Infection

Nipah virus outbreak: what scientists know so far

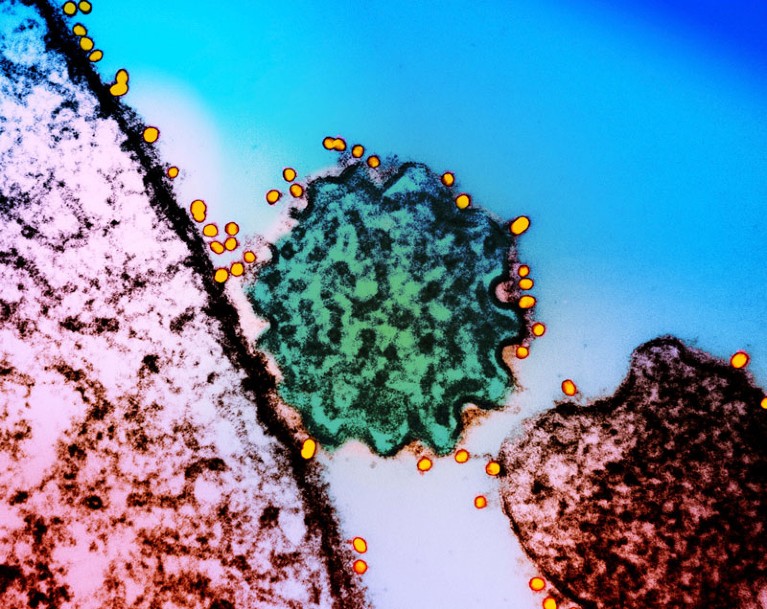

Nipah virus (green) can be deadly.Credit: National Institutes of Health/Science Photo Library

In the southern Indian state of Kerala, the bat-borne Nipah virus has infected six people — two of whom have died — since it emerged in late August. More than 700 people, including health-care workers, have been tested for infection over the past week. State authorities have closed some schools, offices and public-transport networks.

The Nipah outbreak is the fourth to hit Kerala in five years — the most recent one was in 2021. Although such outbreaks usually affect a relatively small geographical area, they can be deadly, and some scientists worry that increased spread among people could lead to the virus becoming more contagious. Nipah virus has a fatality rate between 40% and 75% depending on the strain, says Rajib Ausraful Islam, a veterinary physician who specializes in bat-borne pathogens at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, in Dhaka. “Each outbreak is a concern,” he says. “Every outbreak is giving the pathogen an opportunity to modify itself.”

The virus can cause fever, vomiting, respiratory issues and inflammation in the brain. It is carried mainly by fruit bats, but can also infect domestic animals such as pigs, along with humans. It spreads through contact with bodily fluids from infected animals or people. There are no approved vaccines or treatments, but researchers are investigating candidates.

Occasional outbreaks

Nipah virus was first detected in 1998, during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia. Within months, it had spread to Singapore through infected pigs. The outbreak resulted in nearly 300 cases and more than 100 deaths.

Since then, no other outbreaks of Nipah virus have been reported in Malaysia. But in 2001, the virus emerged in Bangladesh and India, where outbreaks have continued to flare up periodically. In Bangladesh, outbreaks occur almost every year, and studies have linked infections with drinking date-palm sap contaminated with bat urine1. It’s unclear exactly when and how the virus jumped from bats to people in the current Kerala outbreak, but scientists are investigating.

The strain circulating in India and Bangladesh is different from the one that surfaced in Malaysia, says Stephen Luby, an epidemiologist at Stanford University in California. Whereas the Malaysia strain spread from animals to humans, there was little transmission between people. But the version that’s behind the latest outbreak in Kerala can be passed from person to person, and is much deadlier. “It does remind us that this is a nasty virus”, says Luby.

Health workers transport a person with symptoms of Nipah virus infection in Kerala, India.Credit: AFP/Getty

Despite its potential to kill, Nipah virus doesn’t spread as easily between people as other animal-borne infections do, making it less likely to spread beyond country borders, says Danielle Anderson, a virologist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia. A 2019 study of nearly 250 Nipah virus cases in Bangladesh over 14 years found that roughly one-third of infections were caused by person-to-person transmission2. “I would not expect that it would spread globally,” says Anderson. “Nothing to the extent of what we’ve seen with COVID-19.”

The virus’s high fatality rate also gives it less opportunity to spread rapidly through populations, says Christopher Broder, who specializes in emerging infectious diseases at the Uniformed Services University Medical School in Bethesda, Maryland. “It’s not in the virus’s best interest to kill everyone it infects.” He adds that the strain circulating in Kerala has not changed much since it first emerged more than two decades ago in Bangladesh, although future outbreaks could be bigger if it mutates into a milder but more contagious strain. There are also likely to be variants already circulating that haven’t been detected yet, says Broder.

Managing bats

A key step in preventing outbreaks of Nipah and other bat-borne viruses is developing better ways of managing wildlife that lives close to communities, says Andrew Breed, a veterinary epidemiologist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. Studies on Hendra virus — another bat-borne pathogen that’s closely related to Nipah — suggest that infected bats shed more virus particles when they’re stressed, increasing the chance that the disease will spill over into humans, says Breed. One approach that could go a long way towards heading off future outbreaks is to restore forest areas to provide more habitat for bats, which would keep them at a safe distance from humans, says Breed.

Another way to reduce the risk of bat-borne diseases spreading to humans is to plant more trees that produce fruit that is appetizing to bats but not to humans, says Islam. This could help to keep infected bats from contaminating food. “We need to learn how to live safely with bats,” he says.