Infection

What’s the state of Covid in the UK – and how is it being tracked?

As winter approaches we take a look at efforts to track the impact of Covid in the UK, and the insights they might provide.

What’s the current Covid picture?

While data from UK Health Security Agency (UKSA) suggested levels of Covid had risen in England over the past few months, with an increase in metrics including hospital admissions, the latest report indicates this appears to have stabilised.

However, what might happen in the coming weeks or months is unclear. Increased indoor mixing could increase the risk of respiratory infections spreading, including Covid, while questions remain about the potential impact of the new Covid variant BA.2.86.

“It seems like patterns of waning [immunity] and the evolution of [the] virus itself are still the main drivers for the sort of variation that we’re seeing,” said Prof Steven Riley, director general of data, analytics and surveillance at UKHSA. “[Covid] doesn’t seem to have dropped into any kind of resonance with seasonal factors.”

How are we keeping tabs on Covid?

Measures already in place include testing of certain individuals in hospital and other healthcare settings, swabbing of patients in particular GP surgeries, and reports of GP consultations where patients have turned up with respiratory symptoms. Covid outbreaks are also monitored, and deaths are tracked.

But many of the community surveys have been wound down, a situation that led some experts to warn the UK was almost “flying blind” this autumn.

While Riley said data currently collected offered a “pretty good picture”, he admitted it was not as comprehensive as before.

“It’s obviously not as good as it was during the height of the pandemic, but times have changed and we have to be somewhat proportionate to the changing risk,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean surveillance is static. UKHSA has begun boosting efforts in the run-up to winter – largely, said Riley, because it is when the NHS is under the most pressure.

Last month UKHSA announced a new phase of the Siren [Sars-CoV-2 immunity and reinfection evaluation] study. Dubbed Siren 2.0 it involves testing a cohort of healthcare workers for Covid, flu and RSV, whether or not they have symptoms, and will involved both PCR and antibody testing.

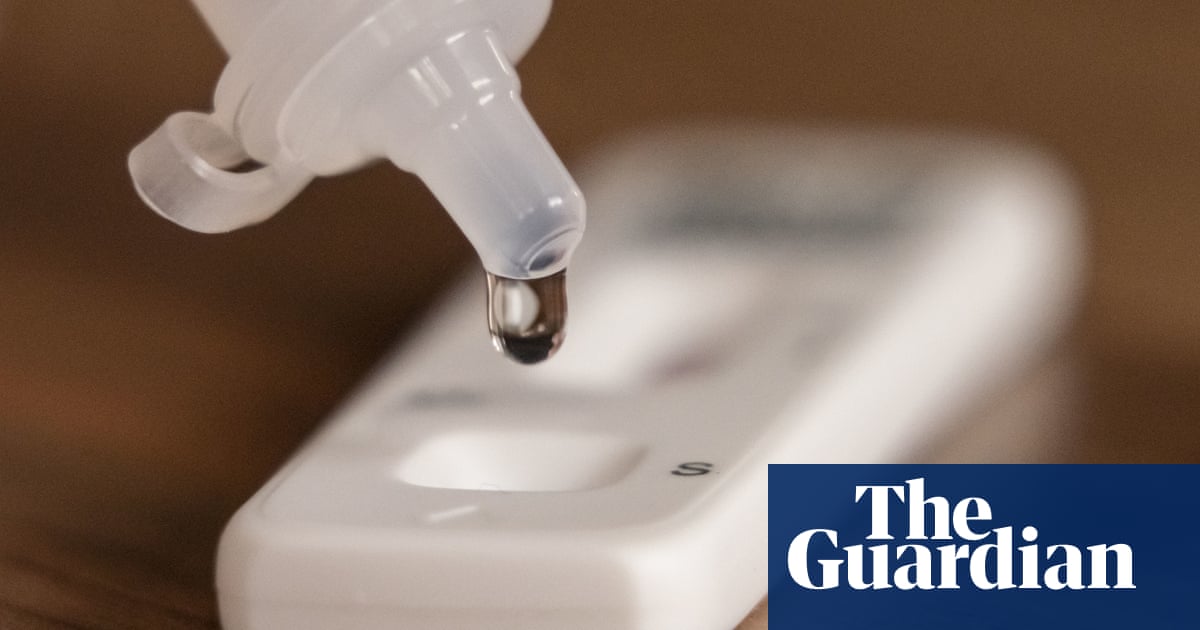

UKHSA and the Office for National Statistics has also announced a community-based winter Covid-19 infection study (WCIS), which will run from November 2023 to March 2024. This will see up to 200,000 participants in Scotland and England take a lateral flow device (LFD) test to pick up Covid infections, with 32,000 such tests being carried out each week.

What can these studies tell us?

The hope is that they will provide deeper insights into the spread and severity of Covid, as well as our defences against it.

“Siren 2.0 testing of healthcare workers, a cohort eligible for the booster vaccine, will help provide answers on vaccine efficacy against [BA.2.86], other circulating variants and infection-acquired immunity,” UKHSA said.

The WCIS meanwhile will offer a way to levels in the community – a picture that has been pretty opaque since the previous iteration of the study was paused in March. The new work will also offer a way to track certain changes in the virus.

“You can imagine not seeing an uptick in the community but seeing a significant increase in hospitalisations because [a variant] has become more severe,” said Riley.

Are there any problems?

There are certainly limitations. WCIS will be based on LFDs rather than the PCR tests that underpinned earlier work. That means it won’t directly provide information on particular Covid variants. It also means that, unlike last year’s study, it won’t offer data on levels of other respiratory infections like flu and RSV.

However Riley stressed other surveillance systems are in place for tracking RSV and flu, while the variation in hospital pressure created by flu over the past few years is not as large as that created by Covid.

Riley also said LFDs are faster and cheaper than PCR testing .

“The full cost of the study that uses an LFD is probably more proportionate to the risk,” he said.

What’s the plan if Covid goes big?

Good question. Riley said the new surveillance would offer a better situational awareness of Covid, and adding UKHSA also helps to generate options for ministers in response to threats.

While he declined to elucidate on what those options could be, data generated by UKHSA and partners will help the NHS plan for surges in demand.

But what it might mean for the public, and for advice around festive gatherings, remains to be seen.

“I have certainly no views on Christmas at this time,” said Riley.