Cardiovascular

Work-focused healthcare from the perspective of employees living with cardiovascular disease: a patient experience journey mapping study

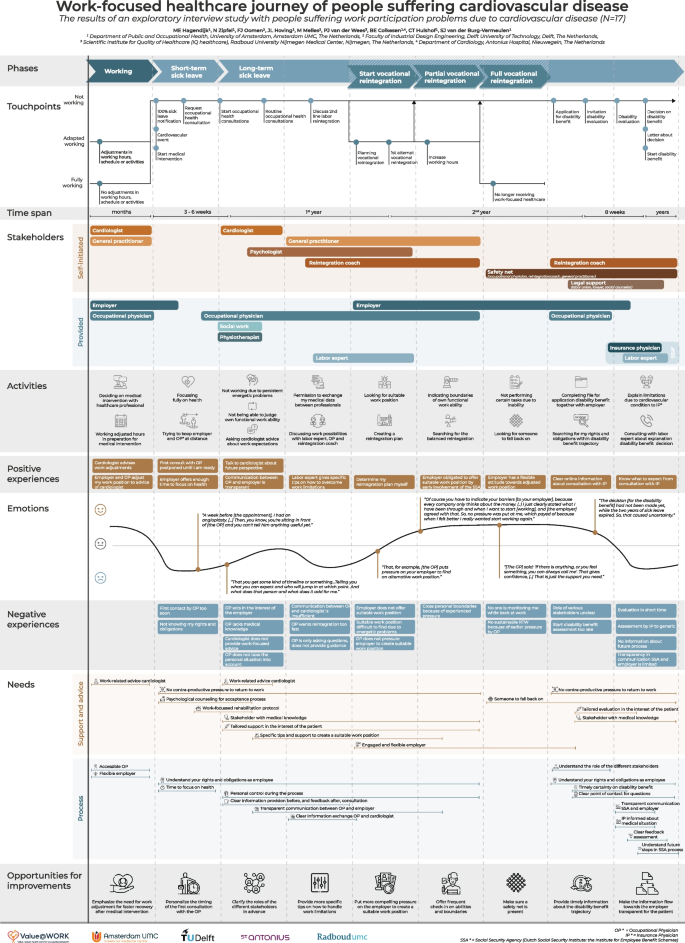

Figure 1 depicts the work-focused healthcare journey of people living with CVD that is aggregated based on all interview data. Based on the patients’ input six main phases are identified. The first phase, i.e. working, represents a period in which problems with health and functioning first occur. The next two phases, i.e. short-term sick leave and long-term sick leave, represent a period of full-time sick leave. The last three phases, i.e. start vocational reintegration, partial vocational reintegration, and full vocational reintegration, focus on the process of reintegration that takes place sometime within the two years after initial sick leave. This time frame is in concordance with the Dutch Gatekeeper Improvement Act, which provides guidelines for the employer and employee in order to get the sick-listed employee back to work as quickly as possible.

The work-focused healthcare journey of people living with cardiovascular disease. Figure 1 can also be opened in PdF via the

Additional file 2 for better zooming options. Legends: Vertical axis show the multiple building blocks this Patient experience journey map exists of. Horizontal axis shows the data of the multiple building blocks over time. IP = Insurance physician, OP = Occupational physician, RTW = return to work, SSA = Social security agency

The six phases are described below, providing further explanations on related touchpoints, timespan, stakeholders, activities, experiences, emotions, and needs, as graphically represented in Fig. 1. The long-term sick leave phase is subdivided into four sub-phases (part 1–4) because of the long time span. The nine opportunities for improvement derived from the PEJM are highlighted at the end of the results section.

Working

The working phase, pre-sick leave, contains two paths: adapted working and fully working. The adapted working path presents patients who knew they had CVD, and adapted their work, e.g. hours or activities, in preparation for their scheduled surgery (see Fig. 1; touchpoints: adapted working, and activities). These patients decided on, and waited for, their surgery in consultation with their general practitioner and cardiologist (see Fig. 1; stakeholders and activities). During this phase patients experienced receiving work-focused advice from the cardiologist in preparation for the surgery to be positive (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs).

“I told the [cardiologist taking the intake for the surgery], I was working night shifts. And then he said: ‘You should stop [with working the night shifts], you just need to be in the best condition before surgery. (..) He explicitly gave me advice about [work].” – pt 9

However, to put work-focused advice from the cardiologist into practice, patients indicated the need for a flexible employer, and an accessible occupational physician, for the realization of work adjustments (see Fig. 1; stakeholders, positive experiences, and needs). The fully working path includes patients who reported no work adjustments because they had not yet experienced cardiovascular problems or were unaware of their underlying cardiovascular problem (see Fig. 1; touchpoints: fully working).

Short-term sick leave

All patients had a period of full-time sick leave at the onset of the cardiovascular event or the start of their medical intervention, e.g. surgery (see Fig. 1; touchpoints). Following this onset of sick leave, the occupational physician contacted the patients for occupational health consultation (see Fig. 1; touchpoints). A large share of the patients indicated that this first contact made by the occupational physician was too soon after the start of their medical intervention (see Fig. 1; negative experiences), highlighting the need for some time to focus fully on their recovery and accept their medical condition and bodily impairments (see Fig. 1; activities and needs).

“The week before [the appointment with the occupational physician], I had an angioplasty. (..) Then, you know, you’re sitting in front of [the occupational physician] and you can’t tell him anything useful yet.” – pt 2

Therefore, in this phase, patients indicated that they tried to avoid any formal contact with the employer and occupational physician (see Fig. 1; activities). Employers offering enough time to focus on recovery and postponing the consultation with the occupational physician contributed positively to this process of acceptance (see Fig. 1; positive experiences). Patients mentioned psychological counselling and a work-focused rehabilitation protocol to be important (see Fig. 1; needs). However, psychological consultation often was not provided, resulting in self-initiated psychological consultation later in time (see Fig. 1; stakeholders: self-initiated). In addition, patients expressed the need to understand their rights and obligations during sick leave (see Fig. 1; needs and negative experiences).

“At the moment you come home [after hospitalization], one of the most annoying things is that you are not aware of your rights [as an employee]. You do not know what is coming next and what you can do to stand up for yourself.” – pt 6

Long-term sick leave

Part 1—first few months

After approximately six weeks of sick leave, the first consultation with the occupational physician took place (see Fig. 1; timespan and touchpoints). The occupational physician supported patients in finding the optimal work position, matching their energetic limitations, and understanding the consequences for their functional work ability (see Fig. 1; activities). However, patients expressed the need for more medical knowledge, more tailored support in the interest of the patient, and no counterproductive pressure for vocational reintegration during consultation with the occupational physician (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs). Besides discussing future work ability with the occupational physician, patients indicated to highly value work-focused advice from their cardiologist (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs). Herefore, some patients asked for work-related advice from the cardiologist (see Fig. 1; activities and negative experiences).

“The cardiologist knows exactly what my diagnosis means. I like that, if I ask [my cardiologist] about what I can do [regarding work activities], you get an answer that you can rely on. You can take [the cardiologist’s] at his word.” – pt 1

According to the process of consultations, patients mentioned to value a clear information provision before, and feedback after consultation with professionals involved in their work-focused healthcare. In addition, the patients highlighted the need for transparency in the communication from their healthcare professionals towards the employer (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs).

“I would prefer to receive a summary [of the consultation with the occupational physician], including what we are going to do in the future, what [the occupational physician] is expecting, and his vision. I would really like to know that.” – pt 9

Part 2—towards the end of the 1st

year

The long-term sick leave phase continued with discussing work possibilities during routine occupational health consultations and 2nd line labor expert consultations, exploring alternative work positions outside the current job sector (see Fig. 1; touchpoints and activities). Patients experienced counterproductive pressure for vocational reintegration when the occupational physician put pressure on vocational reintegration too fast (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs). Besides, patients highlighted the need for specific guidance on how to overcome any work limitations (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs), since only answering the occupational physicians’ questions regarding work limitations and expectations were experienced negative (see Fig. 1; negative experience).

“You do not get any guidance, [the occupational physician] only asks you questions.” – pt 2.

In this phase, patients also expressed the need for clear information exchange between the occupational physician and cardiologist, for which the patients gave consent (see Fig. 1; activities). This information exchange was often experienced as insufficient due to long waiting times or incorrect information (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs).

“The occupational physician did ask the cardiologist [via a letter] about my diagnosis and what restrictions the cardiologist did impose on me. Then the cardiologist answered: ‘I did not impose any restrictions on the patient’. Which is true, the cardiologist did not do that, but my body did. But the occupational physician then was convinced I could work again.” – pt 10

Part 3—towards the end of the 2nd

year

When (full) vocational reintegration was not possible or successful, patients applied for a disability benefit at the SSA in collaboration with their employer towards the end of the second year of (partial) sick leave (see Fig. 1; touchpoints and activities). At this point, the need for a better understanding of the role of the stakeholders was mentioned (see Fig. 1; needs), since a lack of understanding is a bottleneck for the patients to properly prepare for the SSA trajectory (see Fig. 1; negative experiences).

“When applying for the disability benefit, at that moment I realized that I actually had no idea how the system works. (..) I felt like it would be useful at this point if I had a better understanding of which professional played with role in my process.” – pt 14

Following the application, patients were invited for disability evaluation by the insurance physician and the labor expert from the SSA (see Fig. 1; touchpoints). Patients identified being satisfied with the provided information about the upcoming consultations with the insurance physician (see Fig. 1; positive experiences). In case of any remaining questions, the need for a clear point of contact was highlighted (see Fig. 1; needs).

In addition, patients found it of great importance to have timely certainty on the outcome of the disability benefit assessment (see Fig. 1; needs). Planning the disability evaluation too late could cause a lot of uncertainty regarding future income (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and emotions).

“The decision [for the disability benefit] had not been made yet, while the two years of sick leave expired. So, that caused uncertainty.” – pt 15

Subsequently, patients searched continuously for their rights and obligations in preparation for, and during the disability evaluation process (see Fig. 1; activities). Therefore, patients regularly engaged stakeholders, such as a labor union, a lawyer or social counsellor, to provide legal support (see Fig. 1; stakeholders).

Part 4—after the 2nd

year

During the disability evaluation by the insurance physician working for the SSA, patients explained their functional limitations in daily life and participation due to their cardiovascular condition (see Fig. 1; touchpoints and activities). However, patients often felt insecure during consultation with the insurance physician, due to limited time, standardized protocols, and the feeling that the insurance physician was not sufficiently informed about their medical situation prior to the evaluation (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs).

“The insurance physician decides the percentage of work disability based on standard protocols. If you are a heart patient, they take a look in the protocol and it describes a percentage. It is the same for all heart patients. Which makes me wonder if they really assess the personal situation.” – pt 6

Subsequently, patients were informed about the decision regarding the disability benefit during consultation with the labor expert, and received a letter about the decision afterwards (see Fig. 1; touchpoints and activities). Patients highlighted lacking transparency in communication between the SSA and the employer regarding this decision (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs).

“But I do not know if my employer (..) received some kind of report [from the SSA about the decision of the disability benefit]. I have no idea, but I hope that was the case.” – pt 14

After granting the disability benefit (see Fig. 1; touchpoints), patients experienced a lack of information provided regarding the future disability benefit trajectory (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs). Besides, the need for someone to fall back on remained (see Fig. 1; needs).

Start vocational reintegration

When planning vocational reintegration, patients looked for a suitable work position matching their functional limitations supported by the labor expert, occupational physician, and eventually the reintegration coach (see Fig. 1; touchpoints, stakeholders, and activities). With the support of these stakeholders, a reintegration plan was created (see Fig. 1; activities), in which patients expressed their own decision-making to be important (see Fig. 1; positive experiences). Subsequently, patients consulted the reintegration coach and general practitioner to identify the boundaries in functional work ability and balance between working and private life (see Fig. 1; activities and stakeholders). However, finding a suitable work position could be difficult and employers did not always show flexibility and engagement by offering adjusted work positions (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs). When the employer lacked this flexibility and engagement, patients expressed the need for work-focused healthcare professionals to put pressure on the employer to stimulate to create a suitable work position (see Fig. 1; negative experiences and needs).

“I expected that the SSA would chase the employer [when the employer does not fulfill its obligations]. (..) But that did not happen.” – pt 13

Creating a suitable work position was followed by the first attempt at vocational reintegration (see Fig. 1; touchpoints).

Partial vocational reintegration

When the first attempt for vocational reintegration was successful, working hours were increased (see Fig. 1; touchpoints). Here, patients highlighted searching for a balanced vocational reintegration (see Fig. 1; activities), in which again the patients appreciated efforts by the employe, the occupational physician or the SSA to create a sustainable work position (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs). Also, patients indicated their functional boundaries to the employer and occupational physician, to protect themselves from any counterproductive pressure and prevent relapse to full-time sick leave (see Fig. 1; activities and negative experiences).

“Of course you have to indicate your barriers [to your employer], because every company only thinks about the money. (..) I just clearly stated what I have been through and what I’m feeling and when I want to start [working]. (..), and they [the employer] agreed with that. So, no pressure was put at me, which payed of because when I felt better I really wanted start working again.” – pt 18

Full vocational reintegration

When patients succeeded to build up working hours, the next and final step was full vocational reintegration (see Fig. 1; touchpoints). During this phase, patients could still not perform certain tasks due to chronic bodily impairments (see Fig. 1; activities). Therefore, patients mentioned an engaged and flexible attitude from the employer to be valuable (see Fig. 1; positive experiences and needs).

“[The employer] took the moments of stress during work away, by limiting my number of customers. (..) Furthermore, I do not lift heavy boxes by using special equipment for that. Those were the adjustments made [by my employer] to help me get fully back to work.” – pt 5

Patients felt insecure because no one was monitoring them while back at work (see Fig. 1; negative experiences), and expressed the need for someone to fall back on (see Fig. 1; needs and activities). Patients welcomed the offer from various stakeholders, e.g. the occupational physician, reintegration coach, or medical specialist, to contact them whenever needed (see Fig. 1; stakeholders and emotions).

“[The GP] said: ‘if there is anything, or you feel something, you can always call me’. That gives confidence, (..) That is just the support you need.” – pt 11

Opportunities for improvement to better meet the patient’s needs

Opportunities to improve work-focused healthcare from patients’ perspectives were identified throughout the various work-focused healthcare phases, based on the experiences and needs of the patients. Below, nine opportunities for improvement and their impact are presented in the order in which they appear in the PEJM (see Fig. 1, final row; opportunities for improvement).

Emphasize the need for work adjustment for faster recovery after medical intervention (phase: working):

Urging the need for, and supporting patients in, adjusting their work (work tasks and/or work environment) before medical intervention by involved professionals may contribute to a faster recovery and thus faster vocational reintegration.

Personalize the timing of the first consultation with the occupational physician (phase: short-term sick leave):

The large variety in the personal situation, and therefore, the timing of readiness to talk with occupational health professionals requests for adjusting the timing of the first consultation to the personal situation which may prevent the feeling of counterproductive pressure and rush.

Clarify the roles of the different stakeholders in advance (phase: long-term sick leave, part 1):

Improving information provision regarding the role of stakeholders towards the patients may facilitate less uncertainty and more autonomy at a later moment in time during the work-focused healthcare process.

Provide advice on how to handle work limitations (phase: long-term sick leave, part 2):

Offering the patients more specific tips on how to deal with their functional limitations during work, including tips regarding adjustments in work demands, working hours or workplace, may give the patients better ability and self-efficacy for vocational reintegration.

Put more compelling pressure on the employer to create a suitable work position (phase: start vocational reintegration):

Putting more pressure on the employers to offer opportunities for adjustments in work position, may facilitate a faster patient’s vocational reintegration.

Offer frequent check-in on abilities and boundaries (phase: partial vocational reintegration):

Offering more frequent check-ins with professionals to discuss work throughout the patient’s journey, supporting the search for a balanced reintegration and setting personal boundaries, may support the patient’s vocational reintegration.

Make sure a safety net is present (phase: full vocational reintegration):

Offering the patients the opportunity for continuity in support after full vocational reintegration or during the disability benefit, may prevent relapse and even potentially allow the patients to build up working hours further in some cases.

Provide timely information about the disability benefit trajectory (phase: long-term sick leave, part 3):

Clear and timely information on all process steps within the SSA trajectory, including the timeline of the disability benefit and reassessments, role of stakeholders and possibilities for reintegration support, may give the patients better knowledge of what to expect which can result in higher satisfaction levels.

Make the information flow towards the employer transparent for the patient (phase: long-term sick leave, part 4):

A more transparent information flow towards the employer, may give the patient more insight into, and a better understanding of, the employer’s actions.