Infection

Deadly hospital infections have a mysterious trigger

Hospitals have always been at the forefront of infection prevention. Now, a study from Michigan Medicine suggests that some of the most common hospital infections are not spreading the way we thought.

Hospital infections

Every year, nearly half a million Americans become infected with Clostridioides difficile, more commonly known as C. diff. Hospitals use many precautionary measures – from rigorous hand hygiene practices to specialized isolation rooms – to prevent these infections.

The new research, published in the journal Nature Medicine, suggests that these hospital-onset infections may not be primarily due to hospital transmission as previously believed. Instead, the primary cause could be patient-specific characteristics.

The study was led by Dr. Evan Snitkin and Dr. Vincent Young of the University of Michigan Medical School and Dr. Mary Hayden of Rush University Medical Center.

Focus of the study

The team analyzed data from ongoing studies focused on hospital-acquired infections. This allowed them to closely monitor every patient in Rush University Medical Center’s ICU over nine months, collecting daily fecal samples.

What the researchers learned

Of the 1,100 patients observed, study co-author Arianna Miles-Jay discovered that just over 9% were carriers of C. diff.

However, when these strains were genetically sequenced and compared, an unexpected pattern emerged: these infections weren’t spreading from patient to patient within the hospital at the rate previously assumed.

Only six instances of genomically supported transmissions were identified over the entire study duration. This means that the vast majority of infections weren’t acquired from the hospital environment or from other patients.

An unknown trigger

Dr. Snitkin summarized the team’s surprise, stating that something still unknown triggers C. diff to transition from a dormant state in the gut to an active infection.

“By systematically culturing every patient, we thought we could understand how transmission was happening. The surprise was that, based on the genomics, there was very little transmission.”

“Something happened to these patients that we still don’t understand to trigger the transition from C. diff hanging out in the gut to the organism causing diarrhea and the other complications resulting from infection,” said Dr. Snitkin.

Prevention measures

This doesn’t invalidate current hospital infection prevention measures. Dr. Hayden emphasized that the strict precautions at Rush ICU likely contributed to the low in-hospital transmission.

Yet, the study indicates the necessity for additional measures, especially for identifying and safeguarding colonized patients.

Where does C. diff come from?

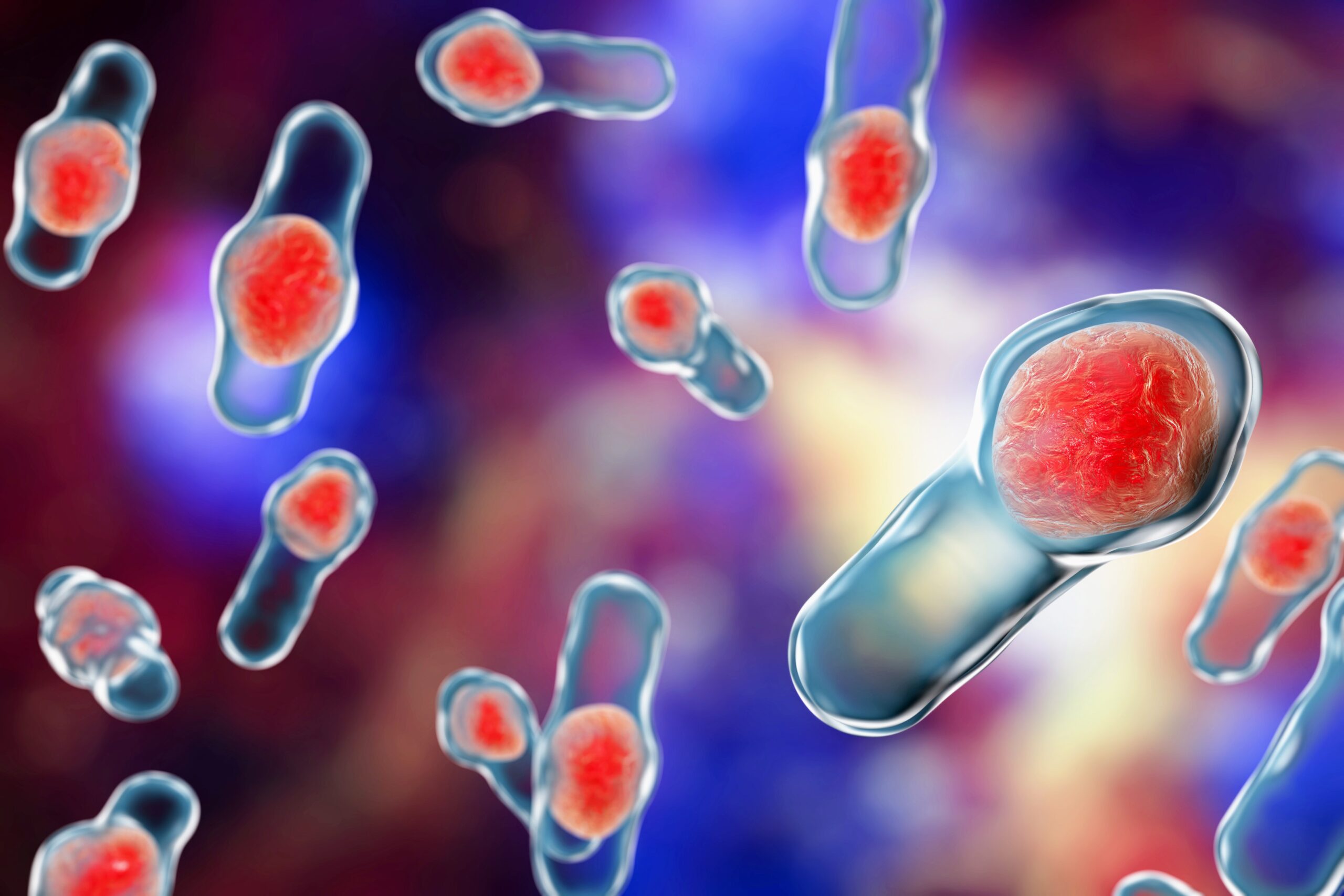

C. diff is more common in our surroundings than one might think. “They are sort of all around us,” said Dr. Young. “C. diff creates spores, which are quite resistant to environmental stresses including exposure to oxygen and dehydration…for example, they are impervious to alcohol-based hand sanitizer.”

However, only about 5% of the population outside of a healthcare setting has C. diff in their gut – where it typically causes no issues.

“We need to figure out ways to prevent patients from developing an infection when we give them tube feedings, antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors – all things which predispose people to getting an actual infection with C. diff that causes damage to the intestines or worse.”

Future research

The team’s findings suggest a paradigm shift in approach. As Dr. Young noted, the next challenge is to discern how common medical practices, such as antibiotics or tube feedings, might inadvertently activate a C. diff infection.

Moving forward, the research team plans to use artificial intelligence to predict which patients are most at risk. By redirecting some resources, they hope to not only prevent infections but also optimize medical procedures and identify potential triggers for these infections.

“A lot of resources are put into gaining further improvements in preventing the spread of infections, when there is increasing support to redirect some of these resources to optimize the use of antibiotics and identify other triggers that lead patients harboring C diff and other healthcare pathogens to develop serious infections,” said Dr. Snitkin.

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

—-

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.