Infection

Leprosy May Be Endemic in Central Florida, Scientists Report

The News

Leprosy, a fearsome scourge of ancient civilizations, may have become a permanent fixture in Florida, according to a new study.

The authors described a 54-year-old man who was diagnosed with the illness but had no known risk factors and had never traveled outside Florida. Other people have similarly become infected without obvious explanation, suggesting that leprosy is now endemic in the state, the researchers said.

Their report appeared in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Still, there is no rising tide of leprosy in Florida. In the United States, the number of infections plummeted after peaking in 1983 but began a slow rise again about 20 years ago. The number of cases in the United States is fewer than 200 each year, and it is not rising.

“It’s a drop in the bucket, especially when you view it through a global lens,” said Dr. Charles Dunn, a dermatologist and an author of the study.

“Our paper simply highlights that there appears to be this really intriguingly strong geographic predilection for this illness that’s very uncommon,” he added.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “does not believe there is a great concern to the American public,” a spokeswoman said in an email. The number of cases “is very small.”

Why It Matters: The disease can be treated if doctors recognize it.

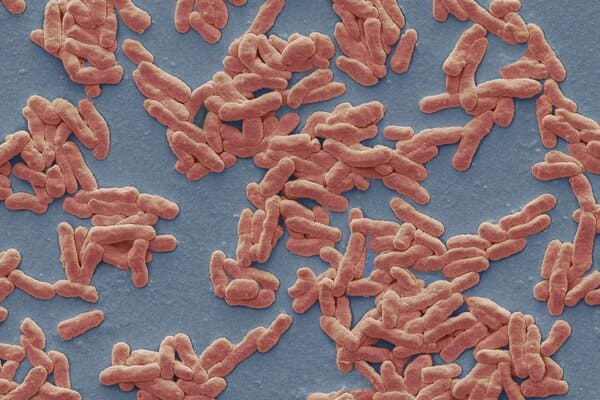

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is caused by slow-growing bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. About 95 percent of people are genetically resistant to the bacteria.

There were 159 new cases in 2020, the most recent year for which national data are available. New cases are reported most commonly in Florida, California, Louisiana, Hawaii, New York and Texas. Central Florida accounts for 81 percent of the cases reported in that state.

The bacteria are thought to be transmitted by droplets from the nose and mouth of an infected patient, but only after close, sustained contact. Armadillos famously carry the bacteria, and people may become infected through contact with the animals.

Caught early enough, leprosy can be cured with standard antibiotic drugs taken over a year. Treatment can make patients noninfectious within a week.

But, left untreated, the bacteria can damage nerves and lead to permanent disabilities including paralysis and blindness. The physical changes associated with the disease can also lead to the enduring stigmatization and isolation of infected people.

“The fact that this patient had never traveled outside of the state of Florida was something that we just wanted to bring to light to those clinicians and physicians that are in the area,” said Dr. Rajiv Nathoo, a dermatologist and senior author on the study.

What It Looks Like: Striking symptoms can take decades to develop.

M. leprae may damage skin, peripheral nerves, the upper respiratory tract and the eyes.

The disease starts with either discolored, numb patches on the skin or with tiny nodules under it. Early symptoms can easily be mistaken for other skin conditions like psoriasis or eczema. Symptoms can develop as many as 20 years after exposure, making it even more challenging to diagnose the disease.

Left untreated, the bacteria slowly destroy nerves and muscles, leading to striking deformities in the hands and feet, sometimes referred to as claw hands and hammer toes.

The disease was first described thousands of years ago. While it may seem like a thing of the past, roughly 200,000 new infections continue to crop up all over the world each year, with a majority in Southeast Asia and India, according to the World Health Organization.

Eliminating the disease in some countries like India has proved to be much more challenging than public health officials expected.

What Scientists Don’t Know: How some cases are acquired.

Researchers have identified a second type of bacteria that leads to leprosy. Both pathogens are close cousins of the bacteria that cause tuberculosis.

None of these bacterial species can easily be cultured in the lab, leaving many questions unanswered about the disease’s transmission and progression.

New cases of leprosy were often diagnosed in people who had traveled to other parts of the world. But since 2015, more than one-third of the cases in the United States have been locally acquired.

Many new patients report no travel or contact with armadillos that would explain their infection, according to the researchers.