Cardiovascular

Incorporation of Shared Decision-Making in International Cardiovascular Guidelines

Key Points

Question

Is shared decision-making (SDM) integrated into cardiovascular guideline recommendations on pharmacotherapy?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 65 guidelines (2655 pharmacotherapy recommendations) published from 2012 to 2022 found that 6% of recommendations incorporated SDM in some form. The proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporating SDM was comparable across societies, with no trend for change over time, and only 3% of SDM recommendations were impartial and supported by a decision aid.

Meaning

These findings suggest that SDM was infrequently promoted and facilitated across cardiovascular guidelines.

Importance

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a key component of the provision of ethical care, but prior reviews have indicated that clinical practice guidelines seldom promote or facilitate SDM. It is currently unknown whether these findings extend to contemporary cardiovascular guidelines.

Objective

To identify and characterize integration of SDM in contemporary cardiovascular guideline recommendations using a systematic classification system.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study assessed the latest guidelines or subsequent updates that included pharmacotherapy recommendations and were published between January 2012 and December 2022 by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Data were analyzed from February 21 to July 21, 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

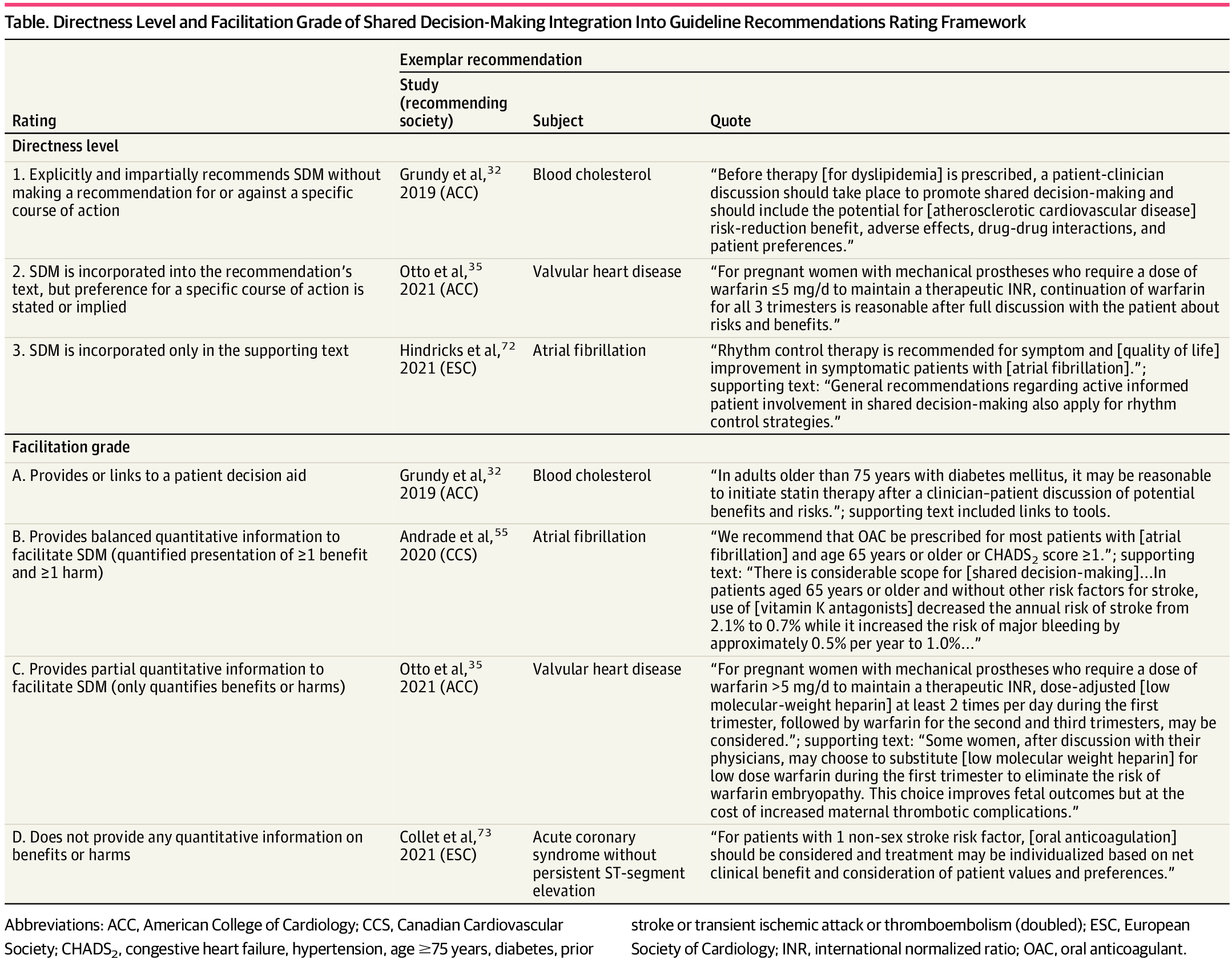

All pharmacotherapy recommendations were identified within each guideline. Recommendations that incorporated SDM were rated according to a systematic rating framework to evaluate the quality of SDM incorporation based on directness (range, 1-3; assessing whether SDM was incorporated directly and impartially into the recommendation’s text, with 1 indicating direct and impartial incorporation of SDM into the recommendation’s text) and facilitation (range, A-D; assessing whether decision aids or quantified benefits and harms were provided, with A indicating that a decision aid quantifying benefits and harms was provided). The proportion of recommendations incorporating SDM was also analyzed according to guideline society and category (eg, general cardiology, heart failure).

Results

Analyses included 65 guideline documents, and 33 documents (51%) incorporated SDM either in a general statement or within specific recommendations. Of 7499 recommendations, 2655 (35%) recommendations addressed pharmacotherapy, and of these, 170 (6%) incorporated SDM. By category, general cardiology guidelines contained the highest proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporating SDM (86 of 865 recommendations [10%]), whereas heart failure and myocardial disease contained the least (9 of 315 recommendations [3%]). The proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporating SDM was comparable across societies (ACC: 75 of 978 recommendations [8%]; CCS: 29 of 333 recommendations [9%]; ESC: 67 of 1344 recommendations [5%]), with no trend for change over time. Only 5 of 170 SDM recommendations (3%) were classified as grade 1A (impartial recommendations for SDM supported by a decision aid), whereas 114 of 170 recommendations (67%) were grade 3D (SDM mentioned only in supporting text and without any tools or information to facilitate SDM).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study across guidelines published by 3 major cardiovascular societies over the last decade, 51% of guidelines mentioned the importance of SDM, yet only 6% of recommendations incorporated SDM in any form, and fewer adequately facilitated SDM.

Introduction

Shared decision-making (SDM) is an essential aspect of the provision of ethical care, as it facilitates patient self-determination.1-3 Despite this, the current standard of care does not adequately inform nor involve patients in decision-making.4-9 For instance, a 2022 qualitative study of anticoagulant prescribing for atrial fibrillation10 found that clinicians provided unbalanced information regarding pros and cons, used persuasive language, were often unable to provide concrete cost information, and used direct-to-consumer advertising as an educational tool.

Clinical practice guidelines are well-positioned to promote and facilitate SDM, given their ubiquitous use to inform clinicians and policy makers. Guideline writers could help facilitate such promotion by including recommendations that advocate for SDM when multiple viable health care options are available.11 Furthermore, guideline writers could facilitate SDM by providing balanced, quantitative information about each treatment option, such as benefits, harms, and costs, or by encouraging use of evidence-based decision aids in their recommendations.3,12-15 Early studies aiming to quantify the extent of SDM incorporation in guidelines have identified substantial gaps, with less than 1% of the text dedicated to addressing the role of SDM in 5 major Canadian guidelines,16 and few prevention guidelines including any statements regarding patients’ values and preferences or providing quantitative estimates of benefits and harms.17,18

These studies suggest gaps and variability in the promotion and facilitation of SDM among guidelines; however, it is unknown whether these findings extend to a broad set of contemporary cardiovascular practice guidelines. The objectives of this study were to identify and characterize the integration of SDM, using a systematic classification system, among all pharmacotherapy recommendations within contemporary cardiovascular guidelines.

This cross-sectional study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Given that we used only published data without any patient-specific information, an ethics review board was deemed unnecessary for the study.

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

One author (B.J.M.) searched the guideline libraries of 3 cardiovascular societies for all guidelines published between January 1, 2012 and January 25, 2023: American College of Cardiology (ACC), Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Documents not formally classified as guidelines (eg, clinical practice updates, position statements, expert consensus documents, appropriate-use criteria, and performance measures) were excluded, as these documents generally do not undergo a formal voting process or include clinical recommendations.

We reviewed the latest version of all comprehensive guidelines and any subsequent focused updates, and we included 65 documents19-83 with at least 1 pharmacotherapy recommendation. We focused on recommendations pertaining to pharmacotherapy, since such recommendations are predominantly amenable to SDM and were within the scope of content expertise of the authors.

General Statements Promoting SDM

We performed a post hoc evaluation of overarching statements in support of SDM to further characterize the incorporation of SDM statements within guidelines as a whole. For a guideline to meet this criterion, it needed to contain at least 1 general statement (ie, statements broadly applicable across interventions and patient populations) expressing the significance of SDM or encouraging its implementation.

Identifying Recommendations Integrating SDM

We reviewed all pharmacotherapy recommendations to identify those that integrated SDM, either directly or via supporting text, by searching each guideline document for the following keywords: decision aid, discuss, informed decision, joining in, partake or partaking, partner, patient-centered, patient choice, patient contribution, patient education, patient goal, patient involvement, patient priorities, preference, values, shared decision, and sharing. We also searched specifically for www. to identify links to online decision aids. Recommendations were classified as incorporating SDM if they acknowledged any role for patient values or preferences in the decision. One author (B.J.M.) screened all pharmacotherapy recommendations for SDM incorporation. The other author (R.D.T.) then independently audited a random sample of 300 (approximately 10%) pharmacotherapy recommendations, masked to the first author’s inclusions, along with all pharmacotherapy recommendations classified as incorporating SDM by the first reviewer. Disagreements were resolved via discussion until consensus was reached.

Characterizing SDM Integration

To appraise the quality of SDM integration, we developed a systematic rating framework, which rates each recommendation in 2 dimensions: directness, which represents the extent to which SDM is explicitly recommended with impartiality to viable options; and facilitation, which represents the extent to which the recommendation enables the implementation of SDM. Directness was rated on a scale of 1 to 3 levels, with lower level indicating more direct recommendation. Facilitation was graded on a scale of A to D, with A indicating the best and D, the worst. The final rating framework is provided in the Table, and the first iteration of this system is available in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Both authors developed the framework iteratively while initially reviewing recommendations and then rated each pharmacotherapy recommendation using the final rating framework. Disagreements were resolved via discussion until consensus was reached.

Data Extraction

For each included guideline, 1 author (B.J.M.) extracted the following data: lead author last name, year published, society, whether it was an update or standalone guideline, the condition of focus, page count, word count (introduction to conclusion), number of authors, number of authors with no reported conflict of interest, total number of recommendations, whether the guideline contained at least 1 general statement promoting SDM, and all pharmacotherapy recommendations and relevant supporting text. Guidelines were further categorized into the following groups, adapted from a prior study84: general cardiology; congenital, valvular, and aortic diseases; coronary artery disease; electrophysiology; and heart failure and myocardial disease.

Statistical Analysis

We report the frequency and percentage of pharmacotherapy recommendations that incorporated SDM, along with the number of guidelines that included at least 1 pharmacotherapy recommendation incorporating SDM. We explored time-trends by comparing the proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations that incorporated SDM by year (2012-2022), along with the total number of pharmacotherapy recommendations in the same year. Additionally, we assessed patterns based on condition category and guideline society (ACC, CCS, and ESC). We used Microsoft Excel (Version 2306) to perform all analyses. Data were analyzed from February 21 to July 21, 2023.

Between January 2012 and December 2022, the ACC, CCS, and ESC published a total of 74 guidelines, and we included 65 guidelines that incorporated at least 1 pharmacotherapy recommendation. There were a total of 7499 recommendations with 2655 pertaining to pharmacotherapy (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The reviewed guidelines totaled 4758 pages (2 182 969 words) with 1487 authors, of whom 409 declared no conflict of interest (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

General Statements Supporting SDM

Of the 65 included guidelines,19-83 33 guidelines19-24,26-39,43,44,48,55,61,70,72,75,77,78,80,82,83 (51%) included at least 1 statement expressing the importance of SDM or promoting its implementation. These 33 guidelines encompassed 1512 of 2655 pharmacotherapy recommendations (57%). The proportion of guidelines containing these general statements differed by guideline society (ACC: 20 of 21 guidelines [95%]; CCS: 9 of 28 guidelines [25%]; ESC: 4 of 16 guidelines [32%]).

Recommendations That Integrated SDM

A total of 170 recommendations (6%) from 29 guidelines19-25,32-36,39,41,43-45,50,55,59,61,64,68,72,73,78,81,82 incorporated SDM at some level. There was no apparent trend in this proportion over time (Figure 1). General cardiology guidelines contained the highest proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporating SDM (86 of 865 recommendations [10%]), whereas heart failure and myocardial disease (9 of 315 recommendations [3%]) contained the least (Figure 2). The 3 societies had a similar proportion of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporating SDM (ACC: 75 of 978 recommendations [8%], CCS: 29 of 333 recommendations [9%], ESC: 67 of 1344 recommendations [5%]) (Figure 3). There was complete agreement between reviewers regarding whether the audited subset of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporated SDM.

Characterizing SDM Integration in Recommendations

Figure 4 provides the directness level and facilitation grade of SDM incorporation. Of 170 pharmacotherapy recommendations integrating SDM, only 5 recommendations (3%) received the highest rating of 1A (impartial recommendations for SDM supported by a decision aid), while 114 recommendations (67%) received the lowest rating of 3D (SDM mentioned only in supporting text and without any tools or information to facilitate SDM). The ACC 2018 cholesterol guideline32 consistently and meaningfully incorporated SDM throughout their recommendations, with a large number of recommendations referring to a decision aid (grade A based on our framework). Across guideline societies, most recommendations were level 3 or grade D (Figure 3).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 65 cardiovascular guidelines published by 3 international cardiovascular societies, 51% broadly supported the importance of SDM, yet only 6% of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporated SDM in some form. Among 170 recommendations that incorporated SDM, most merely noted the importance of patient preferences in the supporting text without addressing how to integrate these preferences into decision-making. These findings were consistent over the 10-year period and were similar across cardiovascular categories and between societies.

Despite these overall results, 2 identified guidelines exemplified commendable SDM incorporation. Specifically, 43% of the pharmacotherapy recommendations in the ACC 2018 cholesterol guideline incorporated SDM (approximately 7 times higher than the mean), with 32% of these recommendations receiving a grade A (indicating that a decision aid was provided).32 These recommendations are further supported by a general statement emphasizing the importance of SDM implementation. Additionally, the CCS 2022 cardiometabolic guideline reported a summary of findings table that could be used to facilitate SDM by providing estimates of benefit on patient-oriented efficacy outcomes.44

These exceptions aside, our overall findings echo and expand on the results of a 2007 review16 of major Canadian guidelines on diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and osteoporosis, in which only 0.1% of the total words in the guidelines related to SDM and patient preferences. Facilitation of SDM was likewise found to be poor, as necessary information was either missing or presented in an imbalanced manner. Similarly, a 2019 review17 found that only 39% of osteoporosis guidelines included any statements regarding patients’ beliefs, values, and preferences. A 2020 review18 of 13 coronary artery disease and diabetes guidelines found estimates of absolute benefit or harm in only 25% of recommendations, and only 3% included both a benefit and a harm. This indicates that these issues are widespread and have not noticeably improved over time.

The inclusion of broad statements supporting the principles and role of SDM in patient care is an important starting point, and the ACC’s guidelines are leaders in cardiovascular guidelines in this respect. Such broad statements serve as acknowledgments of the central role of patient values in decision-making but may not provide the support necessary for busy clinicians who are already faced with serious time constraints in implementing guideline-directed care.85 Several approaches could be undertaken to improve the incorporation of SDM into future guidelines. The Guidelines International Network has published a public toolkit for guideline development,15 in which 1 chapter is devoted to describing several possible SDM integration strategies. Some examples of these strategies include changing the wording of recommendations to promote discussion, presenting the absolute benefits and harms of interventions, and incorporating decision aids. The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence also recently published a guideline exclusively on how to integrate SDM into patient care across conditions and settings, as well as at an organizational level.86 Alternatively as a starting point, guideline panels could adopt a simplified approach. First, they could identify recommendations amenable to SDM, particularly weak and conditional recommendations that by their nature have at least 2 reasonable options. However, this should not preclude use of SDM in situations where strong recommendations are made. Second, recommendations that integrate SDM should be worded impartially with explicit incorporation of patient values and preferences, ideally referencing any existing evidence on patient preferences. Finally, guideline panels should provide information syntheses on the benefits, harms, and other considerations, such as cost, to help inform patient decisions, ideally in the form of a decision aid (pre-existing or created as part of guideline development). In absence of a bespoke decision aid, a Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation summary of findings table outlining benefits and harms in absolute terms accompanying the recommendation can be used to facilitate SDM.87

Future research should also aim to better understand the reasons that guideline panels do not frequently incorporate SDM promotion or facilitation into individual recommendations. Such research should examine not only the barriers to incorporating SDM in this manner, but also the facilitators that enable certain guidelines to perform well on these metrics. Future research may also validate and incorporate this rating framework and use it to classify SDM incorporation in recommendations or monitor for changes over time. This longitudinal monitoring could assess the impact of the recently published SDM incorporation recommendations by the Guidelines International Network and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,86 which will require further time for integration into guideline development.15 This framework may also serve as an effective complement to the AGREE II checklist,88 which is used to appraise guideline development processes and reporting, without direct examination of SDM incorporation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, some of the included recommendations may not have been amenable to SDM (eg, recommendations pertaining to emergency situations or therapies with harm and no benefit); however, most of the included recommendations addressed chronic conditions with multiple viable treatment options. For example, among general cardiology guidelines, only 10% of pharmacotherapy recommendations incorporated SDM. Second, this method did not account for SDM integration found within incidental supporting text or supplemental documents unattached to the recommendations. Third, we did not perform a quality assessment of recommended decision aids and therefore did not differentiate between recommendations recommending high-quality from low-quality or unproven decision aids. Fourth, psychometric testing of the rating framework is ongoing, and interrater reliability among a broader set of raters is uncertain, though all SDM recommendations are provided in eTable 2 in Supplement 1 for readers to judge for themselves.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study found that across guidelines published by three major cardiovascular societies over the last decade, 51% of guidelines mentioned SDM, yet only 6% of recommendations incorporated SDM in any form, and even fewer adequately facilitated SDM. Future cardiovascular guidelines should further incorporate SDM into their recommendations to empower clinicians to engage patients in decision-making.

Accepted for Publication: August 8, 2023.

Published: September 7, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.32793

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2023 MacDonald BJ et al. JAMA Network Open.

Concept and design: Both authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Both authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: MacDonald.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Statistical analysis: MacDonald.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Turgeon.

Supervision: Turgeon.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Turgeon reported receiving a grant from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2.

References

KW, Mangione

CM, Barry

MJ,

et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Collaboration and shared decision-making between patients and clinicians in preventive health care decisions and US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. JAMA. 2022;327(12):1171-1176. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3267 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

C, Paget

L, Halvorson

G, Novelli

B, Guest

J, McCabe

P. Communicating with patients on health care evidence. NAM Perspectives. Published online September 25, 2012. doi:10.31478/201209d Google ScholarCrossref

K, Dolovich

L, Cassels

A,

et al. What patients want to know about their medications: focus group study of patient and clinician perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:104-110.PubMedGoogle Scholar

G, Scholl

I, Tietbohl

C,

et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):S14. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S14 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

N, Desroches

S, Robitaille

H,

et al. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):542-561. doi:10.1111/hex.12054 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

EP, Hollander

JE, Schaffer

JT,

et al. Shared decision making in patients with low risk chest pain: prospective randomized pragmatic trial. BMJ. 2016;355:i6165. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6165 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

R, Mancher

M, Miller Wolman

D, Greenfield

S, Steinberg

E, eds; Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/

J, Lindblad

AJ, Korownyk

C. Clinical practice guidelines have big problems: the fix is simple. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5(6):562-565. doi:10.1002/jac5.1623Google ScholarCrossref

T, Pieterse

AH, Koelewijn-van Loon

MS,

et al. How can clinical practice guidelines be adapted to facilitate shared decision making: a qualitative key-informant study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):855-863. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001502 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JP, Loewen

P. Adding “value” to clinical practice guidelines. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(8):1326-1327.PubMedGoogle Scholar

JEM, Marwah

A, Naeem

F, Yu

W, Meadows

L. Evidence of patient beliefs, values, and preferences is not provided in osteoporosis clinical practice guidelines. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(7):1325-1337. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-04913-y PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

M, Heinmüller

S, Hueber

S, Schedlbauer

A, Kühlein

T. Do guidelines help us to deviate from their recommendations when appropriate for the individual patient: a systematic survey of clinical practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(3):709-717. doi:10.1111/jep.13187 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SD, Gardin

JM, Abrams

J,

et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126(25):3097-3137. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182776f83PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

PT, Kushner

FG, Ascheim

DD,

et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78-e140. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

LA, Fleischmann

KE, Auerbach

AD,

et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(22):e77-e137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

EA, Wenger

NK, Brindis

RG,

et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CT, Wann

LS, Alpert

JS,

et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

RL, Joglar

JA, Caldwell

MA,

et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):e27-e115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.856PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

GN, Bates

ER, Bittl

JA,

et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1082-1115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

MD, Gornik

HL, Barrett

C,

et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):e71-e126. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.007PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

PK, Carey

RM, Aronow

WS,

et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127-e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

WK, Sheldon

RS, Benditt

DG,

et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(5):e39-e110. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SM, Stevenson

WG, Ackerman

MJ,

et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(14):e91-e220. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

FM, Schoenfeld

MH, Barrett

C,

et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(7):e51-e156. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.044PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

KK, Daniels

CJ, Aboulhosn

JA,

et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):e81-e192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1029PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SM, Stone

NJ, Bailey

AL,

et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):e285-e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

DK, Blumenthal

RS, Albert

MA,

et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):e177-e232. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CT, Wann

LS, Calkins

H,

et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104-132. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.011PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

CM, Nishimura

RA, Bonow

RO,

et al; Writing Committee Members. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25-e197. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SR, Mital

S, Burke

MA,

et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):e159-e240. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.045PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JS, Tamis-Holland

JE, Bangalore

S,

et al; Writing Committee Members. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

EM, Preventza

O, Hamilton Black Iii

J,

et al; Writing Committee Members. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(24):e223-e393. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.004PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

PA, Bozkurt

B, Aguilar

D,

et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(17):e263-e421. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JA, O’Meara

E, McDonald

MA,

et al. 2017 Comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(11):1342-1433. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.08.022PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SR, Bainey

KR, Cantor

WJ,

et al; members of the Secondary Panel. 2018 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology focused update of the guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(3):214-233. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.012PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

GC, Welsford

M, Ainsworth

C,

et al; members of the Secondary Panel. 2019 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology guidelines on the acute management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: focused update on regionalization and reperfusion. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35(2):107-132. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2018.11.031PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

GJ, Thanassoulis

G, Anderson

TJ,

et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(8):1129-1150. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2021.03.016PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

GBJ, O’Meara

E, Zieroth

S,

et al. 2022 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guideline for use of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for cardiorenal risk reduction in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38(8):1153-1167. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2022.04.029PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SA, Dent

S, Brezden-Masley

C,

et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for evaluation and management of cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(7):831-841. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.078PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

GBJ, Gosselin

G, Chow

B,

et al; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of stable ischemic heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(8):837-849. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2014.05.013PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

E, Parlow

J, MacDonald

P,

et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines on perioperative cardiac risk assessment and management for patients who undergo noncardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(1):17-32. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.09.008PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

R, Philippon

F, Shanks

M,

et al; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines on the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy: implementation. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(11):1346-1360. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.009PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

M, Virani

S, Chan

M,

et al. CCS/CHFS heart failure guidelines update: defining a new pharmacologic standard of care for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(4):531-546. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2021.01.017PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

E, McDonald

M, Chan

M,

et al. CCS/CHFS heart failure guidelines: clinical trial update on functional mitral regurgitation, SGLT2 inhibitors, ARNI in HFPEF, and tafamidis in amyloidosis. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(2):159-169. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2019.11.036PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JF, Bell

AD, Ackman

ML,

et al; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(11):1334-1345. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.07.001PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

M, Arthur

HM, Cook

A,

et al; Canadian Cardiovascular Society; Canadian Pain Society. Management of patients with refractory angina: Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Pain Society joint guidelines. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(2)(suppl):S20-S41. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2011.07.007PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

PF, Lougheed

J, Dancea

A,

et al; Children’s Heart Failure Study Group. Presentation, diagnosis, and medical management of heart failure in children: Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(12):1535-1552. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.08.008PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JG, Aguilar

M, Atzema

C,

et al; Members of the Secondary Panel. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society comprehensive guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(12):1847-1948. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2020.09.001PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

PM, Anastasakis

A, Borger

MA,

et al; Authors/Task Force members. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

R, Aboyans

V, Boileau

C,

et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines; The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(41):2873-2926. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu281PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

Y, Charron

P, Imazio

M,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921-2964. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

G, Lancellotti

P, Antunes

MJ,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075-3128. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

M, Bueno

H, Byrne

RA,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); ESC National Cardiac Societies. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Coronary Artery Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(3):213-260. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

B, James

S, Agewall

S,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

V, Ricco

JB, Bartelink

MEL,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries endorsed by the European Stroke Organization (ESO) the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(9):763-816. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

V, Roos-Hesselink

JW, Bauersachs

J,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165-3241. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

SV, Meyer

G, Becattini

C,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543-603. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

J, Katritsis

DG, Arbelo

E,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia: the Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(5):655-720. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

F, Grant

PJ, Aboyans

V,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):255-323. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

F, Baigent

C, Catapano

AL,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111-188. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

G, Potpara

T, Dagres

N,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373-498. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

JP, Thiele

H, Barbato

E,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(14):1289-1367. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

A, Sharma

S, Gati

S,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(1):17-96. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa605PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

FLJ, Mach

F, Smulders

YM,

et al; ESC National Cardiac Societies; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(34):3227-3337. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

K, Tfelt-Hansen

J, de Riva

M,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(40):3997-4126. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

AR, López-Fernández

T, Couch

LS,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. 2022;43(41):4229-4361. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

S, Mehilli

J, Cassese

S,

et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3826-3924. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac270PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

AC, Califf

RM, Windecker

S, Smith

SC

Jr, Lopes

RD. Levels of evidence supporting American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology Guidelines, 2008-2018. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1069-1080. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1122 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

HJ, Higgins

JP, Vist

GE,

et al. Completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In: Higgins

JPT, Thomas

J, Chandler

J,

et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley; 2019:375-402. doi:10.1002/9781119536604.ch14

MC, Kho

ME, Browman

GP,

et al; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090449 PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref