Infection

How E. coli infections wreak havoc on the body, causing dangerous disease — particularly in kids

Escherichia coli, or E. coli, are a diverse group of bacteria. They typically thrive within the intestines of healthy animals. And, most of the time, they’re perfectly harmless.

But in some cases, certain strains are capable of causing severe disease, by rapidly spreading through the human digestive system, wreaking havoc throughout the bloodstream, and eventually damaging the delicate kidneys — leading to gruelling gastrointestinal symptoms, kidney failure and the potential for long-term health complications or death.

That’s the situation right now in Alberta, where a large E. coli outbreak linked to a shared kitchen in Calgary has sickened hundreds of daycare-aged children. There have been more than 260 lab-confirmed cases so far, and 25 patients are in hospital, the majority for a severe kidney disease known as hemolytic uremic syndrome.

So how did a common type of bacteria make this many children sick?

‘It’s an ongoing war’

“Bacteria are in our environment everywhere. And it’s an ongoing war,” said Edmonton-based intensive care physician and kidney specialist Dr. Darren Markland.

“And so certain bacteria have evolved advantages to be able to take over more territory, which is us.”

In the case of the Alberta cluster, which is already one of the largest E. coli outbreaks ever reported in Canada, the type hitting kids isn’t one of the typical strains that can cause several days of diarrhea, vomiting, cramps and other unpleasant gastrointestinal issues.

Instead, it’s a strain called O157.

This vicious pathogen is best known for sparking previous headline-making outbreaks, including the devastating Walkerton, Ont., tragedy in 2000.

In that instance, manure-tainted drinking water caused more than 2,300 cases and seven deaths — and a host of other smaller outbreaks linked to contaminated foods, ranging from packaged lettuce to salami.

E. coli spreads through gastrointestinal system

The O157 strain is found in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminating animals, such as cattle, but it doesn’t cause them any disease since their bodies don’t have the right receptors for this bacteria to tap into, said University of Guelph microbiologist Lawrence Goodridge, the director of the Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety.

But when people eat improperly cooked meat — or any items cross-contaminated by either raw meat or animal feces — this dangerous pathogen can enter the human body, starting an often-dangerous chain reaction.

The next stop is the stomach. Usually, the high acidity within that organ means most E. coli bacteria can’t survive, Goodridge said.

In the case of O157, however, he says ingesting just 10 of these single-celled organisms is enough to make someone sick.

Once this form of E. coli is in the gastrointestinal tract, it attaches itself to the inner lining — by latching onto epithelial cells, which cover various bodily surfaces — and then starts to multiply.

That growth process can produce nasty digestive symptoms, and marks the point where someone’s illness can take a dire turn. By the time O157 has reached the human colon, the longest part of the large intestine, it’s found a safe haven to lock in and build its army without being flushed out alongside everything else someone has ingested.

“E. coli doesn’t have to interact or compete with other bacteria there for nutrients,” said Melissa Kendall, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Virginia.

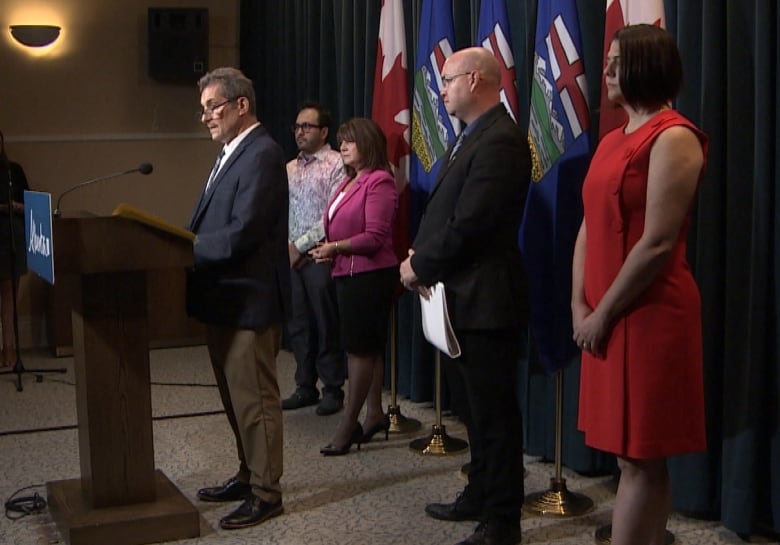

As the total number of E. coli infections associated with a chain of Calgary daycares climbs to 264, Alberta health officials say they are still looking for their specific source. However, health inspectors say they have found major issues with the facility, including cockroach infestations and unsafe food handling.

Kendall’s own research has explored a theory that this bacteria has a knack for seeking out the most oxygen-free crevices of the colon, allowing it to exploit its ability to activate specific genes once oxygen levels are low enough.

At that point, O157 is able to start producing a weapon known as Shiga toxin, thought by scientists to be one of the “most potent biological poisons.” That toxin can bind to a receptor on certain types of cells, burrow inside them, and lead to apoptosis, the scientific term for cellular suicide.

“We don’t fully understand all the cues that trigger or predict production of Shiga toxin, but it is the toxin … that’s being associated with this outbreak,” Kendall said.

And it doesn’t just stop at the colon. Markland, the kidney specialist in Edmonton, said Shiga toxin can spread throughout the human body, affecting every blood vessel.

Major impacts on kidneys

That’s particularly bad news for the kidneys — two bean-shaped organs below the rib cage, each the size of your fist — which work around-the-clock to filter blood, removing waste and extra water that’s eventually flushed out as urine.

“As a kidney doctor, I always tell my residents that kidneys are the most beautiful organs, but they’re incredibly delicate,” Markland said.

“They’re packed full of tons of very delicate blood vessels, and that’s in fact how they filter the blood.”

When they’re hit with something as potent as Shiga toxin, that hard-working pair of organs can start to struggle.

The process doesn’t happen all at once, Markland said: The initial E. coli infection comes first, followed by the Shiga toxin. About a week or so later, kidney damage starts to become clear. All the while, people may experience symptoms ranging from bloody diarrhea to painful abdominal cramps.

“If it’s severe enough, the kidneys will shut down,” said Markland.

That’s the dreaded hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, that nearly two-dozen children in Alberta are experiencing. It’s a condition impacting roughly 10 per cent of those infected — particularly kids — and often requires patients to go on dialysis, a treatment to clean someone’s blood when their kidneys aren’t functioning properly.

As of Tuesday, six patients who are part of the recent outbreak required dialysis at Alberta Children’s Hospital, CBC News previously reported.

Infectious diseases expert Dr. Isaac Bogoch explains why it’s important to understand the type of E. coli that’s causing an outbreak and why antibiotics aren’t always the right call.

During HUS, blood vessels are damaged, Markland said, which sparks a vicious cycle.

“They’re rough, they’re raw, they’re like sandpaper, so blood going through them gets torn up, and that tearing up propagates more damage downstream.”

Then, if the kidneys start to fully shut down, the body accumulates even more toxins.

“Once the damage is done,” Markland said, “all we can do is watch.”

Antibiotics and anti-diarrhea drugs aren’t effective, and might actually increase someone’s risk of developing HUS, by either fuelling toxin production or slowing movement through the gut, meaning someone is being exposed to toxins for a longer period of time.

There’s also no specific treatment to roll back kidney damage. Medical teams can only provide supportive care by helping manage patient symptoms and preventing dangerous dehydration.

In some cases, these infections can turn deadly, causing strokes or heart failure, but multiple experts told CBC News that most people, even those with serious cases, do recover.

Long-term health impacts

However, acute O157 infections — and the resulting damage — can take a lasting toll, particularly in vulnerable individuals with compromised immune systems, the elderly and young children, like those hit by the current outbreak.

“They can develop systemic complications, and in the case of E. coli O157, complications associated with the nervous system,” said Goodridge, from the University of Guelph. “Unfortunately, a food-borne infection, which is often mild for most people, can become a lifelong [illness].”

The permanent health impacts can include irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease, along with lasting kidney damage that can lead to early-onset high blood pressure or progressive kidney dysfunction, said Markland.

A follow-up study on the Walkerton tainted water disaster, for instance, found that 19 children who recovered from HUS still had after-effects close to a decade later, including excess protein in their urine and reductions in kidney function.

Scientists who’ve recently spoke to CBC News are now calling for similar patient follow-up, long-term investigations, and accountability for the Alberta daycare outbreak.

While the cause hasn’t been determined, officials recently announced that prior inspections of a centralized kitchen used by multiple daycares resulted in a series of major violations, from evidence of cockroaches to improper food handling.

And while the exact culprit may not be clear just yet, the potential health impacts are already well-known.

“We know that children are one of the risk groups for E. coli O157 — their immune systems are not fully developed yet — so it’s more difficult for them to fight off this infection,” said Goodridge.

“So I’m really concerned.”