Congenital disorders

SSRI Use During Pregnancy Alters the Child’s Brain Development

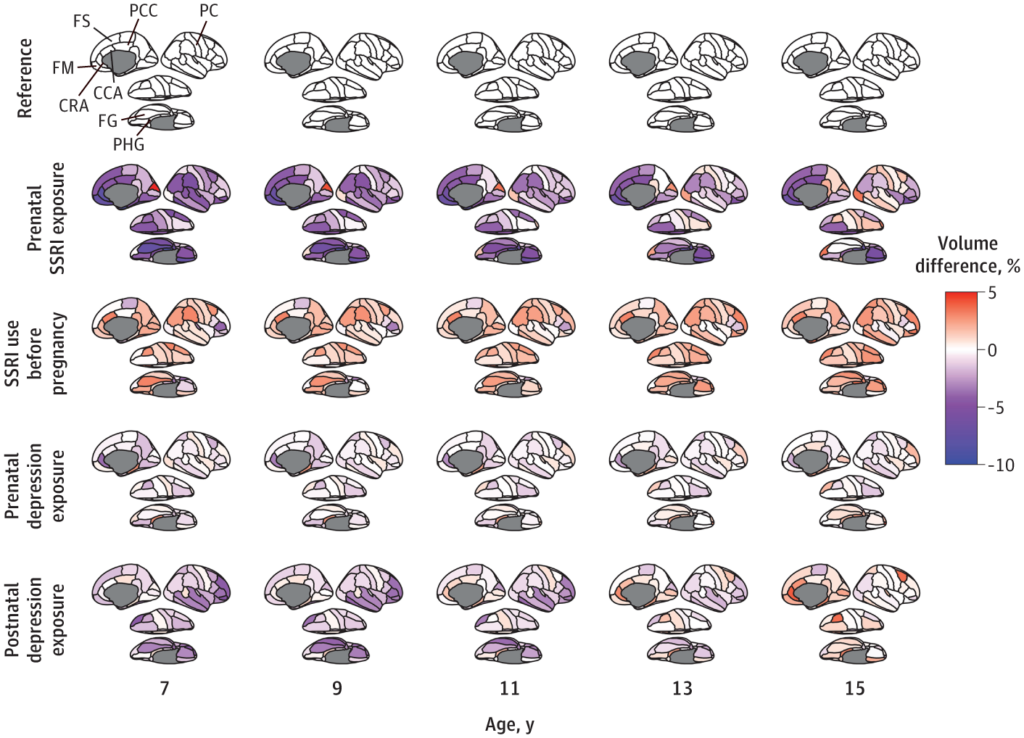

In a new study in JAMA Psychiatry, researchers found that children born to mothers who used SSRIs during pregnancy had reduced brain volume in multiple areas. Most brain volume reductions were still there at the follow-up when the kids were 15 years old. The researchers write that the affected areas of the brain are theorized to be involved in emotion regulation.

“The results of this cohort study suggest that prenatal SSRI exposure may be associated with altered developmental trajectories of brain regions involved in emotional regulation in offspring,” the researchers write.

The researchers were led by Dogukan Koc at Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. This was part of Generation R, a population-based study in Rotterdam. The study included 3,198 mothers with a delivery date between April 1, 2002, and January 31, 2006, and the children were followed with three brain scans over time, the last of which occurred when they were 15.

To account for factors such as the effect of underlying maternal depression and when, specifically, the mothers used antidepressants, the researchers split the cohort into five groups. There were 41 with SSRI use during pregnancy, 77 who only used SSRIs before pregnancy, 257 who did not use SSRIs but had depressive symptoms during pregnancy, 74 who had depressive symptoms only after giving birth, and 2,749 controls who had neither depressive symptoms nor SSRI use.

According to the researchers, there was a “persistent association between prenatal SSRI exposure and less cortical volumes across the 10-year follow-up period, including in the superior frontal cortex, medial orbitofrontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, rostral anterior cingulate cortex, and posterior cingulate.”

They add, “Prenatal SSRI exposure was consistently associated with lower volume, ranging from 5% to 10% in the frontal, cingulate, and temporal cortex across ages.”

So, could this be explained by the mother’s depression? No, write the researchers. For mothers who were depressed but did not take SSRIs, the children were almost no different from the healthy controls. Prenatal depression was associated with a smaller volume in one area, the rostral anterior cingulate gyrus. Similarly, postnatal depression was associated with a smaller volume in one area, the fusiform gyrus.

Those differences in one area each should be compared to the large, brain-wide reduction in volume in numerous areas experienced by kids whose mothers took SSRIs. Moreover, even in the fusiform gyrus, kids whose mothers took SSRIs had larger reductions in volume than kids whose mothers had depression but didn’t take SSRIs.

The good news is that some of these brain volume reductions appeared to have a catch-up effect: for instance, amygdala volumes had increased by age 15, so kids who were exposed to SSRIs were not any different from controls.

Unfortunately, many of the brain volume differences didn’t catch up. Moreover, it’s unclear what effect these volume differences throughout all of childhood would have on a kid’s development, even if it catches up by their late teenage years.

Previous Research

Studies have consistently found antidepressant use in pregnancy to be associated with myriad risks to neonatal health, including neonatal withdrawal syndrome, preterm birth, congenital disabilities, developmental problems, cardiopulmonary problems, and even death.

In one study, researchers found a sixfold increase in neonatal withdrawal syndrome when mothers took antidepressants. In another study, researchers found that 30% of babies born to mothers who used antidepressants experienced neonatal withdrawal syndrome. None of the babies whose mothers did not use antidepressants had this complication. And yet another study found that over half (56%) of babies exposed to SSRIs had this problem.

Researchers have argued that antidepressants should be discontinued in pregnancy because of this risk, which includes symptoms of hypoglycemia, tremors, hypotonia, hypertonia, tachycardia, rapid breathing, and respiratory distress in babies born to mothers who use antidepressants.

Studies have also accounted for preexisting factors like depression severity by comparing women who continued using antidepressants during pregnancy with women who had the same indication and did use antidepressants initially—but stopped after becoming pregnant. That study found that those who continued to use antidepressants increased the risk of neonatal health complications in their newborns, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and hospitalizations.

Other research has found that antidepressant use during pregnancy alters brain development in the fetus. These findings have appeared in top journals, too: A study in JAMA Psychiatry found that antidepressant use during pregnancy increased the risk of infants with speech disorders, while a study in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that antidepressant use during pregnancy increased the risk of impaired neurological functioning in infants.

****

Koc, D., Tiemeier, H., Stricker, B. H., Muetzel, R. L., Hillegers, M., & El Marroun, H. (2023). Prenatal antidepressant exposure and offspring brain morphologic trajectory. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online August 30, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.3161 (Link)