Infection

How a medical mystery led to a wriggling, parasitic worm in a woman’s brain

A 64-year-old woman in New South Wales, Australia, arrived at a hospital in January 2021 with a confounding set of symptoms. She reported three weeks of abdominal pain, a dry cough and night sweats. Tests revealed lesions in the woman’s lungs, liver and spleen, and an abnormally high white blood cell count.

The high white blood cell count suggested that her body was responding to some kind of infection. But a search for the culprit came up empty. Doctors found no signs of a bacterial or fungal infection and did not detect any parasites. They struggled with a diagnosis for 18 months, while the woman’s symptoms worsened to include forgetfulness and depression.

In June 2022, doctors finally found the source of her ordeal. It was in her brain. And it was alive, wriggling.

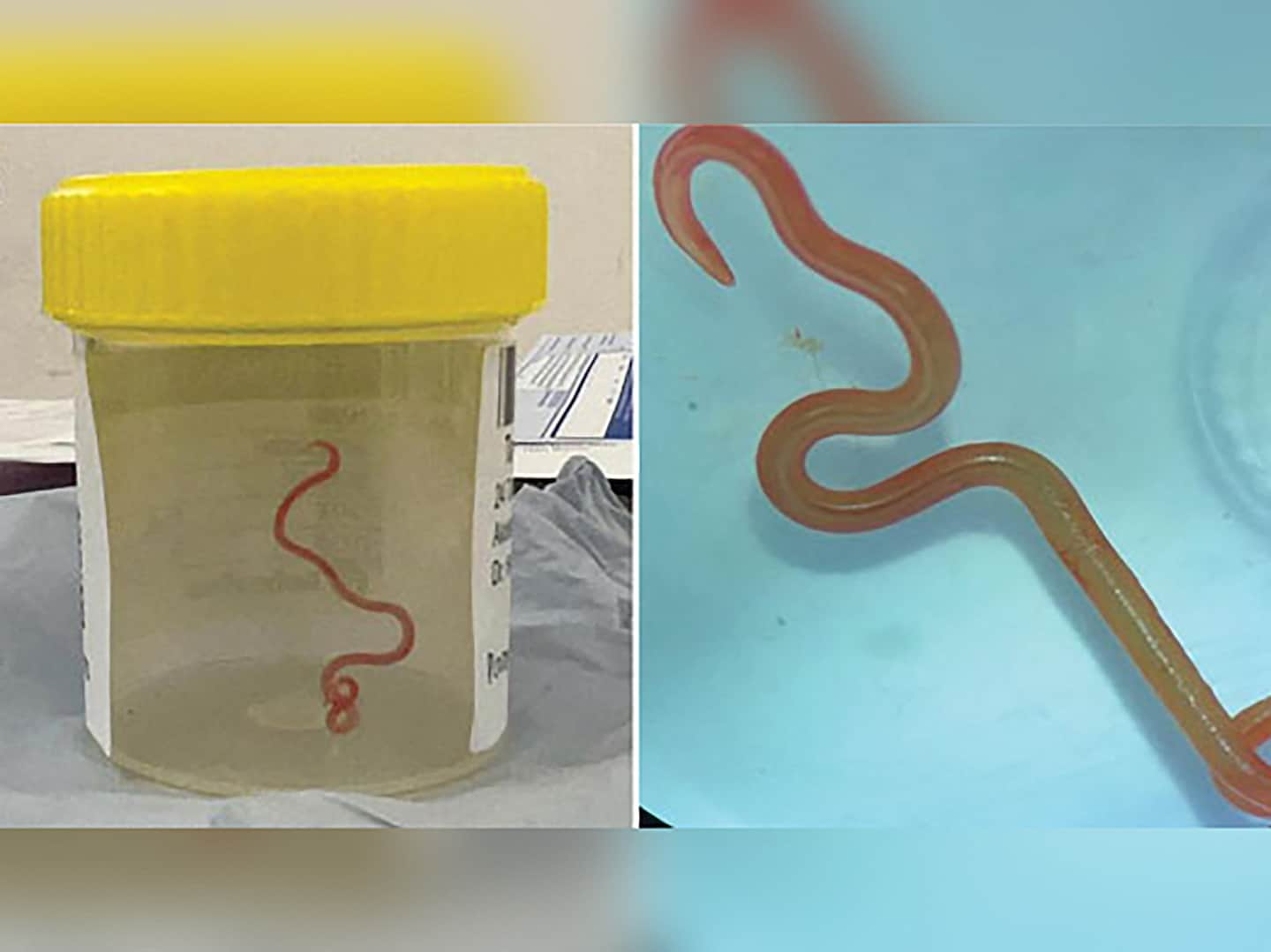

A surgeon at Canberra Hospital extracted a pale red, three-inch-long roundworm from within a lesion in the woman’s brain, in a unique — and stomach-churning — discovery, researchers wrote in early August in Emerging Infectious Diseases, a peer-reviewed journal published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The parasite, a larva of the Ophidascaris robertsi species, had not previously been reported inside a human brain.

“It sounds like a Dr. House episode,” Mehrab Hossain, an infectious-diseases physician at Canberra Hospital, said in an interview with The Washington Post, referring to the TV medical drama “House” (2004-12).

The woman’s shocking experience may have been a case of extraordinarily bad luck, researchers told The Post. While humans can be infected by some types of roundworms, the parasite found in her brain typically resides in the stomachs of carpet pythons, which are common in Australia. The parasite’s eggs are shed into the snakes’ feces and ingested by small mammals like rats, where they grow as larvae before reentering a snake when it eats the mammal.

That life cycle does not involve living inside a human — much less a human brain. But the roundworms are prevalent wherever their hosts are and often find their way into other animals, said Jan Šlapeta, a professor of parasitology at the University of Sydney. Making the jump to a person was unheard of, but not inconceivable.

“It was just a matter of time,” Šlapeta said. “… I’ve seen these worms in all sorts of places, of other animals, and so far the human was just missing.”

The patient, whom the study does not identify by name, lived near a lake inhabited by carpet pythons and collected New Zealand spinach growing around the lake to cook with, according to the study. Researchers speculated that she may have inadvertently consumed O. robertsi eggs either from dirtied vegetation or by contaminating her hands or kitchen equipment.

From there, any roundworm eggs would have followed their usual playbook, releasing larva to burrow into their host’s stomach wall, Šlapeta said. The larva usually stay in a cavity near the stomach, but Šlapeta said the roundworm found inside the woman may have burrowed to other organs in confusion, which would explain the lesions in her liver. Researchers wrote in the study that the roundworm’s survival in the woman’s body may have been aided by the immunosuppressants she was prescribed to treat her high white blood cell levels.

As to how the parasite roamed all the way through her body up to her brain?

“I have no idea,” Šlapeta said.

Doctors suggested an MRI exam of the woman’s brain after she began reporting depression and forgetfulness, according to Hossain, who was part of the team treating her. They detected a lesion in her right frontal lobe. In June 2022, the doctors performed surgery on the woman so they could take a sample of tissue from the lesion.

That was when Hari Priya Bandi, the neurosurgeon who operated on the woman, spotted the worm. It looked out of place within the lesion, red but too pale to be a blood vessel. She grasped it with her surgical instruments.

“She did, until it started moving,” Hossain recounted.

Bandi called Hossain from the operating room to report the unimaginable discovery. It kicked off a chain of inquiries to researchers across Australia, including Šlapeta, who worked together to identify the roundworm’s species and conducted further research on the wayward parasite.

The case drew attention, and not just for its squeamish subject, said Sanjaya Senanayake, an infectious-diseases physician who treated the woman after her surgery. It demonstrated not only the evasiveness of certain parasites and the difficulty in diagnosing their intrusions, but also what Senanayake described as an increasing risk of parasites crossing over to humans as people encroach on their habitats.

“Hopefully, highlighting the possibility of human infection with this parasite might lead to other cases being identified in other parts of the world and other cases being treated as well,” Senanayake said.

With her elusive diagnosis finally in hand, the woman received further medication to flush out potential larvae in other organs, Senanayake said. Her condition has greatly improved since the surgery, according to Senanayake and Hossain. Senanayake praised his patient for keeping her spirits up through the long ordeal.

Her reaction to the diagnosis was “a mixture of shock, horror and relief, which I think all of us felt as well,” Senanayake said.

The worm’s journey ended in the Australian National Wildlife Collection, where its head and tail are preserved, according to the study.