Cancer and neoplasms

Healthy 90-year-old woman presents with proptosis, diplopia

September 11, 2023

7 min read

Source/Disclosures

Published by:

Disclosures:

Caranfa and Shi report no relevant financial disclosures

A 90-year-old woman was referred by her ophthalmologist to the emergency department at our institution following several weeks of discomfort and a “pinching” sensation in the left eye.

Initial examination near the time of symptom onset was notable for limited left abduction, which was diagnosed as a left sixth cranial nerve palsy. The remainder of the documented exam was unremarkable, but given the patient’s age, she was ordered for a C-reactive protein test (which returned within normal limits) and an MRI of the brain and orbits. The MRI demonstrated an acute abnormality, prompting referral to the emergency room for further evaluation.

Source: Angell Shi, MD, and Alison Callahan, MD

On her arrival at Tufts, the patient revealed that 6 months before evaluation, she had begun having binocular diplopia with left gaze only while driving. One month prior, the patient and her daughter had noticed that the left eyelid appeared droopy. She denied any systemic symptoms, including any focal neurologic deficits. Her ocular history included pseudophakia and glaucoma suspect in both eyes. Her medical history included chronic left shoulder pain and osteoarthritis, thalassemia minor, and chronic lichen sclerosus for which she was concurrently being followed by her gynecologist. A vulvar biopsy, which had been recently performed, showed squamous cell carcinoma in situ. She took only vitamin D and a probiotic and was not on any other medications. She lived alone and functioned independently.

Examination

Visual acuity with correction measured 20/40-2 in both eyes (20/30- with pinhole). The patient had a 1 mm anisocoria, symmetric in both light and dark, with a long-standing smaller left pupil. IOPs were 14 mm Hg and 15 mm Hg. Visual fields were full to confrontation. Extraocular motility testing revealed left abduction, adduction and supraduction deficits. External examination demonstrated a mild left ptosis (margin reflex distance 1 of 5 mm on the right and 3 mm on the left) and 1 mm of lagophthalmos on the left. Exophthalmometry was notable for 3 mm of relative left proptosis. Slit lamp examination was notable only for mild punctate epithelial erosions of the left eye and pseudophakia in both eyes. Optic nerves were slightly large (cup-to-disc ratio of 0.6) but with no pallor or disc edema. She had mild small drusen in both maculae, but the remainder of the fundus exam was normal.

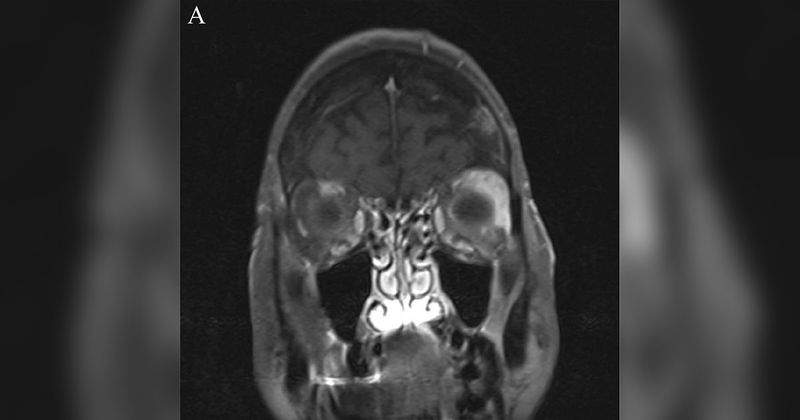

The patient’s MRI demonstrated moderate diffuse enlargement of the left lateral rectus muscle with mildly increased T2 signal intensity and hyperenhancement without restricted diffusion (Figures 1 and 2). The remainder of the MRI was unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

See answer below.

Orbital mass

This elderly patient with unilateral ptosis, proptosis, diplopia, motility limitations and abnormal orbital mass on MRI has a metastatic lesion to the orbit. In patients of this age group and presentation, neoplasm (either primary or metastatic) is by far the most likely diagnosis. Primary neoplasms may be either benign or malignant, and in the orbit, the most common primary tumor is of lymphoproliferative etiology. Metastatic lesions may arise from a variety of primary sites.

Inflammatory causes such as IgG4-related disease, idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and dacryoadenitis may have similar presentations in the orbit but typically present at younger ages. Infectious etiologies such as orbital cellulitis or abscess would not be likely in a well-appearing patient with no pain and symptoms ongoing for several months. Although vascular etiologies including carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous hemangioma, and venous or lymphatic malformation could present with proptosis, they appear distinct on radiographic imaging, have characteristic clinical features and usually manifest earlier in life.

Thyroid-associated orbitopathy is a common cause of proptosis, diplopia and restrictions in motility with enlargement of the extraocular muscle, as seen in this patient. However, classic tendon-sparing muscle enlargement would be anticipated (vs. diffuse as is this case), the lateral rectus is the single least likely muscle to be involved with thyroid eye disease, and eyelid retraction rather than ptosis would be an expected finding.

Workup and management

Assessment of orbital masses requires both clinical and radiographic evaluation, as they can rarely be differentiated by clinical examination alone. Broadly, inquiring about medical history and determining the presence or absence of pain, proptosis, periocular changes, progression and pulsation can help narrow down the differential. CT imaging or MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast, fat suppression and diffusion-weighted imaging is best for visualization. Diffusion-weighted imaging tends to be most helpful in distinguishing malignant from benign lesions, especially of lymphoproliferative origin. Certain radiographic characteristics may also help characterize types of lesions. Benign tumors are more often oval shaped, may deform neighboring structures, and can cause hyperostosis of surrounding bone. Malignant lesions are typically diffuse, irregularly shaped, and infiltrative or else “mold” to the globe or other surrounding structures as seen in lymphoproliferative neoplasms. Malignancies will more often cause bony erosion rather than growth.

Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for identification of orbital masses. Depending on the location of the mass, various approaches to orbitotomy can be taken. For example, an upper eyelid crease incision allows for access to lesions in superior and lateral orbit. Inferior orbital masses can be accessed through a transconjunctival lower orbitotomy with incisions through the inferior fornix and subtarsal conjunctiva. A lateral canthotomy with retrocanthal incision allows for access to the lateral orbit, while a transcaruncular approach provides access to medial lesions. Most commonly, incisional biopsy is performed, although excisional biopsy is considered when removal of the entire lesion is necessary for therapeutic purposes. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is another option, but its small cellular sample size limits pathologic analysis and is therefore not a preferred technique.

Additional workup such as laboratory testing can be helpful adjunctive tools to rule out diagnoses such as thyroid orbitopathy or IgG4-related disease.

Management of orbital metastasis is multidisciplinary and requires referral to oncology. Treatment is usually palliative with local radiation, which can reduce lesion size and improve orbital signs and symptoms. Surgery is generally avoided unless the tumor is very large and/or causing vision loss, in which case debulking can be performed. Chemotherapy can be used as an adjuvant for systemic disease.

Discussion

Orbital masses are uncommon in the general population, with an incidence of 2.02 per 1 million person-years. Primary lesions that arise from within the orbit account for the majority of orbital masses. In patients older than 60 years, orbital tumors are malignant in 63% of cases.

Orbital metastases are rare (approximately 4% to 8% of orbital masses) but can be devastating. They occur in 2% to 5% of patients with systemic malignancies. In a large patient series, Shields and colleagues reported that the most common primary site for orbital metastasis is the breast (53%), followed by the prostate gland (12%), lung (8%) and skin (6%). Metastasis to the orbit, if present at all, may not become apparent for months to years after diagnosis and identification of a primary cancer. However, in 15% to 25% of patients, it can be the first manifestation of cancer, as was the case in this patient. In these cases, it portends an especially poor prognosis. Although there is some variability depending on the type and source of primary cancer, the mean survival time after diagnosis of orbital metastasis is approximately 20 months. On average, the 1-year survival rate is approximately 40%.

Metastases frequently involve the extraocular muscles (due to their abundant vascular supply), orbital fat and/or bone. Patients are typically symptomatic, and most will experience rapidly progressive proptosis from infiltration and mass effect. However, metastases arising from scirrhous breast cancer may actually cause paradoxical enophthalmos from fibrosis causing contraction of orbital fat and resulting globe retraction. Other symptoms may include diplopia, restriction of extraocular motility, a palpable or visible mass, ptosis, eyelid swelling or a red eye. Orbital pain may be present. If there is compression of the optic nerve, patients may experience blurry or decreased vision, and a relative afferent pupillary defect can be seen.

Pathologic analysis of tissue is essential for diagnosis. Fresh, frozen and permanent sections can be sent from biopsy specimens for a range of studies. Flow cytometry, histochemistry and immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction and genetic sequencing, among other techniques, may be used for analysis. Depending on the provided history and gross histology, certain IHC stains may be selected by the pathologist to aid not only in diagnosis but for prognosis and therapeutic purposes as well. IHC stains allow for differentiation into cell lineages (for example, cytokeratin staining for epithelial cells), origin (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, or GCDFP-15, for mammary glands or other apocrine cells), and prognostic and therapeutic response (estrogen/progesterone receptors and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, or HER2, which determine candidacy for certain treatments).

Diagnosis of orbital metastasis requires a systemic evaluation with oncology to identify the primary site and any additional metastases, as well as to guide treatment. Treatment options may involve surgery, radiation and/or hormone therapy, based on hormone receptor status. For breast cancer, mammography is indicated. PET/CT imaging is useful for disease staging purposes and to establish the extent of the disease. Regardless of whether widespread metastatic disease is present, goals of care discussions should be held with patients and their families.

Clinical course continued

The patient underwent an orbital biopsy with a lateral extended upper eyelid crease approach. A dense white fibrous mass was noted intraoperatively. Fresh, frozen and permanent samples were submitted for tissue analysis. The final pathology diagnosis was invasive adenocarcinoma involving skeletal muscle fibers, with features consistent with invasive ductal adenocarcinoma with lobular differentiation of breast origin. Immunohistochemistry studies were positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors and negative for HER2/neu. Pancytokeratin, GATA3 (a nuclear marker expressed in epithelial neoplasms, including breast carcinoma) and GCDFP markers were positive. The patient was referred to an oncologist for further systemic workup and treatment. PET/CT imaging showed multiple lesions in the axial skeleton and lower outer quadrant of the right breast, suggestive of areas of metastases and primary malignancy, respectively. A diagnostic mammogram demonstrated suspicious calcifications in the right upper outer quadrant of the right breast, and she underwent a stereotactic-guided core needle biopsy of this area, which demonstrated grade 2 invasive lobular carcinoma. She is scheduled for further follow-up with medical and radiation oncology to determine the next steps for treatment.

- References:

- Demirci H, et al. Ophthalmology. 2002;doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00932-0.

- Ismailova DS, et al. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;doi:10.1007/s00417-018-4014-9.

- Miura A, et al. Clin Radiol. 2022;doi:10.1016/j.crad.2022.08.148.

- Mombaerts I, et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.06.006.

- Palmisciano P, et al. Cancers (Basel). 2021;doi:10.3390/cancers14010094.

- Shields JA, et al. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;doi:10.1097/00002341-200109000-00009.

- Tailor TD, et al. Radiographics. 2013;doi:10.1148/rg.336135502.

- Valenzuela AA, et al. Orbit. 2009;doi:10.1080/01676830902897470.

- Zaha DC. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.382.

- For more information:

- Edited by Jonathan T. Caranfa, MD, PharmD, and Angell Shi, MD, of New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].