Congenital disorders

The difference between two brachycephalic and one mesocephalic dog breeds’ problem-solving performance suggests evidence for paedomorphism in behaviour

Abstract

Despite serious health and longevity problems, small brachycephalic breeds are becoming increasingly popular among pet owners. Motivations for choosing short-nosed breeds have been extensively investigated in recent years; however, this issue has been addressed mainly by relying on owner reports, resulting in explanations of “cute looks”, referring to the baby-schema phenomenon and “behaviour well suited for companionship”. We aimed to compare the behaviour of two brachycephalic (English and French bulldogs) and one mesocephalic (Mudi) breed in a problem-solving context. The dogs were given the task of opening boxes containing food rewards. We investigated human-directed behaviour elements over success and latency (indicators of motivation and ability). We found that both English and French bulldogs were significantly less successful in solving the problem than mudis. Both brachycephalic breeds had longer opening latencies than the mesocephalic breed. Brachycephalic breeds oriented less at the problem box and more at humans present. In summary, the short-headed breeds were less successful but oriented much more toward humans than mesocephalic dogs. Owners might interpret these behaviours as “helplessness” and dependence. The results support the hypothesis that infant-like traits may be present not only in appearance but also in behaviour in brachycephalic breeds, eliciting caring behaviour in owners.

Introduction

Short-headed, flat-faced, small companion dog breeds (so-called small brachycephalic breeds) are becoming increasingly popular among dog owners1,2,3,4,5, even though brachycephalism is associated with a range of serious health and welfare issues3,6,7,8. This puzzling phenomenon could be described as the “Flat-Faced Paradox”. Despite the efforts to raise awareness of future owners, currently, the French bulldog is the second most popular breed in the UK and the USA1,9 and first in Hungary10, while other flat-faced breeds are also among the top popular breeds, e.g. the English bulldog, the Pug, the Boston terrier and the Shih Tzu. Brachycephalic breeds tend to suffer from breathing problems (such as brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome—BOAS e.g.11), eye diseases e.g.12, spinal malformations/neurological issues e.g.13,14, brain disorders3, sleeping disorders e.g.15, skin3, ear and dental diseases3, gastrointestinal disorders e.g.16,17, thermoregulation problems e.g.18, exercise intolerance6, and above all, have difficulties giving birth naturally e.g.19. Furthermore, mostly because of their health problems, small brachycephalic breeds have a considerably shorter expected lifespan than their longer-headed counterparts3,20,21. Nonetheless, some owners still are highly likely to reacquire (93%) these breeds and recommend them to prospective owners (65.5%)22. High levels of health problems can even positively affect the owner-dog attachment23.

The main reasons reported by owners are that these breeds are supposedly suitable for households with children, well suited for a sedentary lifestyle and display positive behaviour traits for companionship, the latter being a key factor24. While no evidence has been found that these breeds have a lower risk factor for biting children25, no doubt that they are suitable for a sedentary lifestyle, as they have been shown to suffer from excessive exercise intolerance26,27. However, the reported “positive behaviour traits for companionship” are worth further investigation, as various interesting behavioural differences between brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic breeds have been identified. For example, dogs with higher cephalic indexes (brachycephalic or “short” headed) have been found to be more successful in following the human pointing gesture than dogs with lower cephalic indices28. Brachycephalic breeds display longer looking times at human and dog portraits compared to longer-headed breeds29. Shorter-headed dogs also have been shown to establish eye contact with humans more readily than longer-headed dogs30. Moreover, positive behaviours directed toward unfamiliar humans, such as being affectionate, cooperative and interactive, are associated with a higher cephalic index31,32. These findings support the hypothesis that not only the “cute”, paedomorphic appearance33 but behaviour characteristics (due to genetic predisposition or the result of different treatment) indeed might influence the choice of this breed and the development of breed loyalty.

Paedomorphic (baby-like) appearance, in general, triggers a nurturing, caring instinct across species (baby-schema effect) see e.g.34,35,36. Paedomorphic facial attributes have been found to enhance the chance of adoption in both cats37 and dogs38. Owners also infer the personality of dogs and expected relationship quality based on physical appearance39.

However, baby-like traits may also be present in behaviour. Dogs, in general, display such behaviours that elicit care40,41,42, but breeds with a more baby-like appearance could also be more prone to display “helpless”, baby-like, care-inducing behaviours compared to breeds with a longer head shape.

In an unsolvable task paradigm, dogs, but not wolves, have been found to look back at humans43, which has been widely interpreted as a communicative, perhaps even “assistance seeking” intent (but also see44), or as an indicator of generalised dependence on human action45. Whichever the case, looking back at the human in an independent problem-solving task is most probably interpreted by the human counterpart as help-seeking or at least a sign of helplessness, which may trigger the nurturing instinct. While differences in looking back behaviour in an independent problem-solving context may be mediated by various factors, such as life experience, training history46,47,48,49 or anxiety-related disorders50, we suggest that such context may still be suitable to study differences in care-inducing behaviours.

In this study, we aimed to compare two brachycephalic and one mesocephalic breeds’ behaviour in three similar independent problem-solving tasks, slightly differing in difficulty. We not only wanted to compare success rates but also, more importantly, wished to check for differences in human-directed behaviour and thus search for evidence of paedomorphic behaviour traits, which may be appealing to present and prospective owners.

Method

Subjects

We assessed 15 English bulldogs [10 males, 5 females, age range 0.75–9.92 years (average. 3.71 years)], 15 French bulldogs [5 males, 10 females, age range 0.67–7.00 years (average 2.34 years)], and 13 Hungarian mudis [7 males, 6 females, age range 1.50–11.00 years (average 4.29 years)] in behaviour tests. All subjects from all three breeds were recruited similarly. Owners were approached on annual meetings of the breed (so called Breed Meet Days), where they were asked if they are willing to volunteer for a behaviour test. If they agreed to do so, they were informed about the procedure and asked to sign a consent form before the experiment started.

Equipment

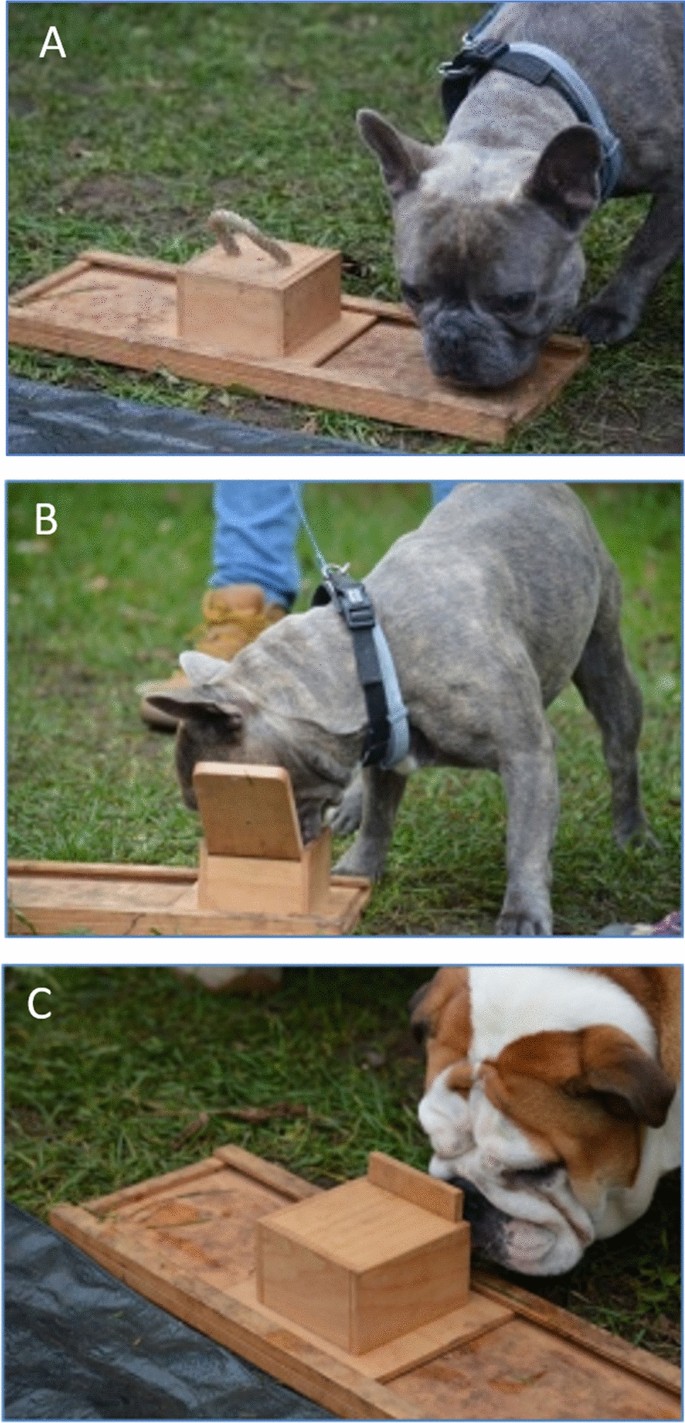

We have used three commercially available problem boxes intended for dogs (Games4Brain Dog Intelligence Game Set), made of plywood, all mountable to a 50 cm long plywood rail to prevent knocking over. All boxes had a different opening technique, growing in difficulty, with Box A being the most difficult to open and Box C being the easiest. Please see Fig. 1 for the pictures of the boxes and the opening technique.

Illustration of the experiment—problem boxes (A–C).

Procedure

The testing in case of all three breeds was carried out during breed meetings at an outdoor location. The dogs had an opportunity to familiarize with the location prior to testing. The testing site was separated by at least 30 m from all other activity. The dog was facing the problem box, held loosely on a leash by the Owner, who was standing behind the dog slightly shifted to one side. The experimenter was initially standing in front of the dog, on the opposite side of the problem box. All trials started with the Experimenter drawing the dog’s attention to the reward (a small piece of Viener sausage), then opening the box and placing the reward inside, while being observed by the dog, still held on a leash by the Owner, approx. 1 m from the box. After the Experimenter visibly placed the reward into the box and showed an empty hand, she moved behind the dog and stood beside the Owner. When this position was taken up (both humans were stituated behind the dog’s line of site), the dog was allowed to attempt to open the box. Visual contact between dogs and humans was only restricted by their position. Dogs were allowed to try to open the problem boxes for 2 min. The boxes were presented once each, in a random order, with a 3 min. the interval between trials, three trials in total. All sessions were video recorded.

Data analysis

Videos of testing trials were coded for success and latencies to open the problem box, as well as for behaviour variables in orientation of the face, nose use and paw use. The complete list of coded variables may be found in Table 1.

We analysed the data using R statistical software (version 4.1.1)51 in Rstudio52.

The time measures of Orienting at the Owner, Orienting at the Experimenter, and Orienting at the box, were transformed into percentage of the total time because the length of the trials depended on the Opening latency. The time measures of Nose usage and Paw usage were transformed to the percentage of the manipulation time. All subjects manipulated the box at least once. Due to the mutually exclusive connection found between Nose usage and Paw usage, the large proportion of Nose usage (89.52 ± 24.47% of manipulation time) and the rarity of Paw usage (10.48 ± 24.47% of manipulation time), this data was transformed to Manipulation type binary score (0: only nose usage, 1: paw usage occurs) later. As the orientations (owner, experimenter, box) were closely connected, we ran a principal component analysis to summarise the behaviour variables into summary indices (“principal” functions of “psych” package53), after using parallel analysis to determine the number of components to extract (“fa. parallel” function of “psych” package53). All the behaviour variables were loaded into one component: the social behaviours (orienting toward the owner/experimenter) positively, and the non-social behaviours (orienting toward the box) negatively (Table 2). Thus, the component represented a social strategy over a problem-oriented strategy. Therefore, we named it ‘social strategy score’ (similarly to54). After calculating the social strategy score, we checked the internal consistency of the factor with Cronbach’s alpha (“alpha” function of “psych” package53).

Binomial Generalised Linear Mixed Model with logit link (“glmer” function of “lme4” package55) was used to check the possible associations between the opening success and dogs’ (1) breed, (2) box type and (3) sex as fixed factors, and (4) age as a covariate, and (5) manipulation type as binary score, with subject ID as a random factor.

Survival analysis was suggested for latency outcomes in behavioural experiments56; thus we used the Mixed Effects Cox Regression Model (“coxme” function of “coxme” package57) to analyse the effect of (1) breed, (2) box type and (3) sex as fixed factors, and (4) age as covariate, and (5) manipulation type as a binary score on the opening latency, with subject ID as a random factor.

Due to the distribution of the orientation factor score data (social strategy score), Zero-Inflated Beta Regression Mixed Model (“glmmTMB” function of “glmmTMB” package58) was used to examine its possible associations with (1) breed, (2) box type and (3) sex as fixed factors, and (4) age as a covariate, with subject ID as a random factor.

A Binomial Generalised Linear Mixed Model with logit link (“glmer” function of “lme4” package55) was used to check the possible associations between manipulation type and (1) breed, (2) box type and (3) sex as fixed factors, and (4) age as a covariate, with subject ID as a random factor.

For all the models, bottom-up model selection was used (“anova” function of “stats” package51), where the inclusion criteria were a significant likelihood ratio test for each tested variable. The most parsimonious models are presented below. A Tukey post-hoc test was used for comparisons between the three breed groups and the three box types (“emmeans” function of “emmeans” package59).

Ethical statement

The reported research project is in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines of Research in Hungary. The behaviour experiment was conducted with the permission of the National Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (number of ethical permission: PE/EA/128-2/2017). Owners volunteered with their dogs to participate in the study, received no monetary compensation and gave written consent. All owners signed an informed consent form. Dogs and owners could freely decide to leave the sessions at any time. Methods are also in agreement with ASAB guidelines.

Results

Success

We found a significant effect of breed (p < 0.001) and box type (p < 0.001) on the success, but sex, age or manipulation type effect and no interaction between breed and box type were found. English bulldogs and French bulldogs were less successful than mudis (EB: ß ± SE: − 2.61 ± 0.83; Z = − 3.16; OR = 0.07 [0.01–0.51]; p = 0.005; FB: ß ± SE: − 2.73 ± 0.83; Z = − 3.31; OR = 0.07 [0.01–0.45]; p = 0.003). Dogs were less successful with opening box A and B than box C (A: ß ± SE: − 2.32 ± 0.81; Z = − 2.86; OR = 0.10 [0.01–0.66]; p = 0.012; B: ß ± SE: − 3.17 ± 0.81; Z = − 3.90; OR = 0.04 [0.01–0.28]; p < 0.001).

Opening latencies

We found a significant effect of breed (p = 0.003) and box type (p < 0.001) on the opening latencies, but no sex, age or manipulation type effect and no interaction between breed and box type were found. English bulldogs and French bulldogs were slower than mudis (EB: ß ± SE: − 0.83 ± 0.30; Z = − 2.76; OR = 0.44 [0.22–0.88]; p = 0.016; FB: ß ± SE: − 0.97 ± 0.30; Z = − 3.26; OR = 0.38 [0.19–0.76]; p = 0.003; Fig. 2a). Dogs were slower with opening box A and B than box C (A: ß ± SE: − 1.08 ± 0.26; Z = − 4.22; OR = 0.34 [0.19–0.62]; p < 0.001; B: ß ± SE: − 1.59 ± 0.28; Z = − 5.76; OR = 0.20 [0.11–0.39]; p < 0.001; Fig. 2b).

Association between the opening latencies and the three breeds (a) and the three box types (b)—e.g. after 60 s elapsed, usually ~ 90% of mudis have already opened the box, while at the same time, only ~ 50% of English and French bulldogs had. Also, after 60 s elapsed, usually ~ 90% of dogs have already opened box C, while at the same time, only ~ 55% of dogs opened box A and ~ 45% of dogs opened box B.

Social strategy score

We found a significant effect of breed (p < 0.001) on the social strategy score, but no box type, sex or age effects were found. English bulldogs and French bulldogs had higher social strategy scores (look back longer at humans) than mudis (EB: ß ± SE: 1.43 ± 0.32; Z = 4.45; OR = 4.16 [1.95–8.91]; p < 0.001; FB: ß ± SE: 1.50 ± 0.32; Z = 4.70; OR = 4.49 [2.10–9.58]; p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Association between the social strategy score and the three breeds—English and French bulldogs had higher scores (oriented toward the humans more) than mudis.

Manipulation type

We found a significant effect of breed (p < 0.001) and box type (p < 0.001) on manipulation type, but no sex or age effect and no interaction between breed and box type were found. Mudis used their paws more than English bulldogs and French bulldogs (EB: ß ± SE: 1.72 ± 0.54; Z = 3.17; OR = 5.60 [1.56–20.04]; p = 0.004; FB: ß ± SE: 2.35 ± 0.59; Z = 3.95; OR = 10.46 [2.60–42.03]; p < 0.001; Fig. 4). Dogs used their paws more while opening box B than boxes A and C (A: ß ± SE: 1.72 ± 0.54; Z = 3.21; OR = 5.60 [1.59–19.71]; p = 0.004; C: ß ± SE: 2.40 ± 0.60; Z = 4.02; OR = 11.04 [2.72–44.82]; p < 0.001).

Association between the manipulation type and the three breeds—English and French bulldogs used their paws less than mudis.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify breed-specific behaviour differences between two brachy- and one mesocephalic breed in a problem-solving context to establish research data corresponding to owner reports of “positive behaviour traits for companionship”24. As prospective and present owners often justify their breed choice with this argument, we hypothesised that such differences exist and could be studied in an independent problem-solving context in the presence of owners. Our results seem to corroborate this hypothesis, as brachycephalic dogs orient significantly more at humans present than individuals of a mesocephalic breed when faced with a problem situation. As said before, looking back at the human in a problem situation may be mediated by other factors, such as breed type, life experience47,48,49 anxiety-related disorders46,50, as well as some anatomical characteristics which is an undoubted limitation of this study. For example, retinal ganglion cell distribution, and most importantly peak ganglion cell density in the area centralis have been found to be negatively correlated with skull length and positively correlated with cephalic index60. This has been suggested to result in better visual focus in the center of the visual field in case of brachycephalic breeds, possibly contributing to better visual communicative abilities in these breeds28,29,30. Moreover, due to brachycephalic dogs’ nostril stenosis61, nasal turbinate hypertrophy62, and significantly decreased olfactory brain63, being “short-nosed” may intuitively suggest poorer olfaction abilities, possibly resulting in lower motivation. However based on results comparing olfaction of brachycephalic and other breeds64,65, we may assume that—contrary to expectations—brachycephalic breeds do not differ from the general dog population in their olfaction abilities.

Still, this finding is particularly interesting as communication initiation, such as looking at the owner, was found to be in direct positive correlation with the emotional importance of the dog to the owner, as well as in direct positive correlation with the time spent in active engagement with the dog (Bognár et al. in prep). This suggests that this behaviour may indeed be partly responsible for owners’ desire for short-headed breeds.

Looking at the owner or the experimenter in a problem-solving situation, however, may be enhanced by various factors. On the one hand, small short-headed companion dogs could be genetically more inclined to act less independently (i.e. “baby-like” or “helpless”) to elicit human care. Such a trait would have a distinct advantage in an artificial selection context. On the other hand, it is possible that, mainly due to their physical appearance, owners treat brachycephalic dogs more like children; thus, they get more experience and positive feedback in communicative (“help-seeking”) situations, which experience then causes differences in behaviour. This hypothesis could be tested by contrasting the communicative behaviour of the owners of brachycephalic and mesocephalic dogs in a teaching or helping the situation with their relatively young dogs, possibly revealing more “parent-like” behaviour in owners of short-headed dogs. Also, testing puppies still at breeders in an identical paradigm could help disentangle genetic predispositions and the effect of life experience.

It is also plausible that brachycephalic dogs are less able to solve the problem due to physical constraints. We found evidence for this in limitations in paw use, but interestingly not in nose use. Based on the short nose, not very much protruding from the plane of the face, a natural hypothesis would be that nose use would be compromised in brachycephalic breeds. Our findings, however do not corroborate this hypothesis. Short-headed subjects used their paw less than subjects of the mesocephalic breed, but no difference was detected in case of nose use. A possible explanation of this could be that other anatomical issues, such as for example shorter limbs and neck, shape and weight of the head, rounder paws and body weight being centred over the front limbs66, making those more difficult to lift without losing balance, may outweigh the difficulty of manipulations with a short nose. Also, it is worth noting that manipulations by nose and mouth cannot be avoided, as those are absolutely necessary for feeding, while this is not necessarily the case for manipulations with the paws. Unfortunately, we are not able to untangle these factors based on present research. Most probably, it is safe to assume that there is an interaction of all the above-mentioned factors contributing to behaviour differences.

However, we have found stable evidence for enhanced orientation at humans in short-headed dogs when faced with a problem, which the human counterpart may well interpret as “helplessness”, help-seeking, and communication initiation—probably, together with baby-like looks, are a trigger for our basic nurturing instinct.

This may be the main reason why health and welfare-related issues if known, are mostly disregarded by owners acquiring small brachycephalic companion breeds. In their intriguing study on motives underlying pet ownership, Beverland et al.67 have found that some owners are even drawn to poor health status and related helplessness and vulnerability, as this makes them feel more needed.

While such motivation is marginal and far from being the standard, it seems that, like in many other instances, humans find it very difficult to cognitively override strong instinctive predispositions and still choose brachycephalic breeds, disregarding future health and welfare issues.

Data availability

Raw data is straight forward and not extensive and as such is provided as Supplementary material.

References

-

AKC. (2021). American Kennel Club. https://www.akc.org/

-

Packer, R. M. A., O’Neill, D. G., Fletcher, F. & Farnworth, M. J. Great expectations, inconvenient truths, and the paradoxes of the dog-owner relationship for owners of brachycephalic dogs. PLoS ONE 14, e0219918 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Packer, R. M. A. & O’Neill, D. G. Health and Welfare of Brachycephalic (Flat-faced) Companion Animals (CRC Press, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429263231.

Google Scholar

-

Teng, K. T., McGreevy, P. D., Toribio, J.-A.L.M.L. & Dhand, N. K. Trends in popularity of some morphological traits of purebred dogs in Australia. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 3, 2 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

UK Kennel Club. (2021). The Kennel Club. https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/

-

Roedler, F. S., Pohl, S. & Oechtering, G. U. How does severe brachycephaly affect dog’s lives? Results of a structured preoperative owner questionnaire. Vet. J. 198, 606–610 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Ekenstedt, K. J., Crosse, K. R. & Risselada, M. Canine brachycephaly: Anatomy, pathology, genetics and welfare. J. Comp. Pathol. 176, 109–115 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Fawcett, A. et al. Consequences and management of canine brachycephaly in veterinary practice: Perspectives from australian veterinarians and veterinary specialists. Animals 9, 3 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

O’Neill, D. G., Baral, L., Church, D. B., Brodbelt, D. C. & Packer, R. M. A. Demography and disorders of the French Bulldog population under primary veterinary care in the UK in 2013. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 5, 3 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Csatári, F. D. Kutyadivat 2023—mit választanak ma a magyarok, németek, japánok? https://hvg.hu/360/20230124_legnepszerubb_kutyafajtak_vilag_Magyarorszag_francia_bulldog_kutya_divat (2023).

-

Packer, R. M. A., Hendricks, A., Tivers, M. S. & Burn, C. C. Impact of facial conformation on canine health: Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. PLoS ONE 10, e0137496 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Nutbrown-Hughes, D. Brachycephalic ocular syndrome in dogs. Compan. Anim. 26, 1–9 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Conte, A. et al. Thoracic vertebral canal stenosis associated with vertebral arch anomalies in small brachycephalic screw-tail dog breeds. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 34, 191–199 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Lackmann, F., Forterre, F., Brunnberg, L. & Loderstedt, S. Epidemiological study of congenital malformations of the vertebral column in French bulldogs, English bulldogs and pugs. Vet. Rec. 2022, 190 (2022).

-

Barker, D. A., Tovey, E., Jeffery, A., Blackwell, E. & Tivers, M. S. Owner reported breathing scores, accelerometry and sleep disturbances in brachycephalic and control dogs: A pilot study. Vet. Rec. 189, 85 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Poncet, C. M. et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal tract lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs with upper respiratory syndrome. J. Small Anim. Pract. 46, 273–279 (2005).

Google Scholar

-

Reeve, E. J., Sutton, D., Friend, E. J. & Warren-Smith, C. M. R. Documenting the prevalence of hiatal hernia and oesophageal abnormalities in brachycephalic dogs using fluoroscopy. J. Small Anim. Pract. 58, 703–708 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Hall, E. J., Carter, A. J. & O’Neill, D. G. Incidence and risk factors for heat-related illness (heatstroke) in UK dogs under primary veterinary care in 2016. Sci. Rep. 10, 9128 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

O’Neill, D. G. et al. Canine dystocia in 50 UK first-opinion emergency-care veterinary practices: Prevalence and risk factors. Vet. Rec. 181, 88–88 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

O’Neill, D. G. et al. Epidemiological associations between brachycephaly and upper respiratory tract disorders in dogs attending veterinary practices in England. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2, 10 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Teng, K. T., Brodbelt, D. C., Pegram, C., Church, D. B. & O’Neill, D. G. Life tables of annual life expectancy and mortality for companion dogs in the United Kingdom. Sci. Rep. 12, 6415 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Packer, R. M. A., O’Neill, D. G., Fletcher, F. & Farnworth, M. J. Come for the looks, stay for the personality? A mixed methods investigation of reacquisition and owner recommendation of Bulldogs, French Bulldogs and Pugs. PLoS ONE 15, e0237276 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Sandøe, P. et al. Why do people buy dogs with potential welfare problems related to extreme conformation and inherited disease? A representative study of Danish owners of four small dog breeds. PLoS ONE 12, e0172091 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Packer, R., Murphy, D. & Farnworth, M. Purchasing popular purebreds: Investigating the influence of breed-type on the pre-purchase motivations and behaviour of dog owners. Anim. Welf. 26, 191–201 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Risk Factors for Dog Bites–An Epidemiological perspective. In (eds. Newman, J. et al.) (5M publishing, 2017).

-

Krainer, D. & Dupré, G. Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 52, 749–780 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Aromaa, M., Rajamäki, M. & Lilja-Maula, L. A follow-up study of exercise test results and severity of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome signs in brachycephalic dogs. Anim. Welf. 30, 441–448 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Gácsi, M., McGreevy, P., Kara, E. & Miklósi, Á. Effects of selection for cooperation and attention in dogs. Behav. Brain Funct. 5, 31 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Bognár, Z., Iotchev, I. B. & Kubinyi, E. Sex, skull length, breed, and age predict how dogs look at faces of humans and conspecifics. Anim. Cogn. 21, 447–456 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Bognár, Z., Szabó, D., Deés, A. & Kubinyi, E. Shorter headed dogs, visually cooperative breeds, younger and playful dogs form eye contact faster with an unfamiliar human. Sci. Rep. 11, 9293 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Stone, H. R., McGreevy, P. D., Starling, M. J. & Forkman, B. Associations between domestic-dog morphology and behaviour scores in the dog mentality assessment. PLoS ONE 11, e0149403 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

McGreevy, P. D. et al. Dog behavior co-varies with height, bodyweight and skull shape. PLoS ONE 8, e80529 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Paul, E. S. et al. That brachycephalic look: Infant-like facial appearance in short-muzzled dog breeds. Anim. Welf. 32, e5 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Borgi, M., Cogliati-Dezza, I., Brelsford, V., Meints, K. & Cirulli, F. Baby schema in human and animal faces induces cuteness perception and gaze allocation in children. Front. Psychol. 5, 85 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Jia, Y. C. et al. Adults’ responses to infant faces: Neutral infant facial expressions elicit the strongest baby schema effect. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 74, 853–871 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Lehmann, V., Huis in’t Veld, E. M. J. & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. The human and animal baby schema effect: Correlates of individual differences. Behav. Processes 94, 99–108 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Jack, S. & Carroll, G. A. The effect of baby schema in cats on length of stay in an Irish animal shelter. Animals 12, 1461 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Waller, B. M. et al. Paedomorphic facial expressions give dogs a selective advantage. PLoS ONE 8, e82686 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Thorn, P., Howell, T. J., Brown, C. & Bennett, P. C. The canine cuteness effect: Owner-perceived cuteness as a predictor of human-dog relationship quality. Anthrozoos 28, 569–585 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Topál, J., Kis, A. & Oláh, K. Dogs’ sensitivity to human ostensive cues. In The Social Dog 319–346 (Elsevier, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407818-5.00011-5.

-

Téglás, E., Gergely, A., Kupán, K., Miklósi, Á. & Topál, J. Dogs’ gaze following is tuned to human communicative signals. Curr. Biol. 22, 209–212 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Miklósi, Á. & Topál, J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 287–294 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Miklósi, Á. et al. A simple reason for a big difference. Curr. Biol. 13, 763–766 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Smith, B. P. & Litchfield, C. A. Looking back at ‘looking back’: Operationalising referential gaze for dingoes in an unsolvable task. Anim. Cogn. 16, 961–971 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Udell, M. A. R. When dogs look back: Inhibition of independent problem-solving behaviour in domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) compared with wolves (Canis lupus). Biol. Lett. 11, 9 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Marshall-Pescini, S., Passalacqua, C., Barnard, S., Valsecchi, P. & Prato-Previde, E. Agility and search and rescue training differently affects pet dogs’ behaviour in socio-cognitive tasks. Behav. Processes 81, 416–422 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

D’Aniello, B. & Scandurra, A. Ontogenetic effects on gazing behaviour: A case study of kennel dogs (Labrador Retrievers) in the impossible task paradigm. Anim. Cogn. 19, 565–570 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Scandurra, A., Prato-Previde, E., Valsecchi, P., Aria, M. & D’Aniello, B. Guide dogs as a model for investigating the effect of life experience and training on gazing behaviour. Anim. Cogn. 18, 937–944 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

D’Aniello, B., Scandurra, A., Prato-Previde, E. & Valsecchi, P. Gazing toward humans: A study on water rescue dogs using the impossible task paradigm. Behav. Processes 110, 68–73 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Passalacqua, C., Marshall-Pescini, S., Merola, I., Palestrini, C. & Previde, E. P. Different problem-solving strategies in dogs diagnosed with anxiety-related disorders and control dogs in an unsolvable task paradigm. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 147, 139–148 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria (2021).

-

RStudio Team, RStudio. “Integrated development environment for R.” RStudio, Editor (2018).

-

Revelle, William. “psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research.” Evanstone IL (2018).

-

Carballo, F., Cavalli, C. M., Gácsi, M., Miklósi, Á. & Kubinyi, E. Assistance and therapy dogs are better problem solvers than both trained and untrained family dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 74 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Jahn-Eimermacher, A., Lasarzik, I. & Raber, J. Statistical analysis of latency outcomes in behavioral experiments. Behav. Brain Res. 221, 271–275 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Therneau, Terry M. “coxme: mixed effects cox models. 2020.” Accessed September 22 (2020).

-

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Lenth, Russell V. “Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means [R Package Emmeans Version 1.6. 0].” Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) (2021).

-

McGreevy, P., Grassi, T. D. & Harman, A. M. A strong correlation exists between the distribution of retinal ganglion cells and nose length in the dog. Brain. Behav. Evol. 63, 13–22 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, N.-C. et al. Conformational risk factors of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS) in pugs, French bulldogs, and bulldogs. PLoS ONE 12, e0181928 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Buzek, A., Serwańska-Leja, K., Zaworska-Zakrzewska, A. & Kasprowicz-Potocka, M. The shape of the nasal cavity and adaptations to sniffing in the dog (Canis familiaris) compared to other domesticated mammals: A review article. Animals 12, 517 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Czeibert, K., Sommese, A., Petneházy, Ö., Csörgő, T. & Kubinyi, E. Digital endocasting in comparative canine brain morphology. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 741 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Hall, N. J., Glenn, K., Smith, D. W. & Wynne, C. D. L. Performance of Pugs, German Shepherds, and Greyhounds (Canis lupus familiaris) on an odor-discrimination task. J. Comp. Psychol. 129, 237–246 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Polgár, Z., Kinnunen, M., Újváry, D., Miklósi, Á. & Gácsi, M. A test of canine olfactory capacity: Comparing various dog breeds and wolves in a natural detection task. PLoS ONE 11, e0154087 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Mölsä, S. H. et al. Radiographic findings have an association with weight bearing and locomotion in English bulldogs. Acta Vet. Scand. 62, 19 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Beverland, M. B., Farrelly, F. & Lim, E. A. C. Exploring the dark side of pet ownership: Status- and control-based pet consumption. J. Bus. Res. 61, 490–496 (2008).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all dogs and their owners for participating in this research, as well as to Strázsa dog school and Szarvastanya at Portelek for providing the premises for our experiments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University. The study was supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences via a grant to the MTA-ELTE’ Lendület/Momentum’ Companion Animal Research Group (grant no. PH1404/21), the National Brain Programme 3.0 (NAP2022-I-3/2022), and the Hungarian Ethology Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.U., Á.M. and E.K. devised the project, the main conceptual ideas and proof outline. D.J.U. and M.M. carried out the behaviour experiments. D.J.U. and Zs. B. wrote the manuscript and contributed to the analysis of data with support from M.M., E. K. and Á.M. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ujfalussy, D.J., Bognár, Z., Molnár, M. et al. The difference between two brachycephalic and one mesocephalic dog breeds’ problem-solving performance suggests evidence for paedomorphism in behaviour.

Sci Rep 13, 14284 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41229-8

-

Received: 24 March 2023

-

Accepted: 23 August 2023

-

Published: 21 September 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41229-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.