Infection

Australian study warns over parasitic infections after roundworm found in woman’s brain

Aug. 29 (UPI) — Surgeons in Australia pulled a live 3-inch-long parasitic worm from the front of a woman’s brain in what is believed to be the first time this type of infection has been found in humans.

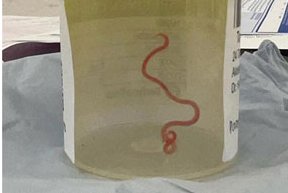

Doctors in Canberra found the light red worm during a biopsy they were carrying out on the patient in a bid to diagnose an unusual set of symptoms including stomach pain, diarrhea, cough, night sweats and cognitive and mental health issues, according to a study published Tuesday in the CDC journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The light red worm pulled from the frontal lobe of the 64-year-old woman’s brain last year turned out to be an Ophidascaris robertsi roundworm which is endemic in carpet python snakes, common across much of Australia.

“Everyone in that operating theatre got the shock of their life when the surgeon took some forceps to pick up an abnormality and the abnormality turned out to be a wriggling, live 8cm light red worm,” Canberra Hospital’s Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake told the BBC.

Senanayake, Associate Professor of Infectious Disease at Australian National University, who was one of the study’s lead researchers, said it was also the first known case to involve the brain “of any mammalian species, human or otherwise.”

“Even if you take away the yuck factor, this is a new infection never documented before in a human being,” he said.

The roundworm’s larvae are usually found in small mammals and marsupials which, when eaten by the python, enable the worm’s life cycle to complete itself inside the snake, Senanayake explained.

The study warns the case may not be the last because other closely related worm species infect snakes elsewhere in the world.

Researchers believe the woman was accidentally infected after preparing food using grasses from around a lake near her home in the southern part of New South Wales inhabited by carpet pythons.

“Despite no direct snake contact, she often collected native vegetation, warrigal greens, from around the lake to use in cooking. We hypothesized that she inadvertently consumed O. robertsi eggs either directly from the vegetation or indirectly by contamination of her hands or kitchen equipment,” the study’s authors wrote.

Invasion of the brain by Ophidascaris larvae had not been reported previously with infection normally limited to the intestine in animal hosts, however, the woman was taking immunosuppressant medication at the time to treat a high white blood cell count which could explain how larvae were able to migrate to her central nervous system.

“The growth of the third-stage larva in the human host is notable, given that previous experimental studies have not demonstrated larval development in domesticated animals, such as sheep, dogs, and cats, and have shown more restricted larval growth in birds and non-native mammals than in native mammals,” the researchers added.

The patient was treated with antiparasitic drugs and six months after surgery to remove the worm, all symptoms had resolved with the exception of her neuropsychiatric issues, which while much improved, persisted.

The study concludes that the case highlights the ongoing risk for zoonotic diseases when humans and animals are in close proximity and warns that while O. robertsi nematodes are only found in Australia, other Ophidascaris species infect snakes elsewhere meaning additional human cases may emerge globally.