Infection

Protein Guard Mechanism May Be Used against Infectious Disease and Cancer

Researchers from the University of Birmingham report they have discovered the lock and key mechanism that controls the attack protein GPB1. The newly discovered mechanism prevents GPB1 from attacking cell membranes indiscriminately, creating a guard mechanism that is sensitive to disruption by the actions of pathogens inside the cells.

Their findings are published in Science in an article titled, “PIM1 controls GBP1 activity to limit self-damage and to guard against pathogen infection,” and led by Eva Frickel, PhD, senior Wellcome Trust fellow at the University of Birmingham.

The research reveals how GBP1 is controlled through a process called phosphorylation, a process in which a phosphate group is added to a protein by enzymes called protein kinases. The kinase targeting GBP1 is called PIM1 and can also become activated during inflammation. Phosphorylated GBP1 in turn is bound to a scaffold protein, which keeps uninfected bystander cells safe from uncontrolled GBP1 membrane attack and cell death.

The mechanism blocks GPB1 from attacking cell membranes indiscriminately, creating a guard mechanism that is sensitive to disruption by the actions of pathogens inside the cells. The new discovery was made by Daniel Fisch, a former PhD student in the Frickel lab working on the study.

“This discovery is significant for several reasons, said Frickel. “Firstly, guard mechanisms such as the one that controls GBP1 were known to exist in plant biology, but less so in mammals. Think of it as a lock and key system. GPB1 wants to go out and attack cellular membranes, but PIM1 is the key meaning GPB1 is locked safely away.”

“The second reason is that this discovery could have multiple therapeutic applications. Now we know how GBP1 is controlled, we can explore ways to switch this function on and off at will, using it to kill pathogens.”

Frickel and her team conducted this initial research on Toxoplasma gondii, a single-celled parasite that is common in cats. While Toxoplasma infections in Europe and Western countries are unlikely to cause serious illness, in South American countries it can cause reoccurring eye infections and blindness and is particularly dangerous for pregnant women.

The researchers found that Toxoplasma blocks inflammatory signaling within cells, preventing PIM1 from being produced, meaning that the “lock and key” system disappears, liberating GBP1 to attack the parasite. Switching PIM1 “off’ with an inhibitor or by manipulating the cell’s genome also resulted in GPB1 attacking Toxoplasma and removing the infected cells.

Frickel continued: “This mechanism could also work on other pathogens, such as Chlamydia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus all major disease-causing pathogens which are increasingly becoming more resistant to antibiotics. By controlling the guard mechanism, we could use the attack protein to eliminate the pathogens in the body. We have already begun looking at this opportunity to see if we are able to replicate what we saw in our Toxoplasma experiments. We are also incredibly excited about how this could be used to kill cancer cells.”

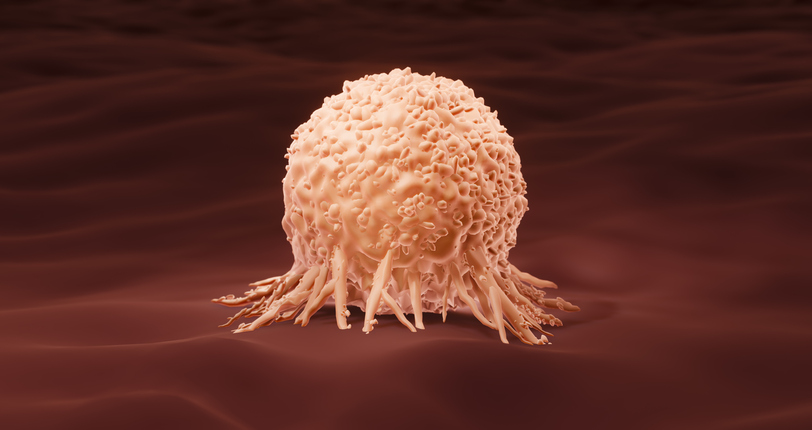

PIM1 is a key molecule in the survival of cancer cells, while GPB1 is activated by the inflammatory effect of cancer. The researchers think that by blocking the interaction between PIM1 and GPB1 they could specifically eliminate cancer cells.

Frickel said: “The implication for cancer treatment is huge. We think this guard mechanism is active in cancer cells, so the next step is to explore this and see if we can block the guard and selectively eliminate cancer cells. There is an inhibitor on the market which we used to disrupt PIM1 and GPB1 interaction. So, if this works, you could use this drug to unlock GPB1 and attack the cancer cells. There is still a very long way to go, but the discovery of the PIM1 guard mechanism could be a massive first step in finding new ways to treat cancer and increasingly antibiotic-resistant pathogens.”