Cardiovascular

Ferid Murad, who won Nobel Prize for cardiovascular discovery, dies at 86

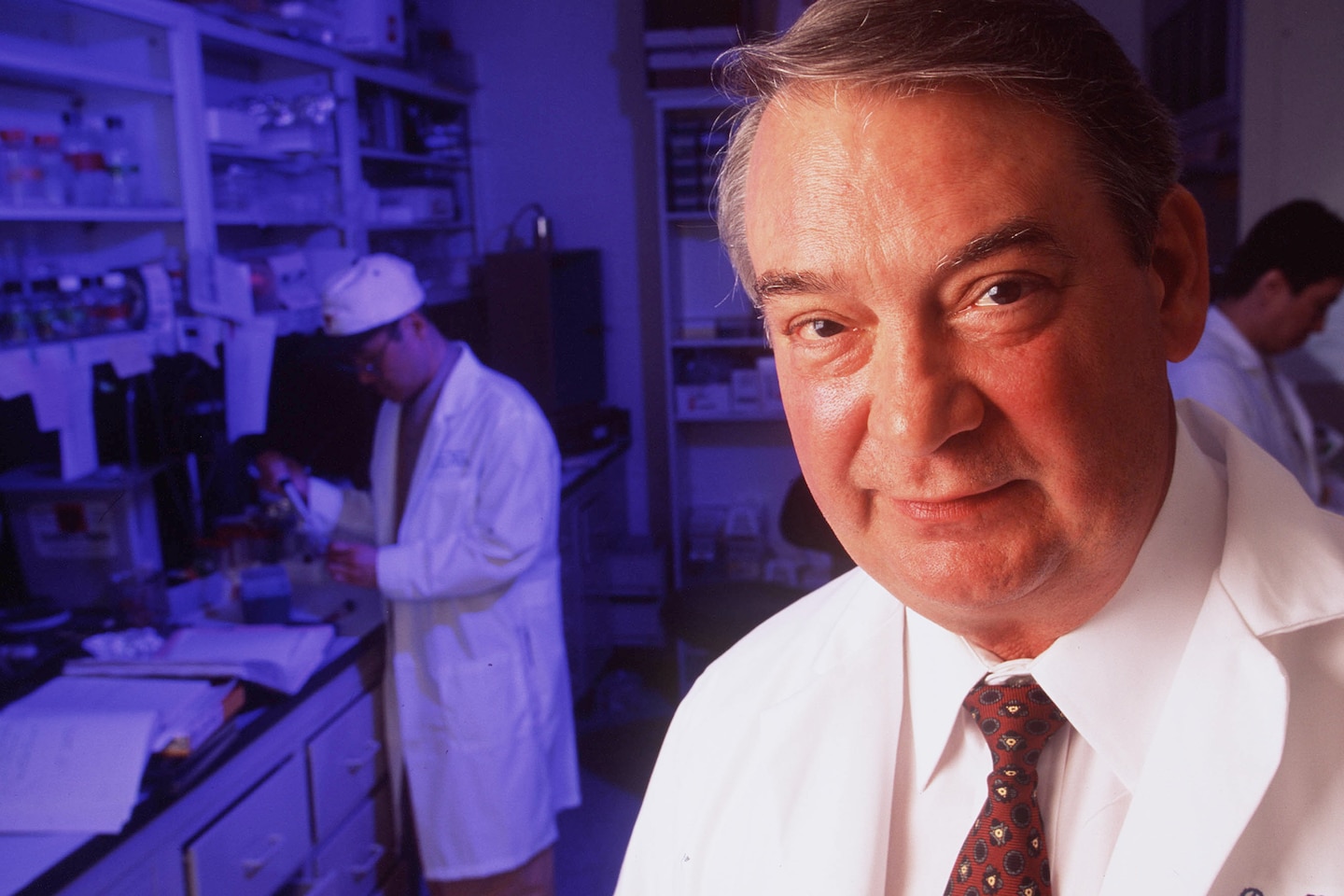

Ferid Murad, a pharmacologist who shared a Nobel Prize in 1998 for discovering that nitric oxide, an air pollutant, plays a key role in relaxing blood vessels, a startling finding that led to treatment advances in heart disease, erectile dysfunction and breathing struggles in premature infants, died Sept. 4 at his home in Menlo Park, Calif. He was 86.

His son, Joe Murad, confirmed his death but did not give a cause.

Dr. Murad’s discovery dates to the 1970s, when he began studying nitroglycerin, the substance that Alfred Nobel, the namesake of the annual awards given in medicine and other disciplines, used to invent dynamite in 1867.

Nobel’s factory workers were the first to notice a curious side effect of the explosive substance. Any chest pains they had from hard labor vanished when they inhaled nitroglycerin fumes inside the factory. Soon, doctors began trying it as a remedy for angina, hypertension and other cardiovascular maladies.

Nitroglycerin became a common treatment for heart ailments, but until Dr. Murad began studying it at the University of Virginia, nobody understood how or why it worked. Through a series of experiments, Dr. Murad discovered that nitroglycerin releases nitric oxide, which relaxes smooth muscle cells.

The scientific world didn’t immediately embrace the idea that a toxic substance could have such profound biological effects.

“Many of our colleagues,” Dr. Murad said, “thought we were crazy.”

Larry Keefer, then a chemist at the National Cancer Institute, was one of the skeptics.

“I’d been studying nitric oxide as a toxicological factor, and initially I thought this was not possible,” he told NPR after Dr. Murad won the award. “But, in fact, as example after example of important bioregulatory roles came out, the rest of us just had to believe it. It was a revolutionary claim, and it stood up.”

Dr. Murad’s discovery contributed to the development of Viagra, which helps produce erections by dilating blood vessels. Premature infants have been treated with low concentrations of nitric oxide to improve breathing, though some recent studies have questioned the efficacy and suggested narrowing its use. Nitric oxide is used to treat other lung and cardiovascular diseases. It is being studied for multiple other conditions.

Dr. Murad was working at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston when he won the 1998 Nobel in Physiology or Medicine, sharing the prize with two other pharmacologists who studied nitric oxide: Robert F. Furchgott of the State University of New York in Brooklyn, and Louis Ignarro of the University of California at Los Angeles.

In announcing the award, the Swedish organization noted its namesake had been prescribed nitroglycerin for heart disease.

“Isn’t it the irony of fate that I have been prescribed [nitroglycerin] to be taken internally!” he wrote in a letter. “They call it Trinitrin, so as not to scare the chemist and the public.”

Ferid Murad was born in Whiting, Ind., on Sept. 14, 1936. He was known most of his life as Fred. His father, an Albanian immigrant, and mother owned a restaurant. Along with his two brothers, Fred worked long hours in the restaurant washing dishes, taking orders and running the cash register.

“With this background,” he later wrote, “I knew that I wanted considerable education so I wouldn’t have to work as hard as my parents.”

In eighth grade, he wrote an essay identifying his top three career choices as physician, teacher and pharmacist. He later became a version of all three: a medical doctor with a PhD in pharmacology who did clinical research and taught at several universities.

Dr. Murad was a pre-med and chemistry major at DePauw University in Greencastle, Ind., where he graduated in 1958, the same year he married Carol Leopold, an English and Spanish major at the school. He received his medical degree and doctorate in pharmacology from Western Reserve University in Cleveland (later Case Western Reserve University) in 1965.

In addition to the University of Virginia and the University of Texas Health Science Center, Dr. Murad also conducted research at the National Institutes of Health, Stanford University and George Washington University. In the private sector, he worked at Abbott Laboratories and founded Molecular Geriatrics, a biotechnology company.

Along with his son, of Portola Valley, Calif., Dr. Murad is survived by his wife; four daughters, Christy Kuret of Dublin, Ohio, Carrie Rogers of Lake Bluff, Ill., Marianne Delmissier of Plainfield, Ill., and Julie Birnbaum of Alamo, Calif.; and nine grandchildren.

Dr. Murad learned that he won the Nobel when he was awakened by a 4 a.m. phone call from Sweden. Almost instantly, he became a scientific star. Visiting Washington, he met with President Bill Clinton and William Rehnquist, the chief justice of the United States. At a dinner hosted by the Swedish ambassador, Dr. Murad and his wife met best-selling author Frank McCourt.

“This is the greatest day of my life,” Carol Murad told her husband.

Dr. Murad and his co-winners split the $978,000 award that came with winning the Nobel Prize. He used some of that money to fly 51 family members, colleagues and friends to the ceremony in Stockholm, after which his wife revised her earlier declaration.

“This,” she said, “was the greatest day of my life.”