Infection

COVID infection risk rises the longer you are exposed — even for vaccinated people

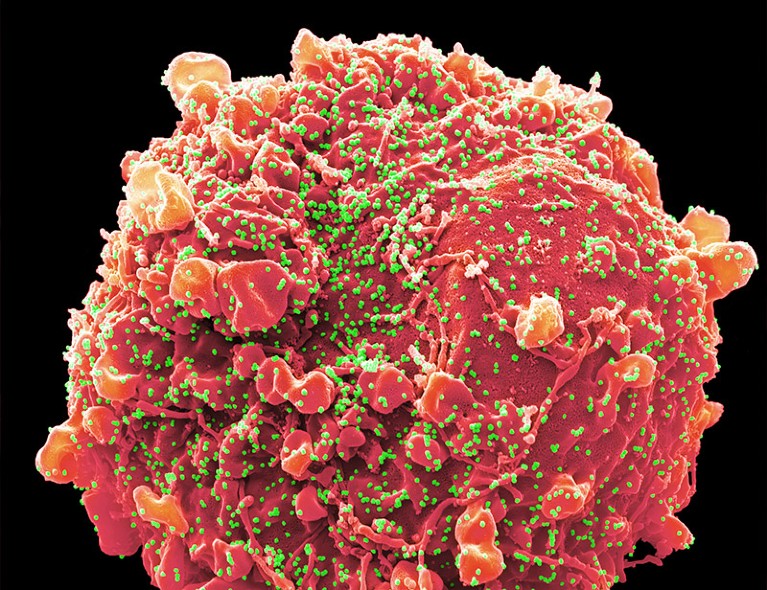

A viral particle (artificially coloured) of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Prolonged exposure in close proximity to someone with COVID-19 puts people at high risk of catching the disease, even if they’ve had both the disease and vaccinations against it, a study1 shows.

The study, published this month in Nature Communications, reveals that the greater a person’s exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the more vulnerable they are to infection, regardless of their vaccination status. This relationship has long been suspected, but the study is one of the first to document it.

The findings point to the importance of masking, improved ventilation and other measures that reduce exposure to the virus, says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not part of the study.

The finding “just makes intuitive sense,” she says. “But now there’s evidence that these [measures] are probably going to be important to help the vaccine-mediated immunity work for you.”

Close contacts

Scientists have speculated since the start of the pandemic that the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection correlates with the amount of virus that a person is exposed to. But verifying this relationship has been difficult because of the challenges in quantifying how much time people spend in close contact with others, and in tracking infections after such contact.

To procure such data, the study’s authors turned to 13 correctional facilities in Connecticut that regularly conducted SARS-CoV-2 tests on residents without symptoms. The researchers assigned ‘close exposure’ status to anyone who shared a cell with an infected person, and ‘moderate’ exposure status to those who shared a cell block but not a cell with an infected resident. Those who lived in separate cell blocks from anyone known to be infected were designated as having no documented exposure.

How much virus does a person with COVID exhale? New research has answers

“The design is very powerful,” says Jose-Luis Jimenez, an aerosol scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “That is the one situation in which you can straight-up control how people move and where people are. That eliminates one of the things that make this type of study difficult.”

The authors’ analysis of more than 10,000 residents and hundreds of SARS-CoV-2 infections found that vaccination, previous infection or both of those protected residents with no documented exposure to the virus, or with only moderate exposure. But neither vaccination, nor previous infection nor the two combined offered significant protection to those with a close exposure, says Margaret Lind, an epidemiologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and a co-author of the study.

Jimenez says that the new study is consistent with his work2 on ‘superspreader’ events, which showed that the duration of exposure to a person with COVID-19 was one of a slew of factors that could predict the chances of catching the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The spread of new viral variants, as well as waning immunity from vaccines or previous infections, also plays a part in understanding a person’s risk of infection.

But many of those factors are outside the control of people weighing their risk of infection, Lind says, whereas masking and avoiding crowded places are “really the adjustable thing, and that gives me some comfort. The next logical step from our findings is that reducing your exposure through these mitigation policies would be helpful.”