Cancer and neoplasms

Baltic Sea pollution puts fish cancer defenses to the test

Cancer can affect all organisms, but species vary in their resistance to this disease.

Due to the fact that larger body size and longer lifespan increase the likelihood of cancer, species with larger bodies and longer lifespans have evolved more robust cancer defense mechanisms. For example, the risk of dying because of cancer is 17 percent in humans, but only 5 percent in elephants.

Humans and other animals are more susceptible to cancer due to pollution. Since pollution spreads rapidly through water and accumulates for extended periods of time in sediments, aquatic animals are especially vulnerable to cancer-causing pollution.

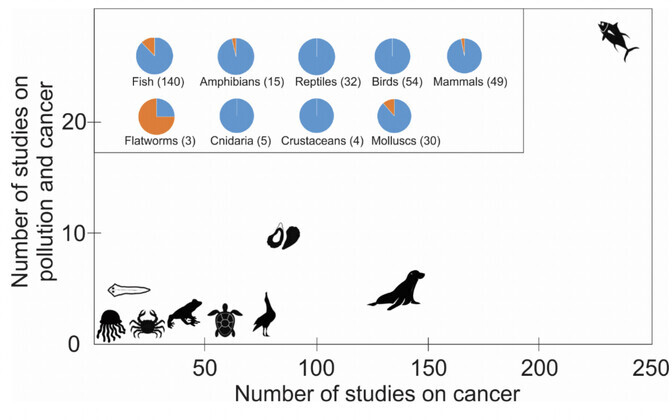

Ciara Baines, a marine biologist at the University of Tartu, studied the links between pollution and cancer in aquatic species. At least 300 species of fish are known so far to have cancer, she said, explaing that fish usually develop tumors on their epidermis, gills and liver.

However, she went on to say, the majority of scientifically described fish species have not been examined from this perspective. Even less is known about the relationship between cancer and environmental pollution. “Only about 30 species have been linked to an increase in cancer due to pollution. So there are still significant gaps in our understanding,” she said.

There have been rounds of research into the effects of pollution on the development of cancer. The last time the topic was more prevalent was in the 1980s. Since then, the incidence of fish cancer has been regarded as a measure of the region’s overall purity. “Especially the bottom dwelling species are at risk,” she added.

In recent years, again, there has been a resurgence of interest in the field among researchers. “In the future the number of studies on this topic will almost certainly increase due to the affordable cost of genetic technology.” So the ability to sequence the genetic material of fish at a lower cost and to examine the expression of different genes helps to better understand the capacity of species to adapt to various noxious compounds.

Two species of flatfish were studied in the Baltic and the North Sea — the two most polluted seas — in order to figure out the link between cancer defences and pollution

Baines comparative study of two species living in the bottom of the Baltic and North seas, flounder and dab, allowed to predict which fish species have the strongest and which have the weakest genetic defenses against cancer.

Although it is important to investigating the effects of chemicals in the lab, she said, it will never replicate what could be observed in the wild, in the natural habitat of the species. “Fish are never exposed only to a single toxin. Hundreds, if not thousands, of hazardous chemicals are floating around in their environment and this is exacerbated by additional factors, such as differences in salinity, temperature and the risk of falling prey to predators, all of which ultimately influence natural selection,” Baines went on to explain.

The researcher undertook on a field study of two flatfish species to explore whether gene expression and oxidative DNA damage levels could explain differences in cancer prevalence’s in fish from polluted vs clean sites: to investigate whether fish living in polluted areas could indeed adapt to reduce their cancer risk. In short, she asked why one of them is more vulnerable to cancer than the other.

Baines looked at two of the most polluted seas in the world — the Baltic and the North Sea. These marine areas are heavily polluted due to the release of high levels of known oncogenic contaminants since the beginning of the industrial revolution. So the researcher said that these polluted environments could be seen as “natural laboratories” to understand the interactions between the evolution of cancer defenses and pollution.

“Unfortunately, the Baltic Sea is one of the most polluted seas in the world, but these are good places to study pollution-related cancers. Also salinity has a strong impact on the health of organisms, comparing this factor was particularly interesting,” said the marine ecologist.

The evolution of cancer-fighting defense mechanisms is unpredictable

European flounder (Platichthys flesus L.) and dab (Limanda limanda L.) inhabit both a relatively clean areas and severely polluted habitats in the Baltic and North Seas.

Baines found that that there are differences in adaptations mechanism that develop in their populations living in more polluted areas and help them to better cope with the cancer-promoting effects of pollution.

For cancer to occur in flounder, many genes need to be suppressed, while the same is not seen in dabs. This suggests that flounders have defense mechanisms against cancer that are not present in dab.

Although both European flounders and dabs showed susceptibility to cancerous skin and liver lesions, the evidence suggests that dabs have almost

10 times higher prevalence of liver neoplasms than European flounders. Moreover, flounders living in highly polluted sites do not seem to have higher cancer prevalence compared to their conspecifics in cleaner sites. Whereas in dabs, cancer prevalence does vary relative to local pollution levels. “Investigating the links between pollution and cancer is therefore probably more meaningful if we make cross-species comparisons rather than only just looking at individuals of the same species in different places,” Baines said.

This suggests that there are differences in cancer defenses both when comparing flounders and dabs, but also within the species, dependent on whether a population is living in a heavily polluted area or not. In other words, certain cancer defense mechanisms have indeed emerged in one of the examined species, the European flounder.

Baines suggested that exploring these potential differences in cancer defenses in wild organisms could help to predict cancer dynamic in our changing environments, and whether a species has adapted to cope with pollution-induced cancer.

There is no link between pollution-induced free radicals and the DNA damage they cause, and the presence or absence of cancer

Baines also tried to shed light on the mechanism by which pollution actually causes cancer. Free radicals generated in the body by pollutants are thought to play a key role. These, in turn, break down DNA and cause different mutations. “However, I did not see in my work that the amount of DNA damage could have been used as a predictor of whether or not the lesions examined had cancer,” the marine ecologist said.

The researcher suggested that mechanisms other than oxidative damage play a more significant role in determining the likelihood of cancer in these two species.

Genes suppressing cancer develop at expense of other evolutionary needs

Additionally, more DNA damage was found in older and larger fish. The genetic material of Baltic flounder was also more damaged than that of their North Sea relatives. Baines suggested that fish who live longer and grow larger have to compensate the number of copies of genes allowing them to grow large with additional copies of genes suppressing cancer.

Taken as a whole, the results of the thesis suggest that more attention needs to be paid to long-term effects when setting pollution limits. Diseases such as cancer do not occur overnight. “Much also depends on the exact cocktail of chemicals that fish are exposed to on a daily basis. Different compounds can both amplify and diminish each other’s effects.”

“One thing is for sure, the cleaner the environment, the less pressure on fish. Yes, some organisms may be able to adapt to pollution over longer periods of time, but the energy spent on these adaptations could be used much more wisely elsewhere,” Baines said.

Check out the thesis in the University of Tartu digital collection. Baines was supervised by Tuul Sepp and Lauri Saks from the University of Tartu and Mathieu Giraudeau from the University of La Rochelle. The supervisor was Joachim Sturve from the University of Gothenburg.

—

Follow ERR News on Facebook and Twitter and never miss an update!