Infection

Texas has the most ‘brain-eating’ amoeba infections in the U.S. Here’s what to know

Every summer, you see the same kind of headline: “Person dies from a ‘brain-eating’ amoeba.” You probably scroll through the article, shudder a bit, think twice about going swimming and move on.

But this summer, that headline hit closer to home. A Travis County resident was infected and killed by the amoeba, Naegleria fowleri, after swimming in Lake LBJ in August.

If you were spooked, you weren’t alone. Austin is a city of swimmers, and we’re lucky to have an abundance of nearby natural springs, pools, lakes and rivers. Swimming has also been a refuge for many during a season of record-breaking heat.

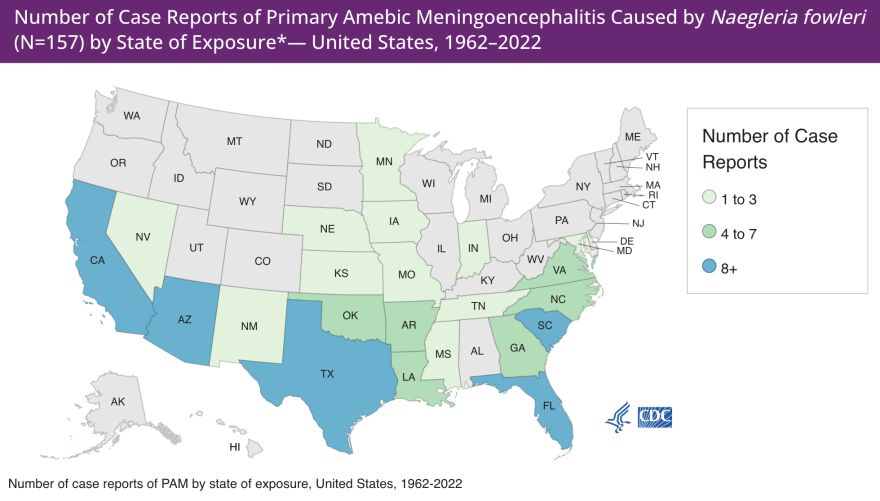

It doesn’t help that Texas has the greatest number of reported cases out of any state, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — a total of 40 since 1962. (The CDC site reports 39 cases up to 2022; Texas Department of State Health Services confirmed the recent Travis County infection is the only case it has encountered in 2023.)

KUT spoke to three experts about how dangerous Naegleria fowleri is and what you can do to protect yourself. Here’s what you need to know.

What exactly is this ‘brain-eating’ amoeba?

Naegleria fowleri is an amoeba (aka a single-celled organism) that usually lives in warm, fresh bodies of water and soil. It thrives in water temperatures of around 80 to 115 degrees, which is why infections happen more often in Southern states and during the summer.

Austin’s scorching temperatures these past couple months have unfortunately made it a great place for Naegleria fowleri to hang around.

“In our area, we’ve had over 70 days with severe heat advisories, so that’s made it the perfect situation for the development of stagnation in the water and growth of things like this amoeba,” said Dr. Desmar Walkes, medical director of Austin Public Health and health authority for Austin-Travis County.

As its nickname suggests, the “brain-eating” amoeba infects people by traveling up the nose, through a layer of bone, and up to the olfactory bulb, which is responsible for sending smell signals to your brain. From there, Naegleria fowleri “literally is going to eat the cells of the olfactory bulb and what’s called the cortex of the brain,” said David Siderovski, a pharmacology and neuroscience professor at the University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth.

The resulting infection is called primary amebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM. PAM destroys cells and blood vessels in the brain, leading to bleeding, swelling and, in more than 97% of cases, death. Only four people in the U.S. are known to have survived PAM.

Symptoms start one to 12 days after exposure and include severe headache, fever, nausea and vomiting, according to the CDC. As PAM progresses, it can cause neck stiffness, seizures, hallucinations and coma. People can die anywhere from one to 18 days after symptoms start.

The reason the disease is so deadly, Siderovski said, is because it shares symptoms with another infection, bacterial meningitis, and often gets misdiagnosed. Testing for Naegleria fowleri is also a slow process, and there are no drugs specifically made to kill the amoeba.

“By the time you diagnose, the only thing you have to treat [it] are drugs from other illnesses,” Siderovski said.

That all sounds terrible. How worried should I be about getting infected?

There’s good news and bad news. The bad news: Naegleria fowleri is basically everywhere.

“We should assume that all Texan freshwater sources — our lakes, our rivers, the Brazos, the Rio Grande, et cetera — we should assume that we have it all the time,” Siderovski said.

It’s so common that the CDC advises against putting up signs warning swimmers of the amoeba — because it might give the false assumption that a lake or river without a sign is fowleri-free.

The good news is that even though the amoeba is common, PAM is rare. Texas saw zero, one or two cases each year from 2010 to 2023, said Johnathan Ledbetter, a manager with the Emerging and Acute Infectious Disease Unit at Texas DSHS. That’s out of hundreds of thousands of people who swim in Texas’ fresh waters every year.

And since Naegleria fowleri has to go pretty far up the nose to infect the brain, you don’t have to worry about getting sick just by being around, touching or even drinking contaminated water. The real risk comes from putting your head underwater, especially if you’re diving and pushing water farther into your nose, Siderovski said.

In even rarer cases, people have gotten PAM from swimming in improperly chlorinated pool water or rinsing their sinuses with contaminated tap water for health or religious reasons.

To lower the risk of PAM across all of these scenarios, Ledbetter recommends that you:

- Avoid going in fresh water when the weather is hot and water levels are low.

- Hold your nose, use nose clips or keep your head above water while swimming.

- Avoid kicking up the dirt at the bottom of shallow swimming areas.

Back to the temperature thing. Texas is getting hotter. Is that good for the amoeba (and bad for us)?

There’s research that suggests Naegleria fowleri is spreading farther north because of rising temperatures. While Siderovski hasn’t seen any studies on how climate change might affect PAM in Texas, which already sees a consistent number of cases, he thinks it’s possible infections could start occurring outside of the usual “peak” months of July, August and September.

“You can speculate that the longer the summer has those high, 110-plus degree days, the broader that cluster of months where the risk is high is going to extend,” he said. “I can imagine that we’re going to see an extension, especially [considering] the summer we’ve had, out to October and beyond.”

But he also believes that more people taking preventative measures could curb or even decrease PAM. And Walkes at Austin Public Health points out the swimming practices that protect you from PAM help prevent other water borne illnesses, too.

“Stagnant water is a breeding ground for lots and lots of microbial organisms,” she said. “We know that we have a drought. We know that we have stagnant water. And those are places where you need to make sure you are taking precautions.”

Copyright 2023 KUT 90.5. To see more, visit KUT 90.5.