Blood

Why the President of Iran Does Not Deserve Dialogue

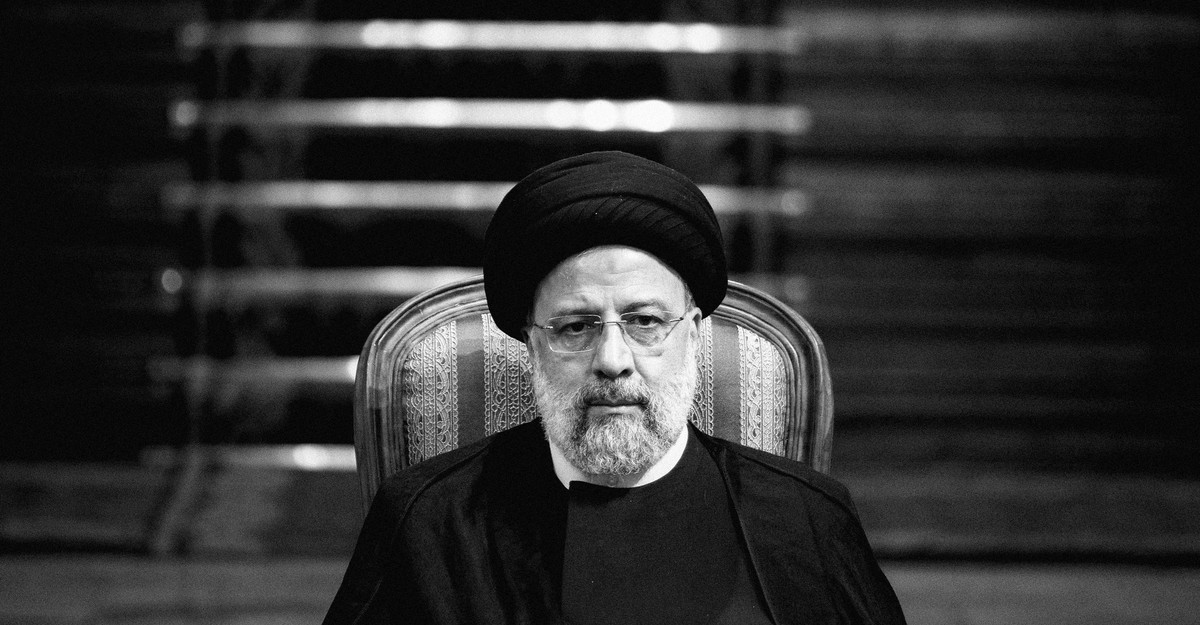

Last week, the Council on Foreign Relations invited me to a roundtable discussion it will be hosting Tuesday with the president of Iran, Ebrahim Raisi, who will be in New York for the United Nations General Assembly. As a longtime member of the council, I wrote back to decline the invitation and published a brief statement about why I believe that Raisi, a man who ought to be behind bars for mass murder, must not be accorded this legitimacy.

Last year, a court in Sweden found a prison official guilty of war crimes in one of the worst atrocities ever committed in the history of modern Iran. That verdict directly implicated Raisi, who was a central enforcer of the policy of exterminating prisoners of conscience, which resulted in thousands of executions carried out over about five months starting in July 1988. This judicial finding mirrored the result of an earlier prosecution in Germany, where a court ruled that Iran’s top leaders were responsible for the state-sponsored assassination of four regime opponents in Berlin in 1992.

I spent four years researching a book about that case, which set this vital precedent: In response to the judgment, all but one member of the European Union withdrew its ambassador from Tehran (as did Canada). The diplomatic blackout delivered a grave blow to the regime, forcing Iran to end its efforts to eliminate dissidents and opponents in the West for more than a decade. After that, none of Iran’s leaders whom the presiding judge said had “ordered the crime,” including the late President Hashemi Rafsanjani, ever set foot again in the EU.

In an email to me, the CFR’s president, Michael Froman, wrote that “over the decades, CFR has hosted numerous leaders representing governments with policies many members and most American citizens objected to,” but that “a dialogue of this kind is consistent with CFR’s longstanding tradition and mission” and does not “represent an endorsement or approval of a government or its policies.” He also pointed out that “other Iranian leaders who have spoken at CFR include the shah of Iran in 1949 and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2006.” Although Ahmadinejad’s invitation was controversial at the time because of his record of Holocaust denial, I have no argument with Froman on that invitation. As reprehensible as Ahmadinejad’s views are, no court has fingered him as a mass murderer. There is an important distinction between Ahmadinejad, who denies an evil, and Raisi, who has committed one.

That is a distinction that I believe the Council on Foreign Relations should make. Even though it is not a government, the council relies on American democratic values and the rule of law in delivering its mission of promoting dialogue. If one Iranian president, Rafsanjani, was declared an international persona non grata by Western allies for his part in state killings in the German precedent, then another Iranian president, Raisi, should be accorded the same treatment by virtue of the Swedish case.

In 1988, the then-supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa that ordered the killing of thousands of prisoners of conscience. The job of carrying out that fatwa fell to four regime officials who made up what is now commonly known as the “death committee.” Raisi, Iran’s deputy chief prosecutor at the time, was one of them. Within a few weeks, an efficient killing machine was set up at several major prisons throughout the country. Prisoners were interrogated about their religious views: whether they believed in God, Islam, the Prophet Muhammad; whether they prayed; and so on.

Although the majority of the prisoners had already stood trial and received custodial sentences, their fate now depended on how they responded to the questions. One negative answer to any of the questions sent them to the gallows. The dead, estimated to number at least 2,800 and perhaps as many as 5,000, were covertly buried in mass graves. Some families went to the prisons expecting to pick up their loved one whose sentence was up; instead, they were handed a bag containing their loved one’s few belongings. All families were denied the right to hold a funeral, lest the grieving crowd turn angry and riotous.

The executions caused a permanent rupture between Khomeini and the cleric he had named as his successor, Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri. When Montazeri received the news of the fatwa, he wrote two scathing letters to Khomeini, describing the act as “malicious” and “vengeful.” A third letter was addressed to the members of the death committee, including Raisi, calling their work “mass murder.” When he met with them, he told them, in a chilling recording that has since become public, that they would “go down in history as criminals.”

Montazeri’s dissent ultimately cost him the succession, which went to a far more hard-line cleric, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who still holds the post. Great evils have a way of changing the course of a nation’s history. The 1988 massacre did that for Iran.

In 2019, the Swedish authorities, through the exercise of the law of universal jurisdiction, arrested a former Iranian prison guard named Hamid Nouri, who had worked for the death committee. Some of the witnesses of that bloody summer were finally able to testify at Nouri’s lengthy trial and feel that a modicum of justice had, at last, been served. At its conclusion, in July 2022, the court found Nouri guilty of participating in the mass killings. For his part, 35 years later, Raisi boasts of his role in them, declaring the atrocity “praiseworthy” and necessary for “the nation’s security.”

When Western nations have joined together to deliver a firm message to Tehran, the clerics, however recalcitrant, have backed down. Just such a powerful show of unity came at the conclusion of a comparable trial, in April 1997, in Germany. Several Iranian and Lebanese members of the Hezbollah militia were accused of carrying out the assassination of three Iranian-Kurdish leaders along with another Iranian opposition figure at a Berlin restaurant. In their verdict, the judges found Iran’s senior leadership—including the supreme leader, the president, and the foreign minister—responsible for the crime. Earlier in the trial, the court had issued an arrest warrant for the intelligence minister, Ali Fallahian, who has since been on Interpol’s wanted list. I later interviewed the German attorney general, Alexander von Stahl, who had overseen the case. He had not, he said, been “willing to let his homeland become the playpen of thugs.”

If democracy is to survive the current wave of authoritarianism, Western nations must band together to uphold the rule of law. Sweden showed the way last year. Once, America led the establishment of modern democracy as we know it; today, it needs to show that sustaining democracy depends on a collective defense of its laws and judicial decisions. That means exercising an equal commitment to upholding dialogue with our adversaries and ending dialogue with those who are recognized as outlaws. So I do not believe that the Council on Foreign Relations, in this context, can stand to one side and claim that its invitation does not confer endorsement or approval: It does confer legitimacy, by treating this criminal as a reasonable interlocutor.

As the philosopher Karl Popper warned: “If we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.” To invite Raisi to one of our most prestigious venues, to let him sit among us, and to listen courteously to what he has to say would be to let him think he has gotten away with murder. And he would be right.