Infection

The Battle Against the Fungal Apocalypse Is Just Beginning

In February, a dermatologist in New York City contacted the state’s health department about two female patients, ages 28 and 47, who were not related but suffered from the same troubling problem. They had ringworm, a scaly, crusty, disfiguring rash covering large portions of their bodies. Ringworm sounds like a parasite, but it is caused by a fungus—and in both cases, the fungus was a species that had never been recorded in the US. It was also severely drug-resistant, requiring treatment with several types of antifungals for weeks. There was no indication where the patients might have acquired the infections; the older woman had visited Bangladesh the previous summer, but the younger one, who was pregnant and hadn’t traveled, must have picked it up in the city.

That seemed alarming—but in one of the largest and most mobile cities on the planet, weird medical things happen. The state reported the cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the New York doctors and some CDC staff wrote up an account for the CDC’s weekly journal.

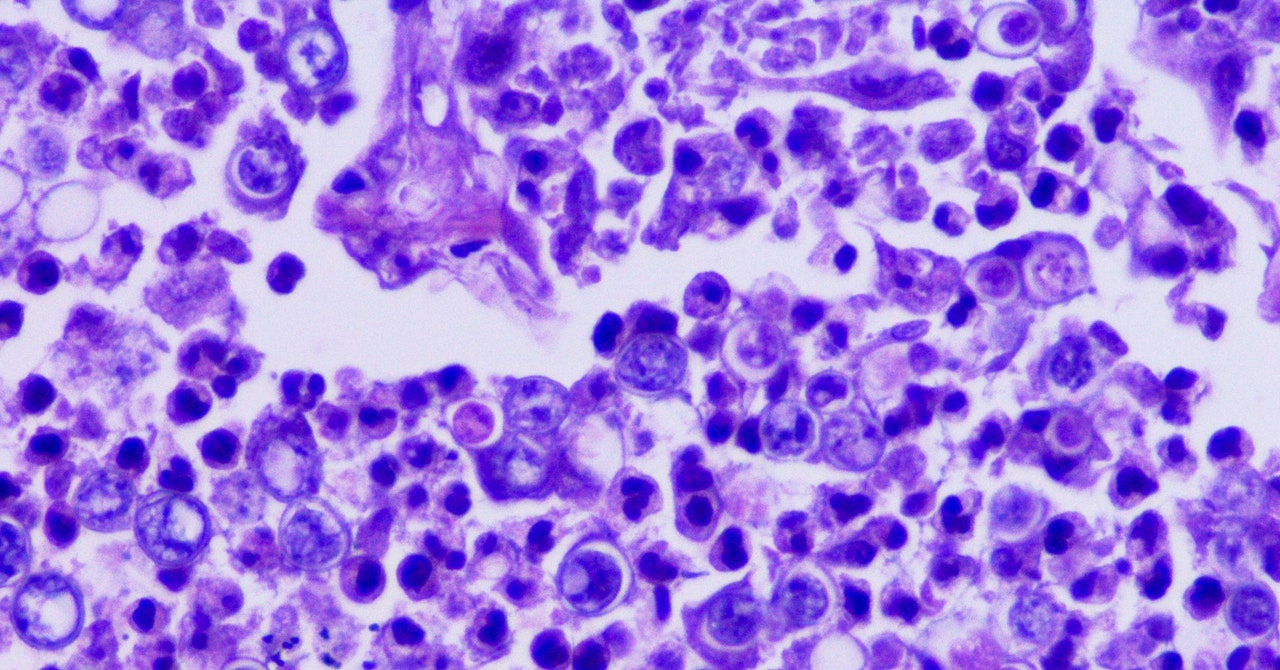

Then, in March, some of those same CDC investigators reported that a fungus they had been tracking—Candida auris, an extremely drug-resistant yeast that invades health care facilities and kills two-thirds of the people infected with it—had risen to more than 10,000 cases since it was identified in the US in 2016, tripling in just two years. In April, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services rushed to investigate cases of a fungal infection called blastomycosis centered on a paper mill, an outbreak that would grow to 118 people, the largest ever recorded. And in May, US and Mexican health authorities jointly rang an alarm over cases of meningitis, caused by the fungus Fusarium solani, which seemed to have spread to more than 150 clinic patients via contaminated anesthesia products. By mid-August, 12 people had died.

All of those outbreaks are different: in size, in pathogen, in location, and the people they affected. But what links them is that they were all caused by fungi—and to the small cadre of researchers who keep track of such things, that is worrisome. The experts share a sense, supported by incomplete data but also backed by hunch, that serious fungal infections are occurring more frequently, affecting more people, and also are becoming harder to treat.

“We don’t have good surveillance for fungal infections,” admits Tom Chiller, an infectious disease physician and chief of the CDC’s mycotic diseases branch. “So it’s hard to give a fully data-driven answer. But the feeling is definitely that there is an increase.”

The question is: Why? There may be multiple answers. More people are living longer with chronic illnesses, and their impaired immune systems make them vulnerable. But the problem isn’t only that fungal illnesses are more frequent; it is also that new pathogens are emerging and existing ones are claiming new territory. When experts try to imagine what could exert such widespread influence, they land on the possibility that the problem is climate change.

Fungi live in the environment; they affect us when they encounter us, but for many, their original homes are vegetation, decaying plant matter, and dirt. “Speculative as it is, it’s entirely possible that if you have an environmental organism with a very specific ecological niche, out there in the world, you only need a very small change in the surface temperature or the air temperature to alter its niche and allow it to proliferate,” says Neil Stone, a physician and fungal infections lead at University College London Hospitals. “And it’s that plausibility, and the lack of any alternative explanation, which makes it believable as a hypothesis.”

For this argument, C. auris is the leading piece of evidence. The rogue yeast was first identified in 2009 in a single patient in Japan, but within just a few years, it bloomed on several continents. Genetic analyses showed the organism had not spread from one continent to others, but emerged simultaneously on each. It also behaved strikingly differently from most yeasts, gaining the abilities to pass from person to person and to thrive on cool inorganic surfaces such as plastic and metal—while collecting an array of resistance factors that protect it from almost all antifungal drugs.

Arturo Casadevall, a physician and chair of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, proposed more than a decade ago that the rise of mammals over dinosaurs was propelled by an inherent protection: Internally, we’re too hot. Most fungi flourish at 30 degrees Celsius or less, while our body temperature hovers between 36 and 37 degrees Celsius. (That’s from 96.8 to the familiar 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit.) So when an asteroid smashed into the Earth 65 million years ago, throwing up a cloud of pulverized vegetation and soil and the fungi those would have contained, the Earth’s dominant reptiles were vulnerable, but early mammals were not.

But Casadevall warned of a corollary possibility: If fungi increased their thermotolerance, learning to live at higher temperatures as the climate warms, mammals could lose that built-in protection—and he proposed that the weird success of C. auris might indicate it is the first fungal pathogen whose adaptation to warmth allowed it to find a new niche.

In the 14 years since it was first spotted, C. auris has invaded health care in dozens of countries. But in that time, other fungal infections have also surged. At the height of the Covid pandemic, India experienced tens of thousands of cases of mucormycosis, commonly called “black fungus,” which ate away at the faces and airways of people made vulnerable by having diabetes or taking steroids. In California, diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis (also called Valley fever) rose 800 percent between 2000 and 2018. And new species are affecting humans for the first time. In 2018, a team of researchers from the US and Canada identified four people, two from each country, who had been infected by a newly identified genus, Emergomyces. Two of the four died. (The fungus got its name because it is “emerging” into the human world.) Subsequently, a multinational team identified five species in that newly-named genus that are causing infections all over the world, most severely in Africa.

Fungi are on the move. Last April, a research group from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis examined the expected geographic range in the US of what are usually called the “endemic fungi,” ones that flourish only within specific areas. Those are Valley fever in the dry Southwestern US; histoplasmosis in the damp Ohio River valley; and blastomycosis, with a range that stretched from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi to New Orleans, and as far east as the Virginia coast. Using Medicare data from more than 45 million seniors who sought health care between 2007 and 2016, the group discovered that the historically documented range of these fungi is wildly out of step with where they are actually causing infections now. Histoplasmosis, they found, had been diagnosed in at least one county in 94 percent of US states; blastomycosis, in 78 percent; and Valley fever in 69 percent.

That represents an extension of range so vast that it challenges the meaning of endemic—to the point that Patrick Mazi, an assistant professor of medicine and first author on the paper, urges clinicians to cease thinking of fungal infections as geographically determined, and focus on symptoms instead. “Let’s acknowledge that everything is dynamic and changing,” he says. “We should recognize that for the sake of our patients.”

Without taking detailed histories from those millions of patients, it can’t be proven where their infections originated. They could have been exposed within the fungi’s historic home ranges and then traveled; one analysis has correlated the occurrence of Valley fever in the upper Midwest with “snowbird” winter migration to the Southwest. But there is plenty of evidence for fungal pathogens moving to new areas, via animals and bats, and on winds and wildfire smoke as well.

However fungi are relocating, they appear to be adapting to their new homes, and changes in temperature and precipitation patterns may be part of that. Ten years ago, CDC and state investigators found people in eastern Washington state infected with Valley fever, and proved they had acquired it not while traveling, but locally—in a place long considered too cold and dry for that fungus to survive. A group based primarily at UC Berkeley has demonstrated that transmission of Valley fever in California is intimately linked to weather there—and that the growing pattern of extreme drought interrupted by erratic precipitation is increasing the disease’s spread. And other researchers have identified cases of a novel blastomycosis in Saskatchewan and Alberta, pushing the map of where that infection occurs further north and west.

The impact of climate change on complex phenomena is notoriously hard to prove—but researchers can now add some evidence to back up their intuition that fungi are adapting. In January, researchers at Duke University reported that when they raised the lab temperatures in which they were growing the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus deneoformans—the cause of a quarter-million cases of meningitis each year—the fungus’s rate of mutation revved into overdrive. That activated mobile elements in the fungus’s genome, known as transposons, allowing them to move around within its DNA and affect how its genes are regulated. The rate of mutation was five times higher in fungi raised at human body temperature than at an incubator temperature of 30 degrees Celsius—and when the investigators infected mice with the transformed fungi, the rate of mutation sped up even more.

Researchers who are paying attention to rising fungal problems make a final point about them: We’re not seeing more cases because we’ve gotten better at finding them. Tests and devices to detect fungi, especially within patients, haven’t undergone a sudden improvement. In fact, achieving better diagnostics was top of a list published by the World Health Organization last fall when it drew up its first ranking of “priority fungal pathogens” in hopes of guiding research.

Multiple studies have shown that patients can wait two to seven weeks to get an accurate diagnosis, even when they are infected with fungi endemic to where they live, which ought to be familiar to local physicians. So understanding that fungi are changing their behavior is really an opportunity to identify how many more people might be in danger than previously thought—and to get out in front of that risk. “Patients are being diagnosed out of traditional areas, and we are missing them,” Mazi says. “All of these are opportunities to achieve better outcomes.”