Infection

Neurosurgeon plucks live worm from woman’s brain after months of mysteryious symptoms

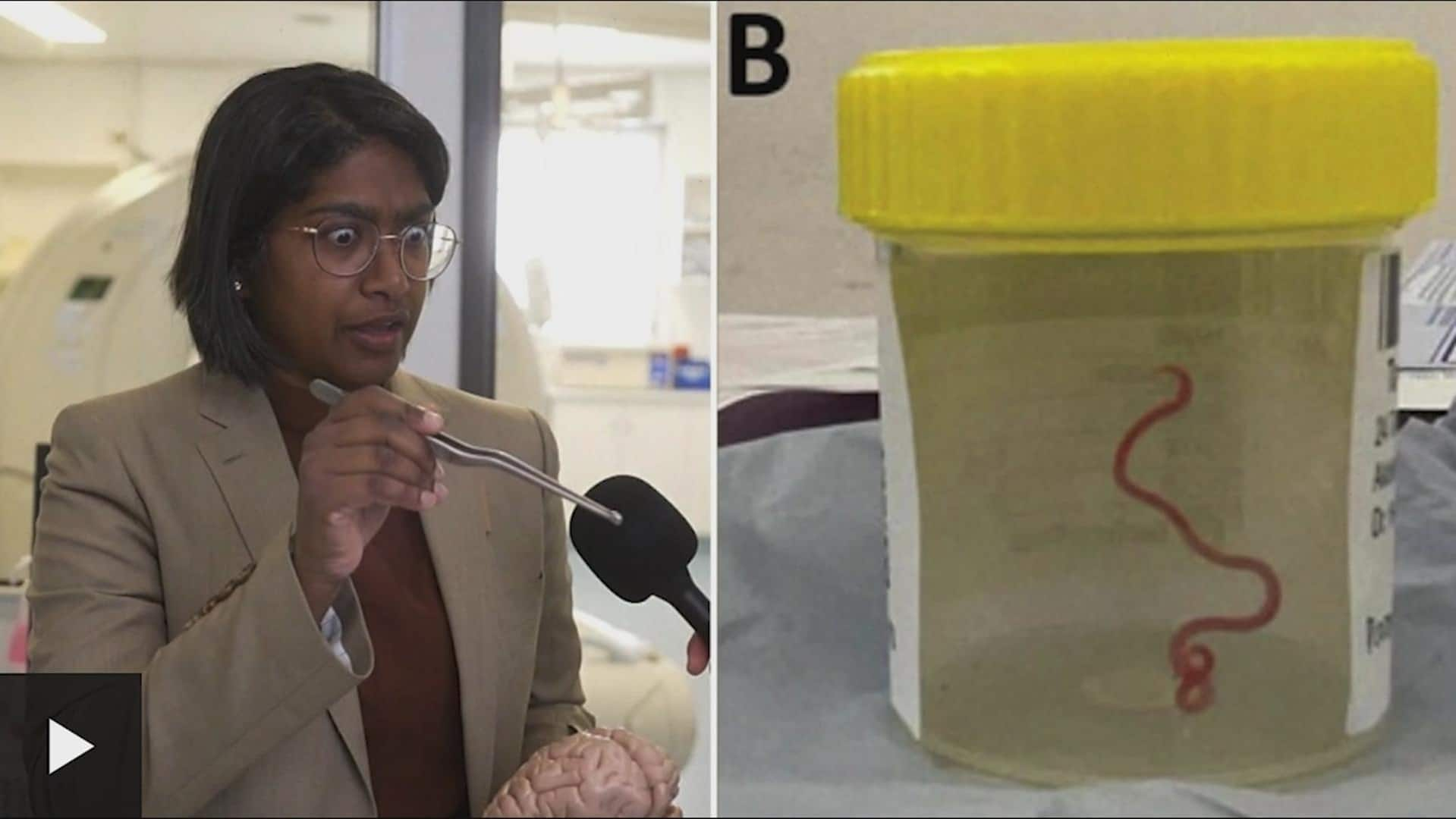

A neurosurgeon investigating a woman’s mysterious symptoms in an Australian hospital says she plucked a wriggling worm from the patient’s brain.

Dr. Hari Priya Bandi was performing a biopsy through a hole in the 64-year-old patient’s skull at Canberra Hospital last year when she used forceps to pull out the parasite, which measured eight centimetres.

“I just thought, ‘What is that? It doesn’t make any sense. But it’s alive and moving,'” Bandi was quoted Tuesday in The Canberra Times newspaper.

“It continued to move with vigour. We all felt a bit sick,” Bandi added of her operating team.

The specimen was the larval form of an Australian native roundworm not previously known to be a human parasite, named Ophidascaris robertsi. The worms are commonly found in carpet pythons.

Doctors describe their shock at the removal of a live, 8-centimetre parasitic worm from a patient’s brain in Australia

Bandi and Canberra infectious diseases physician Sanjaya Senanayake are authors of an article about the extraordinary medical case published in the latest edition of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

According to Senanayake, who said he was on duty at the hospital in June last year when the worm was found, this is the first instance of a parasite like this being found in a human.

“I got a call saying, ‘We’ve got a patient with an infection problem. We’ve just removed a live worm from this patient’s brain,'” Senanayake told Australian Broadcasting Corp.

Changes in her brain

In January 2021, the patient was admitted to her local hospital in southeast New South Wales state after having symptoms like abdominal pain, diarrhea, a dry cough and night sweats, for three weeks.

She was initially treated, but some of her symptoms persisted. Last year, she was again admitted to the hospital after experiencing forgetfulness and worsening depression over three months. Scans showed changes in her brain.

Senanayake said the brain biopsy was expected to reveal a cancer or an abscess.

“This patient had been treated … for what was a mystery illness that we thought ultimately was [an] immunological condition because we hadn’t been able to find a parasite before and then out of nowhere, this big lump appeared in the frontal part of her brain,” Senanayake said.

“Suddenly, with [Bandi’s] forceps, she’s picking up this thing that’s wriggling. She and everyone in that operating theatre were absolutely stunned,” Senanayake added.

The worms’ eggs are commonly shed in snake droppings.

Small mammals then eat the droppings and the life cycle continues as other snakes eat the mammals. The woman lives near a carpet python habitat and often goes there to gather spinach-like vegetation called warrigal greens to cook.

While she had no direct contact with snakes, scientists believe that she consumed the eggs from the vegetation or her contaminated hands.

After the worm was removed, the patient was given other medications to get rid of any other potential larvae that could be growing in her other organs.

Six months post-surgery, the researchers say the woman’s mental symptoms have continued, but improved.

In an interview with Reuters, Senanayake says they continue to monitor the woman’s condition and keep in touch with her.

The Ophidascaris species can infect snakes outside of Australia, so the authors said they assume that “additional human cases may emerge” in other parts of the world.

‘Pretty wild case’

Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease physician in Toronto, said this is a “pretty wild case.”

He said this is a “unique infection” because the person accidentally ingested python feces that had the parasite.

“But in terms of people getting infections through close contact with non-human animals, obviously that’s a big issue and certainly we’re seeing more and more of that,” he told CBC News.

Bogoch said these are specifically called zoonotic infections, which can be viral, bacterial or parasitic.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 75 per cent of emerging diseases in humans start in animals.

Some prominent examples of this, according to Bogoch, are the flu and COVID-19.

“There’s a whole myriad of parasitic infections that are out there, mostly we don’t see a lot of them in Canada,” he said.

Bogoch added that there are some infections people can get locally in Canada and others that people bring into the country from abroad.

“If we’re talking about zoonotic infections, we have to be very concerned about the communicable ones,” he said, adding that those are ones that can transfer between people.

Bogoch said that early detection, early response and surveillance are important to detect these infections and prevent their spread.

With this particular parasitic infection, Bogoch said the woman couldn’t have transferred it to another person, so it’s not something to be concerned about.

“This is a startling infection, but the world does not need to worry about an outbreak of this infection,” he said.

“It’s certainly an impressive case and it’s not every day that a neurosurgical team will pull a live worm out of someone’s brain, but let’s not pretend for a second that there’s a broader public health risk.”

To avoid getting a zoonotic infection, Bogoch said that people should not mistakenly or intentionally consume animal feces, as that’s how diseases can be transmitted.

For people who work with animals or have a pet, Bogoch recommended washing your hands. He also said people eating meat, like pork or beef, should make sure it’s well-cooked.