Blood

Donated blood is kept free from pathogens

HERSHEY — When a patient needs a blood transfusion, they often don’t have time to consider the source. During emergencies, they just want it to be safe and available. Blood banks work hard every day behind the scenes to make sure their supplies of the invaluable crimson liquid continue to flow. That can mean soliciting donations during lean times and monitoring to ensure that ample supplies of critical blood types are coming in when stocks start to dwindle.

But more than anything, phlebotomists and other blood transfusion professionals take constant precautions to make sure their stockpiles are free from anything harmful. A battery of tests for blood-borne illnesses is performed on every donation, and other methods to purify samples — such as pathogen reduction — are geared to further prevent transfusion-transmissible illness.

Still, with the pandemic still fresh in everyone’s mind, some patients have questions and concerns about these long-tested, tried and true practices. Just how safe is it? Dr. Melissa George, medical director of transfusion medicine at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, discusses blood transfusions, how they’re safeguarded, what can enter your body through a donation — and what can’t.

Left unchecked, what kinds of illnesses can be transferred by blood transfusion?

A few examples, according to George, are:

—Hepatitis B and C

—Human immuno deficiency virus (HIV)

—Human T-lymphotropic virus types

—Syphilis

—West Nile virus

—Other illnesses depending on factors like the region where the donor lives

Primarily, these are illnesses of the blood, and blood banks use highly sensitive and sophisticated tests for all of them, George said. Respiratory illnesses like the common cold and COVID-19 do not infect someone through a blood transfusion.

New tests are added or subtracted when necessary. For example, a few years ago during the Zika virus epidemic in the U.S., blood banks rapidly began testing for the illness to safeguard supplies. They found the number of cases was so small that they discontinued the practice, said George.

“The blood donation community is very much on top of these things,” George said. “We use the latest science to keep our blood supply safe.”

What are the odds of one of these illnesses getting through?

“Very slim,” George said. The odds of contracting HIV from a transfusion is estimated to be one in 1.5 million; hepatitis B, one in 1 million; and hepatitis C, one in 1.2 million. A person’s odds of being struck by lightning at some point in their lifetime are one in 15,300.

What about vaccines? Say I’ve elected not to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. If I receive blood from someone who has been vaccinated, won’t I be vaccinated as well?

No. The vaccine can’t be transferred through a donation, said George, adding that, in fact, labs don’t test for the vaccine in donated blood because the transference just isn’t possible.

When someone receives a vaccine, their blood develops antibodies that can protect them from future severe complications from that virus — and those can be transmitted between donor and recipient. But when it comes to respiratory illnesses like COVID-19, the antibodies that are transmitted through blood products usually don’t work for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

Case-in-point: Early in the pandemic, as doctors sought treatments to fight the illness, doctors attempted to use convalescent plasma — a blood product from a recently infected person — to fight the disease in an infected person. It was determined to be largely ineffective, explained George.

What if I want to line up a directed donor ― someone I know or to whom I am related who will donate the blood I’ll use? Won’t that be safer?

George and others have received an increasing number of requests from people seeking to schedule friends or family member to donate blood specifically for them, George said. Often, their concerns are born out of worries about receiving COVID-vaccinated blood.

“In general, it’s something the blood donor community discourages because it’s actually been shown to be less safe,” George said. While the donor might be known to the recipient, often their risk factors are not.

“They may have risk factors for hepatitis C or sexual behaviors that they don’t want their family to know about,” George said. “The potential donor cannot be collected if they disclose a factor that would make them ineligible to donate, and blood can’t be used if the donor tests positive for a transfusion-transmissible illness. There is also a chance of confidentiality being broken if the potential recipient realizes that their directed donor was unable to donate. This can cause awkward interpersonal interactions and undue pressure on the potential donor, who may feel compelled not to disclose risk factors.”

Meanwhile, the hospital’s general supply of blood has been checked and rechecked and is known to be safe, said George.

How do you determine someone is an eligible donor?

Before they give blood, a donor first answers a series of questions, both written and verbal. These questions will probe a number of risk factors, such as sexual behavior, tattoos, use of needles and travel history. The queries are made in private screening rooms and kept confidential.

“The goal is to protect the donor’s confidentiality and make them feel safe and comfortable in the donation process,” George said.

How do you test the blood?

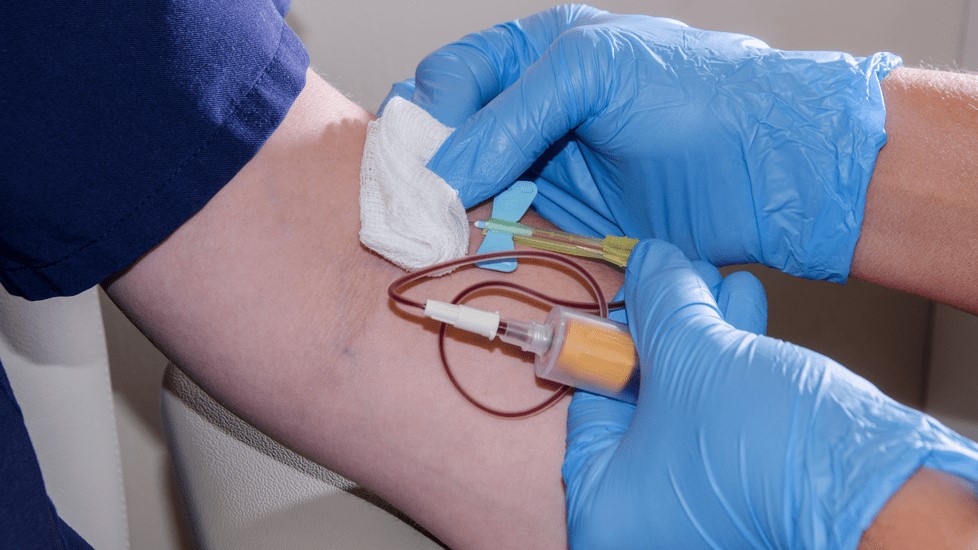

When the donation is made, a small volume of blood is collected for infectious-disease testing. Blood donation centers or suppliers perform the tests, either on their own or through contracts with a lab.

What other methods are there for protecting supplies?

Platelets, the cell fragments in blood that create the clots the body needs to stanch bleeding, aren’t refrigerated and must be kept at room temperature in incubators. Blood banks often put them through a pathogen reduction process that kills many different types of viruses, bacteria and parasites.