Infection

Ukraine infections show rising threat from antibiotic resistance

Receive free Antibiotic resistance updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Antibiotic resistance news every morning.

In a US military hospital in Germany earlier this year, doctors made a worrying discovery when they examined a wounded Ukrainian soldier who had been defending his country against Russia’s invasion. His infection was resistant to almost every antibiotic available.

This episode, detailed in a paper published last month by the US Centers for Disease Control, is the latest evidence of the health effects of the war spreading far beyond Ukraine.

Since Russia first invaded parts of the country in 2014, the number of drug-resistant infections in western Europe has been rising — and a significant portion of those infected have been in Ukrainians, according to a flurry of scientific papers.

There are many ways in which war facilitates the spread of disease and makes it harder to take the usual precautions against antibiotic resistance. Heavy metals in bullets can be toxic, deep wounds expose the body to infection, hospital and hygiene infrastructure is damaged, tests to determine the correct antibiotic to use may not be available, the indiscriminate use of the drugs may be more likely, and population movement can spread disease.

In recent months, as evacuated troops and civilians have been admitted for treatment elsewhere in Europe, there has been a further rise in such infections.

Some of the infections appear to have been acquired during stays in Ukraine’s strained hospital systems; others have been transmitted more recently within the countries receiving hundreds of thousands of refugees.

But, despite this spread of antibiotic-resistant infections, the economic and political fallout from the war has distracted governments from mitigating the health threat.

Healthcare experts seeking to address this were disappointed at the UN general assembly last month, when three resolutions on tackling disease were passed but there was little sign of fresh funding or firm obligations to implement change.

Dame Sally Davies, the UK’s special envoy on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) — a term that encompasses antibiotic resistance — is pushing for a single, tougher and more focused resolution on AMR next year, including measures to track progress and hold nations accountable.

“We’ve got a massive work programme ahead of us,” she says. “We can only make it happen if the multilateral organisations work together [and] we have a framework agreed by countries.”

Around the world, the danger of AMR — given the limited repertoire of effective existing drugs — is growing significantly, with few new drugs in development.

Halting this growth is difficult, with measures limited to better prescribing, compliance, and infection control and trying to constrain environmental pollution and the excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics in animals.

Efforts are failing in even the most well-resourced healthcare systems. A patient in a prestigious New York hospital told the FT that antibiotics had been prescribed without sufficient tests to ensure they were appropriate for the infection — and then the in-house pharmacy refused to take back unused pills to ensure their safe disposal.

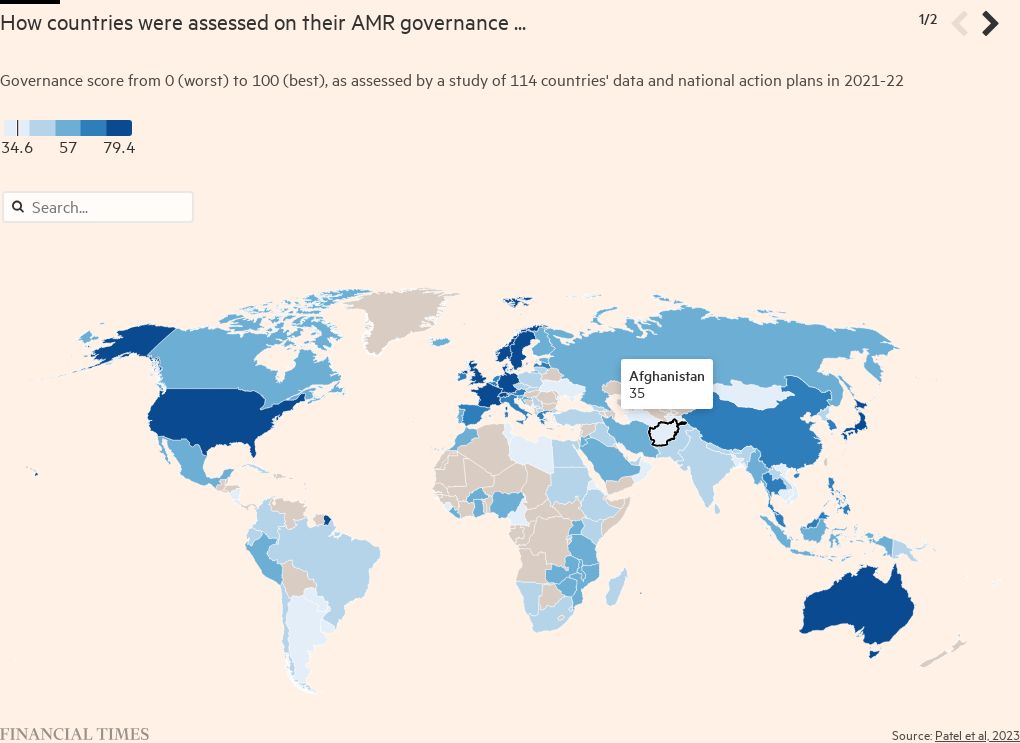

While most countries have produced national action plans on AMR, an evaluation published earlier this year by a team led by Jay Patel, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh, suggested widespread discrepancies in their quality, and a divergence between self-assessments and the views of external experts. “There is a tendency to overreport strengths and under-report weaknesses,” he says of the plans. “Nearly all of them are lacking in accountability.”

There are also substantial differences between the quality of national policies and estimates of deaths attributable to drug resistance in those countries. Zimbabwe and Japan are among those countries that received good evaluations but also have high death rates.

Muddying the water is the poor quality of data on AMR-linked deaths — estimated at 1.27mn annually worldwide. Countries that have invested in better surveillance and have more accurate data may be penalised, while infections — as the case of Ukrainians in Germany highlights — do not respect national borders.

Data from the Mapping Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use Partnership highlights that just 1.3 per cent of 500,000 laboratories in 14 African countries conduct bacteriological testing. Ramanan Laxminarayan, president of the One Health Trust, a think-tank, says that — in contrast to modelling projections — eastern and southern Africa has a greater AMR burden than west Africa.

Despite these difficulties, a growing number of initiatives suggest there could be some improvement in future. Artificial intelligence is being deployed for early stage research, and the pharmaceutical industry-backed AMR Action Fund has provided funding to support testing in patients of several promising experimental treatments.

Building on incentives in Sweden and Germany to encourage the uptake of new antibiotics, the UK has pioneered pilot schemes that reward the developers of innovative drugs with payments decoupled from usage — designed to limit excessive use. Similar measures are under discussion in Canada, the EU and the US.

Yet access to newer drugs in middle and lower income countries remains poor, threatening many patients’ lives and risking a further growth in resistance through inappropriate use of current drugs.

The Center for Global Development, a think-tank, argues for a new “grand bargain” that would balance responsibilities from industry, governments and multilateral organisations. While richer countries should pay for innovation and support poorer countries’ access and AMR plans, the poorer countries should ensure tight stewardship of new drugs.

“It’s not a silver bullet, but we have to fix the market for antimicrobials,” says Javier Guzman, the centre’s director of global health policy. “And we need accountability. AMR is a political as well as a technical issue.”