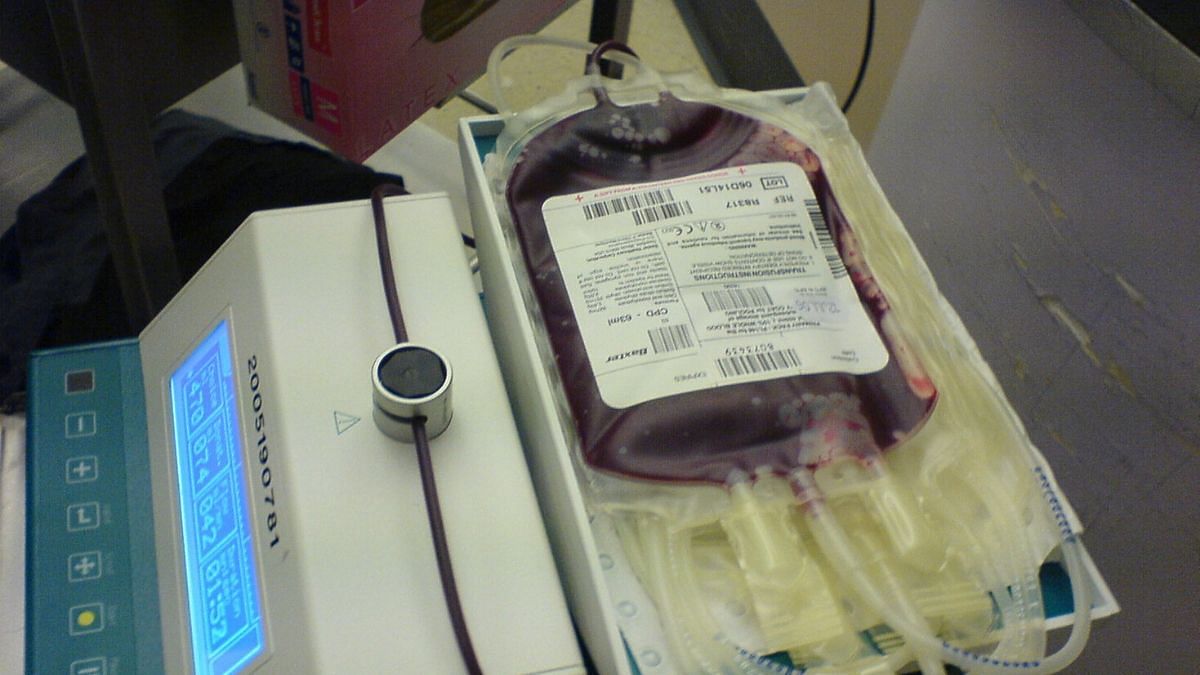

Blood

India’s blood banks are a danger zone. Patients’ trust in them is questionable

India’s pharmaceutical prowess has come under fire with some cough syrups reportedly having unacceptable levels of toxic compounds and being linked to deaths of at least 89 children in Gambia and Uzbekistan. While an investigation into the deaths goes on, a glaring example of continuing harm caused by healthcare-related policies lies unaddressed in one of the most unassuming places: Blood banks.

Blood banks are crucial to the management of any modern hospital system. Whether it be accident victims, surgical patients, childbirth, those suffering from anaemia or genetic conditions – for instance, beta-thalassemia – a huge swathe of society will, at some point, rely on the lifesaving services of blood banks. This relationship is premised on trust and safety, with the unspoken assumption that the blood provided will not harm the patient.

Unfortunately, it’s a questionable assumption because the prescribed standards for testing at Indian blood banks have, over time, fallen woefully short of the latest standards and technology.

Under The Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945 pursuant to The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, all blood samples must be tested for several serious infectious diseases: HIV-1 and HIV-2, Hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-Hepatitis C antibody (a sign the donor is currently or was previously infected with Hep C virus), malarial parasite, and VDRL (for syphilis).

Missing gold standard testing model

On face value, this appears in line with global practices for testing for transfusion-transmitted infections. However, the devil, as always, is in the details.

In Schedule F Part XII B Section J, the special reagents required for a functioning blood bank include ELISA and RPHA tests to test for the above-mentioned infectious diseases. Using the RPHA for disease detection is generally considered below par to the latest ELISA tests (currently fourth-generation, with fifth-generation tests being rolled out) in terms of its detection ability. For the ELISA testing method as well, there is remarkable heterogeneity, as the first test was invented in 1971 and many generations have evolved since then.

Unfortunately, the rules don’t seem to specify any minimum standard regarding the generation of ELISA tests required in a functional blood bank. In fact, huge variation has been reported in the type of tests used by Indian blood banks, ranging from ELISA (both outdated and current) to even rapid tests (akin to Covid-19 rapid tests), which definitely lack the sensitivity and specificity needed.

That’s not all: Many countries such as Australia, the UK, and Croatia have ensured all blood banks use the latest gold-standard NAT (Nucleic Acid Testing) to detect infections. NAT has become widely established because it is able to detect blood-borne infections much earlier than other methods. However, NAT testing is still not widely established in India with many preferring less-sensitive and cheaper testing systems. The last government report on NAT prevalence in 2016 stated that 4% of blood banks used NAT for HIV testing. Since then, official data seems hard to come by and estimates vary widely, ranging from 70% of blood banks quoted by The Times of India in 2019 to 10-12% of blood donations being stated in 2022. While the worst of these figures paint a dismal picture, even the highest estimates display a concerning gap with the adoption rates seen in developed countries.

In recent years, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Karnataka have floated tenders and created processes to mandatorily outsource NAT, for some patients, at blood banks. However, take-up remains patchy nationwide—higher at private hospitals and privileged ‘metro’ regions, but lower in small towns and rural areas. Consequently, many more Indians needing blood transfusions are put at risk of getting serious blood-borne diseases like HIV, Hep B and others—while being unaware of these risks.

These are not just theoretical quibbles about technology: In 2015, 8,938 people in India were infected with HIV due to blood transfusions in the previous five years. That is 8,938 lives overturned by the presence of an as-yet incurable disease—and many probably from poorer or more rural backgrounds where access to medications and ability to adhere to medication regimens may be lower. The numbers infected with Hepatitis C and Hepatitis B are likely to be even higher given their higher prevalence in India vis-à-vis HIV.

In 2018-19 too, 1,342 were infected with HIV from blood transfusions. Even in affluent states like Maharashtra, in 2023, it was reported that the entire Vidarbha region had no NAT at government-blood banks and that a number of children with Thalassemia major were victims of transfusion-transmitted infections.

These are staggering numbers and should spur us into action. Even one case of transfusion-transmitted infection that could have been prevented is one too many. Moreover, the negative impacts are faced more by the poor, especially the rural poor. This simply widens the pre-existing issue of health inequality in India.

Don’t let cost be a factor

To be clear, no test is perfect; even NAT cannot eliminate transfusion-transmitted infections—but it can bring down these numbers dramatically. As a visualisation, if a person was infected with HIV today and chose to donate blood daily, NAT would detect it (estimated) on the 6th day, fourth-generation ELISA on the 14th day, and third-generation ELISA on the 21st day. For Hepatitis C, the corresponding numbers would be the 4th, 10th, and 59th day (almost two months later), respectively.

While NAT is more expensive, I believe the costs can come down substantially with larger take-up, local production, and indigenisation.

India is a bona fide pharmaceutical superpower and produces quality pharmaceuticals at a scale and cost that is a fraction of much of the world. Companies like the Serum Institute of India, Cipla and many others have demonstrated the ability to innovate-at-scale and should be given the challenge of bringing down the costs for NAT tests to ease a national rollout.

The government is reportedly planning a major overhaul of The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940. It must act now to make NAT mandatory—or in the interim, fourth-generation ELISA—to ensure that nobody faces undue risks of getting bloodborne infections when established technologies exist to considerably reduce these risks.

The author is an undergraduate student at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)