

40

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41:1373–406. doi:10.1086/497143 -

42

Radcliffe C, Gisriel S, Niu Y, et al. Pyomyositis and Infectious Myositis: A Comprehensive, Single-Center Retrospective Study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8:ofab098. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab098 -

43

Sethi A. Bacterial Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in the Tropics. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease. 2013;:515–8. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-4390-4.00232-0 -

45

Reithinger R, Dujardin J-C, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007;7:581–96. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(07)70209-8 -

46

Bilgic-Temel A, Murrell DF, Uzun S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: A neglected disfiguring disease for women. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 2019;5:158–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.01.002