Infection

In charts: Threat from infectious diseases eases across the world

Receive free Disease control and prevention updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Disease control and prevention news every morning.

Coronavirus brought the global threat of infectious diseases into sharp focus, but the broader picture is a positive one.

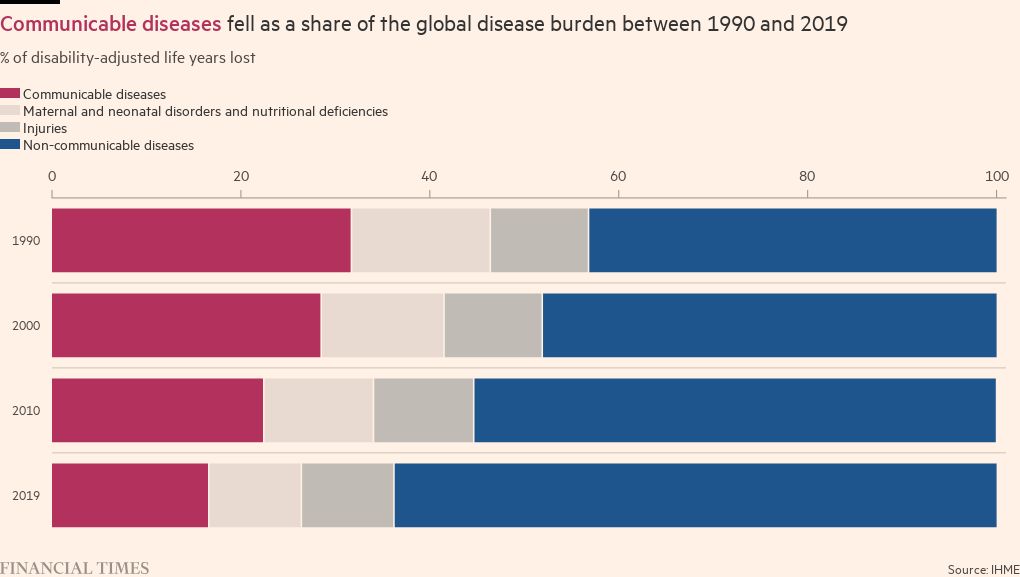

Communicable diseases, like malaria and tuberculosis, made up almost a third of the global health burden in 1990. But, in 2019, only a sixth of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost — a measure of lost healthy years of life — were the result of infectious diseases.

This is partly because of the rising burden from non-communicable illnesses, such as heart disease and cancer. But it is also due to global action through programmes such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which can help to bring down infection and mortality rates. Overall, the number of healthy years of life lost because of infectious diseases, when adjusted for population size and age, more than halved in the three decades to 2019.

Only a few infectious diseases were more deadly before Covid than they were in 1990, including HIV and invasive non-typhoidal salmonella — a bacteria that disproportionately affects people with HIV and malnourished children.

But, as both epidemics peaked in the 2000s, the picture looks more positive over a shorter timeframe. At a global level, hardly any infectious disease caused a notable increase in DALYs between 2010 and 2019.

Most countries experienced a decline in the communicable disease burden. Dr Haidong Wang, unit head for monitoring, forecasting and inequalities at the World Health Organization (WHO), points to the declining burden from HIV as one reason for this transition. “Through concerted efforts by countries and the international community, we can actually decrease the burden of specific diseases, especially infectious ones,” he says. Even in Africa, where there was a “disproportionately large” burden from HIV, substantial progress has been made, he adds.

However, HIV is still a major problem in some parts of the continent. Three of the four countries where age-adjusted DALY rates increased between 1990 and 2019 were African nations, with some of the world’s highest rates of HIV.

The worst affected place was Lesotho, a country landlocked by South Africa, where DALY rates from communicable disease doubled over this period.

Its situation reflects a broader divide between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world. As well as facing the worst of HIV, in the three decades to 2019, the region had the highest rates of DALYs lost from other sexually-transmitted diseases as well as respiratory infections.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the only part of the world where these kinds of illnesses were still a significant contributor to the overall burden of ill-health in 2019. Infectious diseases made up 44 per cent of DALYs lost in the region, compared with 18 per cent in South Asia, which had the next highest share.

Wang says the region is at an earlier stage of its demographic and epidemiological transition from high to low mortality and fertility rates than elsewhere. “Infectious diseases tend to account for a much higher proportion of the disease burden at the initial stages of the transition,” he says. “Over time, it shrinks and non-communicable disease increases. Most countries in Africa are still in that transition period but, over the next few decades, we would expect the communicable disease burden to decrease.”