Blood

Front Row Seat: Book chronicles Bob Dylan’s one, perfect Minnesota album session

DULUTH — On Friday, Dec. 27, 1974, two men from Hibbing met for the first time. Drummer Bill Berg carried his kit in from the bitter cold to set up at Sound 80 in Minneapolis, where he was booked for a recording session with Bob Dylan.

Did Dylan and Berg chat about their shared Iron Range history? About the fact that Berg had once seen Dylan, four years his elder, playing with Hibbing High School band The Golden Chords? About the fact that one of Berg’s cymbals came from Crippa Music, one of Dylan’s favorite Hibbing haunts? About the fact that Berg and his own band had rehearsed in the basement of

Dylan’s Hibbing house?

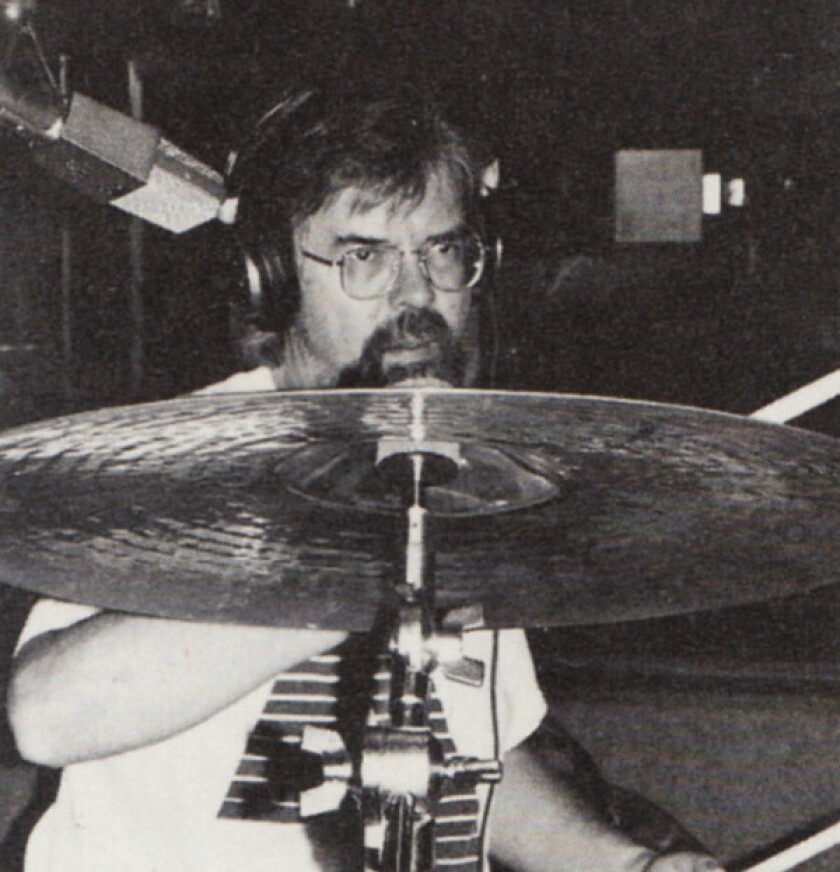

Contributed / Bill Berg

“Not one bit,” Berg remembered, as quoted in a new book about that recording session. “Bob does not ever do small talk, that I’ve ever heard. So it was only about the music, and hardly much about that at all.”

The new book, titled “Blood in the Tracks: The Minnesota Musicians Behind Dylan’s Masterpiece” (University of Minnesota Press), is co-authored by two Duluthians. Rick Shefchik grew up there, and wrote for the News Tribune for three years before becoming a St. Paul Pioneer Press journalist and, later, freelance writer. Paul Metsa, a singer-songwriter originally from Virginia, Minnesota, currently lives in Duluth — where, for a time, he

resided in the Central Hillside house

that Dylan first called home.

Much has been written about those two winter nights in 1974, including a 2004 book co-authored by Kevin Odegard, one of the musicians who played with Dylan. Still, “Blood in the Tracks” now stands as the definitive account of the sessions that produced one of the most lauded albums ever recorded in Minnesota.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the most recent version of

Rolling Stone magazine’s ranking of the greatest albums of all time,

Prince’s “Purple Rain” (partially recorded live at First Avenue, with other sessions at studios in Minnesota and on both coasts) comes in at number eight. Just one spot behind it is “Blood on the Tracks,” ahead of staggering works like “Blonde on Blonde” and “Highway 61 Revisited” as the most highly regarded LP by the only rocker to win a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Contributed / Columbia Records

It’s taken the Minnesota musicians who joined Dylan on that album a long time to get proper credit for their contributions. When the album hit stores in 1975, only the musicians who performed on the album’s initial sessions, in New York, were credited. To this day, as the authors note, standard issues of “Blood on the Tracks” still contain only credits for those artists. It took a deluxe reissue for the Minnesota performers to see their first official credits in association with the masterpiece.

Why? The Minneapolis sessions were a second thought. After recording in New York in fall 1974, Dylan had a fully complete version of the album ready for release. He wasn’t entirely happy with the tone of the New York sessions, though, and wanted to give one or more of the songs another try. His brother, David Zimmerman, assembled a band for what remains the only recording session in Dylan’s state of origin to become part of one of his official studio albums.

Five takes from the Minneapolis sessions made it onto the official release of “Blood on the Tracks,” intermingled with five takes from New York. The split nature of the sessions drew heat, if not light, for the Minnesota musicians. The starker New York sessions circulated as a bootleg, leading some influential fans to claim that the all-NYC version of “Blood on the Tracks” was better, that the “anonymous group of pickup musicians in Minneapolis,” as the book’s authors summarize this perspective, had softened the edges.

(The fact that Dylan himself rejected the New York takes in favor of the Minnesota recordings might have carried more weight in the case of a different artist, but the mercurial Dylan is infamous for leaving some of his best work in the vault while inexplicably releasing duds.)

Contributed / Barbara Odegard and Kevin Odegard

Even when the reissue “More Blood, More Tracks” was released in 2018, with dozens of outtakes and, at long last, accurate credits, the Minneapolis musicians got short shift — all the outtakes from the Sound 80 sessions were lost, so every alternate take included in the reissue was a New York recording.

“Blood in the Tracks,” the book, grew in part out of Metsa’s yearslong quest to elevate the musicians who played on those magical Minneapolis sessions. The authors’ take on the “New York did it better” argument is that a half-century of acclaim has vindicated Dylan’s own decision to re-cut some of his songs in Minneapolis. “Surely there isn’t much room for improvement,” they write dryly.

Readers who only want to know about what happened in the studio can skip to chapters 5 and 6, which detail the cozy confabs at what was then Minnesota’s latest and greatest recording studio. “The name was picked without realizing how quickly the ’80s would come up,” Sound 80 founder Herb Pilhofer says in the book.

ADVERTISEMENT

Metsa and Shefchik are at pains to bust two myths about the sessions — myths that may be particularly prevalent outside of Minnesota, where music fans are less likely to recognize the names of Dylan’s local collaborators. First, the authors point out that the musicians were hardly anonymous hacks. All were deeply respected musicians who knew each other, and have many other accomplishments under their belts.

Contributed / Bill Berg

Those accomplishments are the subject of chapters tracing the musicians’ backgrounds, and their post-1974 pursuits. Bassist Billy Peterson, for example, is an accomplished member of

a famed musical family

known for its close association with Prince. (Brother Paul’s band was the first to record “Nothing Compares 2 U.”)

Contributed / Jim Vasquez

In the decades following the Dylan sessions, guitarist Kevin Odegard became head of the National Academy of Songwriters. The late multi-instrumentalist Peter Ostroushko, who contributed mandolin to “If You See Her, Say Hello,” became bandleader for “A Prairie Home Companion.”

The other myth the authors set out to bust is the idea that Dylan turned to Minnesota musicians out of boredom or desperation. He was notably impatient during the New York sessions, barely communicating with the pros he shared the studio with and dismissing them from the sessions “like swatted bugs,” engineer Glenn Berger remembered.

In Minneapolis, by contrast, Dylan got in the groove and enjoyed a warm creative exchange with the band his brother brought together. He arrived at the studio with his son, Jakob, the future Wallflowers star who had just turned 5 years old. At one point, Odegard ran across the street to Skol Liquors to buy milk for the boy.

Contributed / Barbara Lundgren

It’s no surprise the Minneapolis sessions sounded warmer, with Dylan more engaged, than the New York sessions. While recordings from the two cities blended together nicely on the album, it’s the Minneapolis recordings that became the record’s tone-setting tentpoles.

“Idiot Wind,” the first song recorded at Sound 80, has a tortured lyric that gains humanity from the band’s sympathetic sound — without losing any of its bite. “If You See Her, Say Hello” opens up to become a symphonic paean. It’s the album’s opener, though, the strange and haunting “Tangled Up In Blue,” that became the record’s signature song and one of Dylan’s most beloved recordings.

“There was a great silence that came over the room and it lasted a while, because you couldn’t say anything after that,” said Odegard as quoted in the book, about recording that particular song. “The thoughts that were rolling through my head had to do with ‘Gee, if I ever have kids or grandkids, this is the moment I’m going to tell them about my music career.'”

ADVERTISEMENT

It was Dylan’s fellow Iron Ranger, Berg, who had the most unexpected journey following the “Blood” sessions. Trained as an illustrator, Berg pursued his dream of working at Disney and ultimately became a key animator during the studio’s renaissance in the late 1980s and early ’90s. He and his wife, a fellow animator, headed up the team that brought Ariel to life in “The Little Mermaid.”

Despite that remarkable film career, it’s “Blood on the Tracks” that Berg’s best known for. “I think we gave Bob’s music a little bit of grit and power that was not happening in New York,” Berg said as quoted in the book. It was Berg who drew the image that adorns the book’s cover, since no photos were taken during the Minneapolis sessions.

The song “Funkytown,” recorded five years later at Sound 80, is about leaving Minneapolis to find “a town that’s right for me.” For Dylan — if only for one, crucial album — that meant making a reverse journey and coming home to Minnesota.