Infection

Where Do We Draw the Line? Duration of Antibiotic Therapy Varies for Bloodstream Infections

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are some of the leading causes of mortality from infection worldwide.1 Mortality rates may increase further with delays in initiation of antimicrobial therapy, which makes reduction in broad-spectrum antibiotic use in the initial empiric phase of treatment challenging.2 However, excessive duration of antibiotic treatment poses challenges and is associated with adverse drug events, high costs, and increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.3 The rise in antimicrobial resistance has become a global health crisis. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens caused more than 2.8 million infections and 35,000 deaths annually from 2012 through 2017.4 Efforts to shorten duration of antibiotic treatment have become paramount in reducing rates of infections with resistant pathogens.

The optimal duration of antibiotic therapy for a primary BSI or BSI secondary to major organ system infections is not clearly defined. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for management of bacteremic scenarios frequently encountered in critical care units—including catheter-related bloodstream infections, intra-abdominal infections, community-acquired pneumonia, pyelonephritis, and skin and soft tissue infections—do not provide firm guidance about the optimal duration of therapy.5-9 Prolonged treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics has been the standard of practice for BSIs. However, there has been a shift toward shorter treatment durations for most patients with a BSI, based on data suggesting that shorter durations may be just as effective. Results of multiple noninferiority trials have shown similar outcomes in patients receiving 7 days versus 14 days of antibiotic treatment for gram-negative bacilli bacteremia.10-12

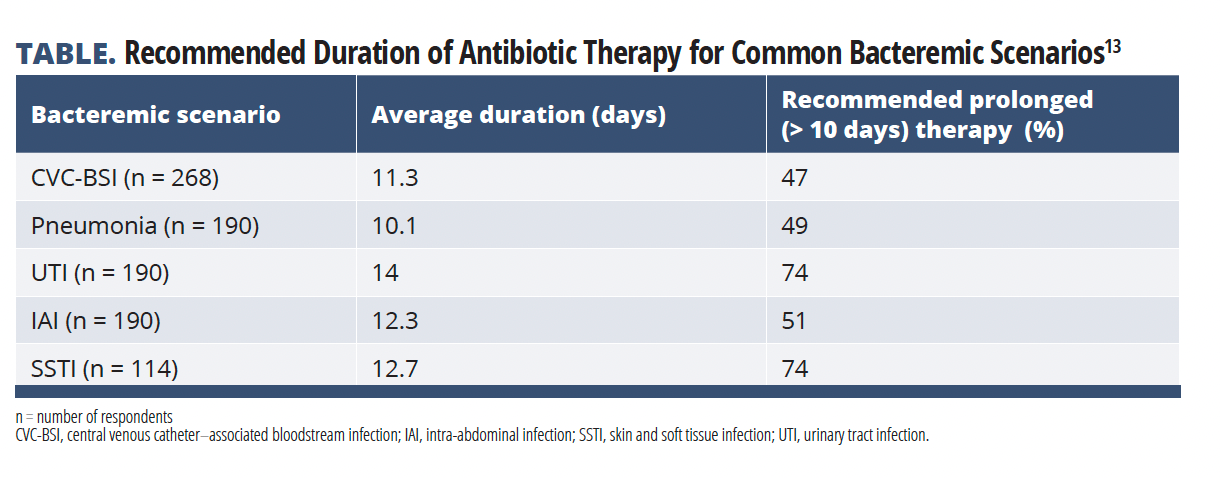

In the absence of high-grade evidence, there is wide variability in the current management of BSIs. Isler et al performed an observational study designed to understand treatment duration and timing of oral to intravenous switch of antibiotics for common bacteremic scenarios encountered by infectious disease (ID) and intensive care unit physicians in Turkey (TABLE).13

Data were collected via an online survey distributed from November 2020 to November 2021. The survey, which had 18 questions about 5 common clinical bacteria scenarios, was sent to members of various Turkish ID societies. The duration of antibiotic treatment was applied to the following clinical scenarios: central venous catheter (CVC)-associated bacteremia with Escherichia coli, bacteremic pneumonia with Streptococcus pneumoniae, bacteremic urinary tract infection (UTI) with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, bacteremic skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) with Streptococcus pyogenes, and bacteremic intra-abdominal infection (IAI) with Bacteroides fragilis.13

The primary end point was self-reported duration of antibiotic treatment for bacteremia in patients in critical care who were clinically stable and had achieved adequate source control.

Secondary end points were the effect of patient and pathogen factors on recommended antibiotic duration, length of time before switch from IV to oral antibiotics, and comparison with Australian and Canadian physician practices.

Among the 236 physician responders, the most common recommended antibiotic treatment duration was 14 days (42%), followed by 10 days (27%) and 21 days (8%). The median recommended antibiotic durations were approximately 10 days for CVC-associated bloodstream infections and bacteremic pneumonia, and 14 days for bacteremic urinary tract, intraabdominal, and skin and soft tissue infections. Prolonged therapy, defined as greater than 10 days, was most common for UTI (74%), SSTI (74%), and IAI (51%).

The type of pathogen and resistance patterns further influenced reported antibiotic duration. Most respondents report treating Enterococcus faecalis, E coli, and coagulase-negative staphylococci infections for 10 days. That compares with K pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which most respondents report treating for 14 days. More than half (61%) of respondents reported that they would treat multidrug-resistant organisms/carbapenem-resistant infections for longer than nonresistant bacteria. Host factors also determined choice of antibiotic duration as 90% of respondents stated that patient age younger than 65 years and the presence of diabetes would influence their recommendations during treatment.

Most respondents considered switching patients’ antibiotics from IV to oral, but only after a minimum of 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy. Twenty percent of participants reported they would never switch from IV therapy to oral therapy for the treatment of BSIs. When compared with Australian and Canadian physicians, Turkish physicians on average reported longer antibiotic treatment durations. 74% of Turkish physicians reported prescribing prolonged antibiotic therapy for UTI and SSTI versus only 59% of Canadian physicians and 49% and 34% of Australian physicians for UTI and SSTI, respectively.13

The authors reported many study limitations, including the study design as a self-reported, voluntary survey, which may have led to recall bias. Study participants were limited to members of ID societies, which may have led to selection bias.

Results of this observational study demonstrate that the current management and duration of antibiotic treatment for bloodstream infections remain highly variable. Despite noninferiority trials demonstrating similar outcomes in patients receiving 7 days versus 14 days of antibiotic therapy for gram-negative bacterial infections, most physicians still report they manage most BSIs with 14 days of antibiotic therapy. Given worsening patterns of emerging antibiotic-resistance, more physicians should consider employing shorter courses of antimicrobial therapy for treatment of critically ill adults with bacteremia.

Highlighted Study: Isler, B, Aslan, AT, Benli, BS, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment and timing of oral switching for bloodstream infections: a survey on the practices of infectious diseases and intensive care physicians. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2023;61(6): 106802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2023.106802

References

1. Verway M, Brown KA, Marchand-Austin A, et al. Prevalence and mortality associated with bloodstream organisms: a population-wide retrospective cohort study. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(4):e0242921. doi:10.1128/jcm.02429-21

2. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589-1596. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9

3. Zuercher P, Moser A, Frey MC, et al. The effect of duration of antimicrobial treatment for bacteremia in critically ill patients on in-hospital mortality – retrospective double center analysis. J Crit Care. 2023;74:154257. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154257

4. Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR-P. aeruginosa). Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(7):e169-e183. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1478

5. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. doi:10.1086/599376

6. Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2010;11(1):79-109. doi:10.1089/sur.2009.9930

7. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27-S72. doi:10.1086/511159

8. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-e120. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257

9. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

10. Molina J, Montero-Mateos E, Praena-Segovia J, et al. Seven-versus 14-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of bloodstream infections by Enterobacterales: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(4):550-557. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.001

11. Yahav D, Franceschini E, Koppel F, et al; Bacteremia Duration Study Group. Seven versus 14 days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(7):1091-1098. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1054

12. von Dach E, Albrich WC, Brunel AS, et al. Effect of C-reactive protein-guided antibiotic treatment duration, 7-day treatment, or 14-day treatment on 30-day clinical failure rate in patients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2160-2169. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6348

13. Isler, B., Aslan, A. T., Benli, B. S., Paterson, D. L., Daneman, N., Fowler, R., & Akova, M. (2023). Duration of antibiotic treatment and timing of oral switching for bloodstream infections: a survey on the practices of infectious diseases and intensive care physicians. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 61(6), 106802.