Infection

Scientists Discover a Genetic Variant That Seems to Limit HIV Infection

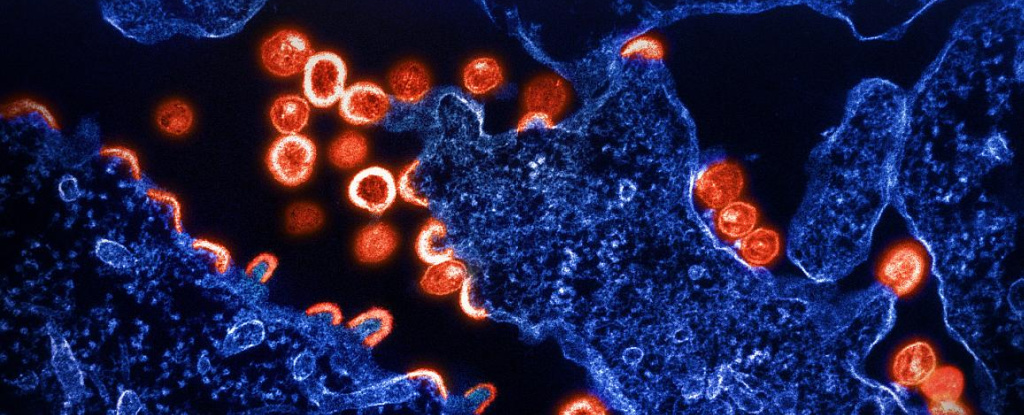

A tiny fraction of people are naturally resistant to HIV infections, and scientists want to understand why.

Now an international team of researchers has discovered a new genetic variant in people of African ancestries that appears to restrict HIV replication after an infection sets in.

Though more research is needed to confirm their findings, the discovery is a huge step forward for HIV research, which has long neglected African populations.

“The findings may explain why certain people in these populations have a lower viral load, which slows down the virus from replicating and transmitting,” says pathologist and study author Simon Mallal from Murdoch University in Perth, Australia.

The discovery, from a combined analysis of nearly 3,900 individuals, could also pave the way to developing new antiviral drugs as previously identified genetic variants have done in the past.

Today HIV affects around 39 million people worldwide, though it’s clear the virus doesn’t affect everybody in the same way. But aside from genetic flukes in one gene called CCR5, the other known genetic variants thought to confer some resistance to HIV have not always stood up to scrutiny when scientists tried to replicate results.

What’s more, genetic studies have mainly been conducted in Caucasian populations of European descent, while most infections occur in Africa, overwhelmingly affecting people of African ancestry.

Researchers have more recently begun studying African populations. In 2021 genetic variants were uncovered in Botswana that appear to either make people more susceptible to HIV infections or drive disease progression.

In this new study of African people living with HIV-1 – the most common type of the virus – researchers found the opposite: a collection of 16 genetic variants that seems to limit HIV replication.

The variants clustered around a gene on chromosome 1 called CHD1L. One particular genetic substitution topped the list of variants associated with low levels of the virus at the most chronic period of infection.

That’s good news because this level, known as a set-point viral load, is an indicator of transmission risk and the likelihood of disease progression in chronic HIV infections.

“By studying a large sample of people of African ancestry, we’ve been able to identify a new genetic variant that only exists in this population and which is linked to lower HIV viral loads,” says Paul McLaren, a research scientist at the Canadian National Microbiology Laboratory for HIV genetics.

McLaren and colleagues estimate between 4 and 13 percent of people of African ancestries carry the top-ranking variant in CHD1L.

Although researchers don’t yet know how CHD1L controls viral load, they’re keen to find out because it could lead to new treatment options.

“Every time we discover something new about HIV control, we learn something new about the virus and something new about the cell,” says University of Cambridge virologist Harriet Groom.

Investigating a little further, the researchers found that HIV replication ramped up if CHD1L was switched off in macrophages, a well-known reservoir of HIV-1. Yet there was no effect in T-cells, another type of immune cell, in which HIV usually replicates.

Despite the promising discovery, researchers are well aware that genetic resistance to HIV most likely involves a complex interaction between two or more genetic variants, rather than one exceptional quirk.

It also remains unclear just how much genetics contributes to the variability in HIV infections.

Systemic and social factors, such as racial inequities and access to treatment, also impact which groups are more likely to be diagnosed with HIV, how quickly HIV progresses to AIDS, or whether the virus is controlled at levels below what can be transmitted to other people.

The study has been published in Nature.