Blood

How 2 Mass. doctors helped end discrimination against gay men in blood donation

The morning after the mass shooting at a gay club in Orlando in 2016, Dr. Robbie Goldstein watched the news and cried. He felt compelled to do something, like donate blood — but as a gay man, he wasn’t allowed.

After the Boston Marathon bombing, and during the COVID pandemic, he wanted to donate to help boost the country’s flagging blood supply. Again, he couldn’t.

For decades, federal rules prohibited gay and bisexual men from donating blood, but those rules have finally changed. And this week, for the first time, Goldstein rolled up his shirtsleeve and gave blood, at the Red Cross donation center in Dedham.

“I want to give back, and now finally I can,” he said.

Goldstein, 39, is the Massachusetts commissioner of public health. He is among the experts who urged federal officials to lift the ban on blood donations from men who have sex with men.

The ban began in the 1980s, during the HIV epidemic, as a measure to protect the blood supply. But the rules increasingly were seen as dated and discriminatory, preventing monogamous gay men from giving blood, while taking donations from heterosexual people who have multiple partners and could be at greater risk of HIV.

“We set out to change this policy because we saw it as a policy that had a place in history,” Goldstein said, “but now, it just doesn’t fit with the science.”

Goldstein, an infectious disease physician, worked with colleagues — including his friend and mentor, Dr. Rochelle Walensky — to push for change.

The two worked together at Massachusetts General Hospital, and when Walensky left to lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021, she brought Goldstein on as her senior advisor.

Closer to the seat of power, they advocated for a new blood donation policy, one that accounted for individual risk, without banning large groups of people.

“By the time I was at the CDC, there were people that were starting to work on it within [U.S. Health and Human Services], and we made sure we were at the table so that we could really push this forward at faster speed,” said Walensky, who left the CDC earlier this year.

Donated blood is already tested for diseases, including HIV. In May, officials at the Food and Drug Administration dropped blanket restrictions on who could give blood. They said donors should be screened on their individual risk of HIV, including whether they’ve recently had new sexual partners — not based on their sexual orientation.

The Red Cross, which provides 40% of the country’s blood supply, updated its donation requirements this month.

“You do a lot of work on behalf of the American people, on behalf of the people of Massachusetts, and you don’t necessarily always see it pay off with such a tangible outcome,” Walensky said. “So it was really fulfilling to see this one happen.”

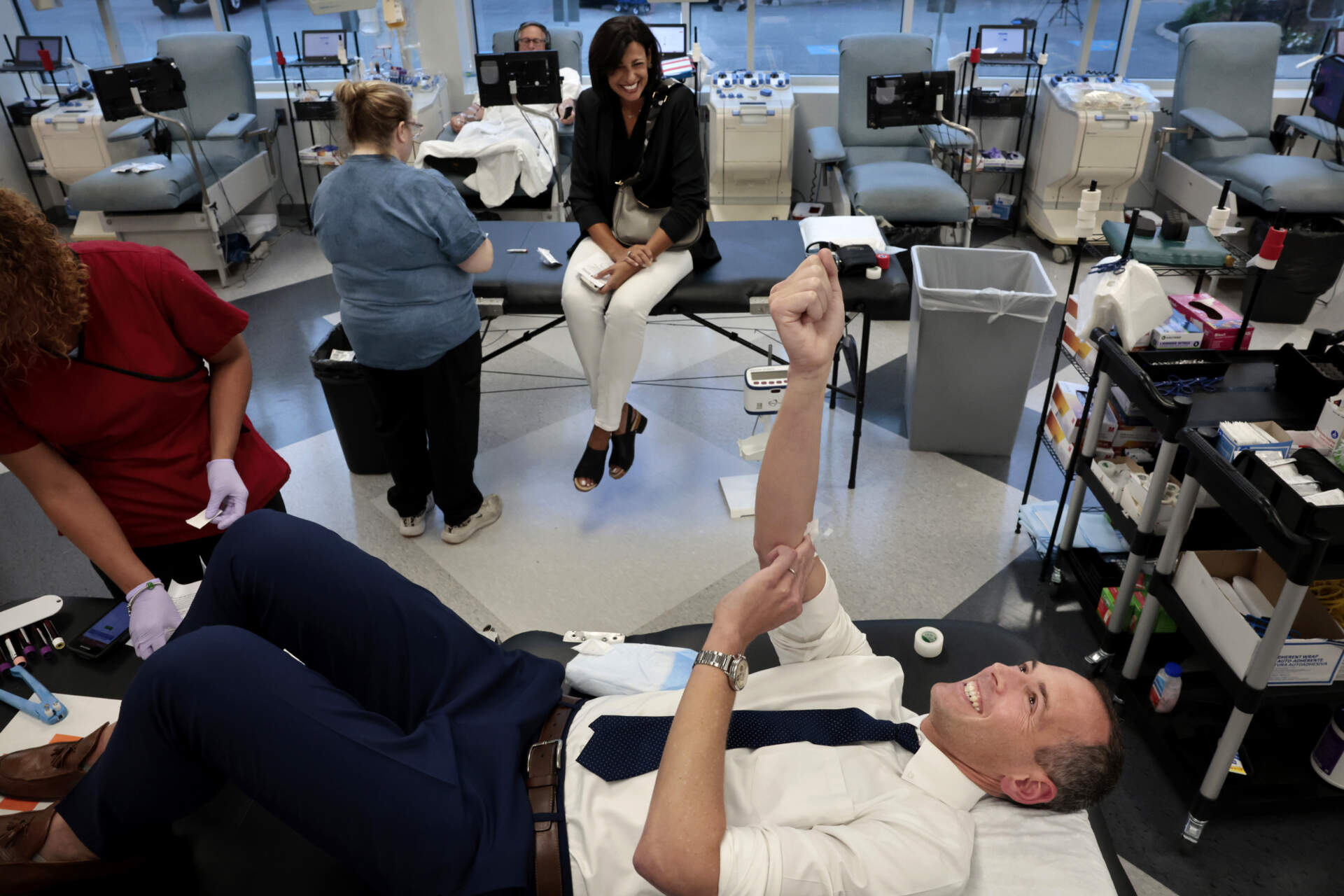

Walensky and Goldstein got together this week and gave blood side by side, keeping a promise they made years ago to donate together once the federal rules finally changed.

“It’s pretty amazing to be here,” Goldstein said. “I didn’t know what to do when I walked in the door because I’ve never walked into an American Red Cross blood donor center before.”

Goldstein said the new guidelines could allow as many as 5 million more people to donate blood. The policy is rooted in evidence, he said, but may need to change again in the future as science advances.

“Policy can take a long time,” Goldstein said. “That is a lesson I’ve learned from this. But if you continue to go back to the science, go back to the data, and you keep pushing, things can happen.”