Blood

Repurposed blood cancer drug could remove need for lifelong HIV meds

A new study has repurposed an existing blood cancer drug, using it to eliminate dormant HIV-infected cells that can cause the infection to reactivate when suppressive antiretroviral treatment is interrupted. The drug could change the lives of people with HIV, doing away with the lifelong need to take medication as well as paving the way to a cure for the disease.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is highly effective at suppressing the replication of the HIV-1 virus in the body, reducing HIV in the blood to an undetectable level. However, when ART is stopped, it can cause latent infection, permanently hibernating in resting CD4+ T cells, to rebound or reactivate. This means that people living with HIV must take ART for the rest of their lives or risk a flare-up of the infection.

Finding ways to target and eradicate the latent HIV reservoir has presented a major challenge to researchers. Now, a preclinical study led by Australian researchers at WEHI and The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity has found that, when used alone, venetoclax, a drug currently used to treat blood cancers, can delay the reactivation of the dormant virus by two weeks, even in the absence of ART.

“In attacking dormant HIV cells and delaying viral rebound, venetoclax has shown promise beyond that of currently approved treatments,” said Philip Arandjelovic, the study’s lead author. “Every achievement in delaying this virus from returning brings us closer to preventing the disease from re-emerging in people living with HIV, Our findings are hopefully a step towards this goal.”

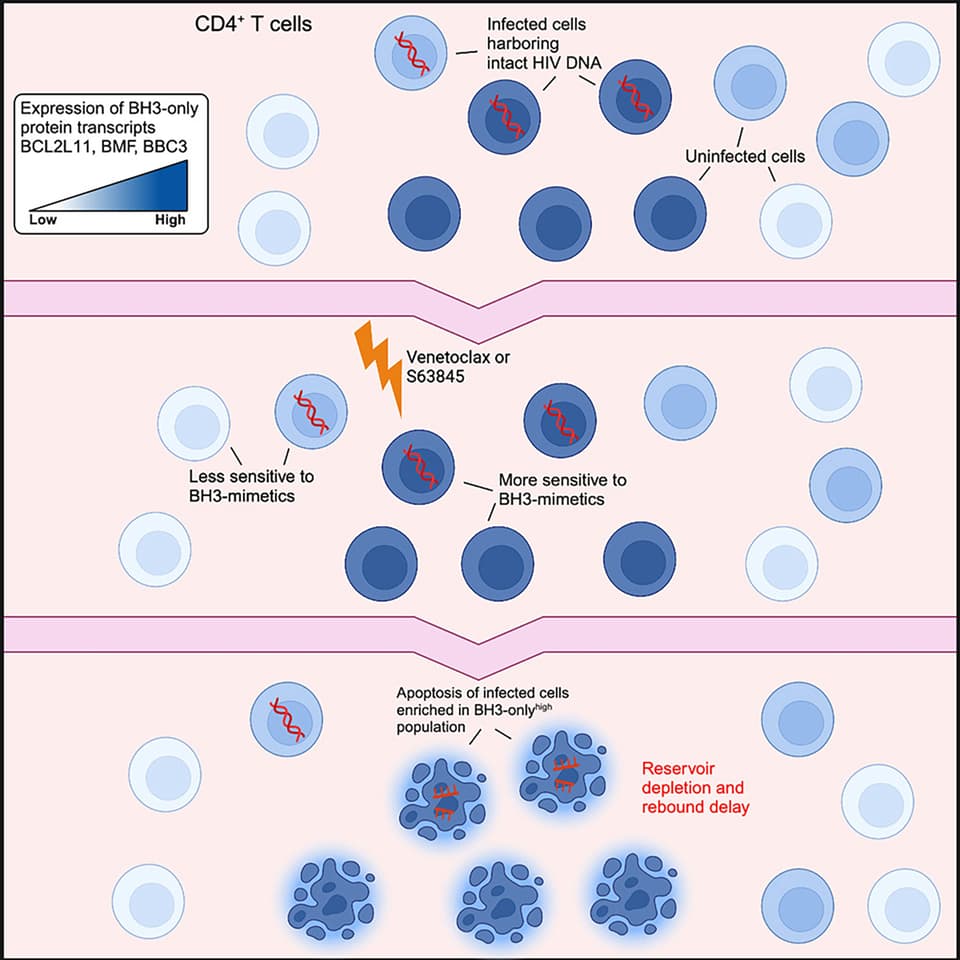

Blood cancers such as leukemia or lymphoma produce high levels of apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), a ‘pro-survival’ protein that stops cancer cells from destroying themselves. Venetoclax, marketed as Venclexta, is a targeted therapy known as a BH3 mimetic that specifically blocks Bcl-2, leading to the programmed death of cancer cells.

Other studies have explored whether venetoclax could kill latent infected cells, but the current study is the first time the drug has been used alone to test its effectiveness against persistent HIV infection.

The researchers administered ART to mice infected with HIV-1, which suppressed the infection. To investigate the importance of Bcl-2 in HIV-1 persistence in the presence of ART, the mice were given venetoclax every weekday for three weeks, a dose that corresponds to what the average human adult would be given. At the end of treatment, ART was interrupted, and the researchers assessed the viral load of the mice.

Following the three-week regimen, both control- and venetoclax-treated mice rebounded within two weeks of ART being interrupted. Overall, there was no difference in the time to rebound between treatment and control groups.

The researchers then tested the effect of giving HIV-infected mice treated with ART venetoclax for six weeks. In the control group mice, the virus rebounded within one week of ART interruption, but in 62.5% of mice that received venetoclax for six weeks, the virus did not rebound until two weeks after ART was interrupted. In 25% of mice, the virus did not rebound until three weeks post-ART.

Because their findings suggested that not all infected cells were sensitive to Bcl-2 inhibition over a six-week course of treatment, the researchers combined venetoclax with another BH3 mimetic, the Mcl-1 inhibitor S63845. Mcl-1 is another pro-survival protein and a critical regulator of T cell development and survival.

They found that treatment with S63845 alone for three weeks did not significantly delay viral rebound. However, using combined treatment with venetoclax and S63845 for three weeks, the researchers found that in 50% of mice, viral rebound occurred two weeks post-ART discontinuation, and in the other 50%, the rebound time was four weeks. S63845 is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials for blood cancers and is not yet on the market.

Arandjelovic et al./WEHI

“It has long been understood that one drug may not be enough to completely eliminate HIV,” Arandjelovic said. “This finding has supported that theory, while uncovering venetoclax’s powerful potential as a weapon against HIV.”

Using CD4+ T cells donated by people living with HIV and taking ART, the researchers also found that venetoclax significantly reduced the amount of HIV DNA found in these white blood cells.

“This indicates that venetoclax is selectively killing the infected cells, which rely on key proteins to survive,” said Youry Kim, co-lead author of the study. “Venetoclax has the ability to antagonize one of the key survival proteins.”

Release of the study’s findings has generated comment from others in the medical community.

“These results suggest that this combination of drugs could be explored in helping to find a pathway to an HIV cure or prolonged remission,” said Anthony Kelleher, Director of the Kirby Institute and a clinical immunologist at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney. “Although humanized mice are a standard model in which to study HIV therapeutics, results may not be transferrable to humans living with HIV, either in terms of efficacy or in terms of their side effect profile or toxicities, which can only be determined by systematic assessment through well-designed human clinical trials.”

A phase I/IIb clinical trial using venetoclax to treat HIV is due to commence in Denmark at the end of this year, with plans to extend the study to Melbourne in 2024.

“The trial will assess the safety and tolerability of venetoclax in people living with HIV who are on suppressive antiretroviral therapy,” said Marc Pellegrini, a joint corresponding author of the study.

The researchers remain optimistic about the therapeutic potential of the treatment.

“It’s exciting to see venetoclax, which has already helped thousands of blood cancer patients, now being repurposed as a treatment that could also help change the lives of people living with HIV and put an end to the requirement for lifelong medication,” said study co-author Sharon Lewin.

The study was published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

Source: WEHI