Blood

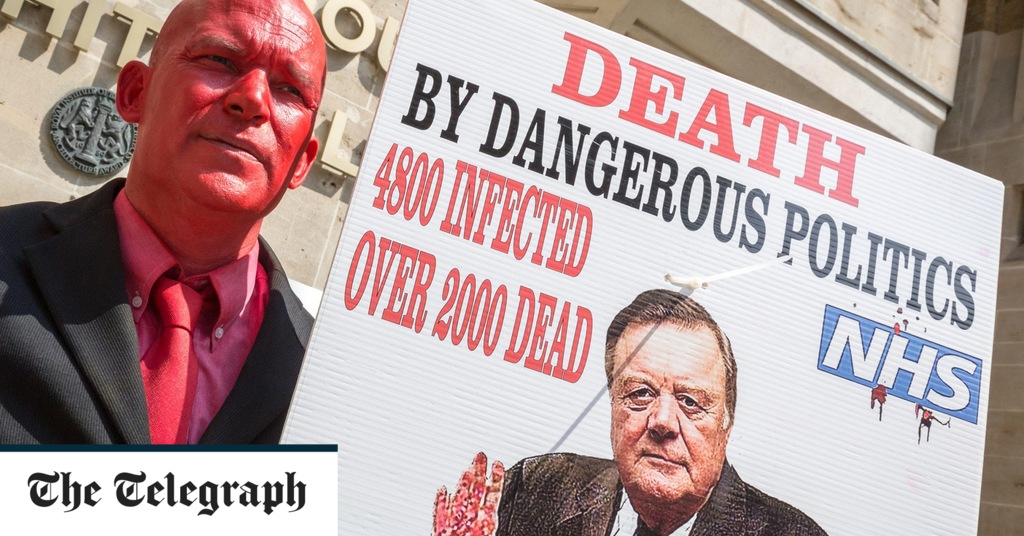

The horrific story of infected blood in the NHS (and beyond)

Lord Mayor Treloar College in Hampshire, founded in 1907 for the education and care of physically disabled children, was more than just a school. When Ade Goodyear was there in the early 1980s, the teaching and medical staff seemed like an extended family. Dr Anthony Aronstam, director of the college’s haemophilia centre – the condition for which Goodyear was receiving treatments derived from processed blood – would invite Goodyear and his schoolfriends over to Aronstam’s house: the boys would drink lemonade and swim in the pool.

One summer afternoon in 1984, however, Goodyear found Aronstam bent over his desk and trembling. “We’ve f—-d up,” Aronstam said. “I’ve messed up. It’s all gone wrong.” In the face of a gathering global calamity, Aronstam had been assessing Goodyear, without his knowledge, for signs of Aids. Two of Goodyear’s peers had been diagnosed; one had already died. By 1986, Aronstam had 43 young patients who were HIV-positive, and he wrote in a report of “gloomier predictions” suggesting that “up to 100 per cent of the infected haemophiliac population will eventually succumb to the virus.”

The Poison Line is the first book by journalist Cara McGoogan. It began life as a set of features written for this newspaper in 2019, during the opening week of the Infected Blood Inquiry, but has become the story of a global medical scandal, implicating health services, pharmaceutical companies and whole governments, and unfolding slowly enough, and meeting obstacles enough, that many of its victims died before they ever saw justice, never mind compensation.

It is told, for the most part, through the recollections of the victims, their families, their doctors and their legal and political representatives. That so many individual stories in The Poison Line burn into the reader’s skull is testament to the strength of the source material. Lord Mayor Treloar College is just the most familiar domestic emblem of a crisis that played out across America, Britain, mainland Europe and south-east Asia.

It began when a new, much quicker, more convenient and more comfortable way was found of administering blood-clotting factors to haemophiliacs. Factor VIII, a freeze-dried powder derived from blood, was infected with hepatitis B, but since this infection was common among haemophiliacs anyway, and went away in time, the issue was ignored. Consequently, other agents infecting Factor VIII went undetected, including HIV and hepatitis C. Institution after institution then doubled down on their original error.