Cancer and neoplasms

Impact of proton therapy on the DNA damage induction and repair in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Abstract

Proton therapy is of great interest to pediatric cancer patients because of its optimal depth dose distribution. In view of healthy tissue damage and the increased risk of secondary cancers, we investigated DNA damage induction and repair of radiosensitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) exposed to therapeutic proton and photon irradiation due to their role in radiation-induced leukemia. Human CD34+ HSPCs were exposed to 6 MV X-rays, mid- and distal spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) protons at doses ranging from 0.5 to 2 Gy. Persistent chromosomal damage was assessed with the micronucleus assay, while DNA damage induction and repair were analyzed with the γ-H2AX foci assay. No differences were found in induction and disappearance of γ-H2AX foci between 6 MV X-rays, mid- and distal SOBP protons at 1 Gy. A significantly higher number of micronuclei was found for distal SOBP protons compared to 6 MV X-rays and mid- SOBP protons at 0.5 and 1 Gy, while no significant differences in micronuclei were found at 2 Gy. In HSPCs, mid-SOBP protons are as damaging as conventional X-rays. Distal SOBP protons showed a higher number of micronuclei in HSPCs depending on the radiation dose, indicating possible changes of the in vivo biological response.

Introduction

Radiotherapy plays an important role, next to chemotherapy and surgery, in treating childhood cancers1,2,3. Normal tissue damage and secondary cancer risk from radiotherapy of primary cancers in adults are small compared to the benefits from radiotherapy. Unfortunately, children are at a greater risk than adults for developing cancer after being exposed to ionizing radiation, which is mainly due to the higher rate of tissue development and regeneration in children4,5. When individuals are exposed during childhood, the risk to develop radiation-induced soft tissue sarcoma, thyroid cancer, breast cancer or leukemia is significantly higher compared to adults4,5.

The high prevalence of radiation-induced leukemia in children is related to the high radiosensitivity of the hematopoietic tissue at young ages, particularly the bone marrow which harbors hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)6. HSPCs lie at the top of the hierarchic hematopoietic system where they have clonogenic potential and are capable of self-renewal and differentiation into all mature blood cells. HSPCs may be exposed in vivo to radiation during therapy either directly, when part of the bone marrow is irradiated, or indirectly, when HSPCs present in peripheral blood pass the radiation field. The specific characteristics of HSPCs make them a major target for radiation-induced normal tissue toxicity and possible malignant transformation as radiation-induced DNA damage may propagate genomic damage across the whole hematopoietic system7,8. In addition, the quiescent nature of HSPCs leads to an elevated vulnerability to mutagenesis due to the preference of error-prone non-homologous end-joining to repair double-stranded breaks (DSB)7,9.

In children, central nervous system (CNS) tumors represent 15–20% of all malignant neoplasms and are the most frequent solid tumors in the pediatric age as well as the leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality10. In these patients, approximately 20–30% of the active bone marrow is located in the cranium and cervical vertebrae11. Therefore, it is important to take red bone marrow into account during treatment of CNS tumors, as craniospinal irradiation is often standard of care in these patients12. This is further emphasized by the fact that bone marrow toxicity from radiation may limit subsequent local or systemic treatment regimens13. As the focus of most research today is to maintain or improve survival rates while attempting to reduce or eliminate long-term morbidities for each specific patient, radiotherapeutic treatments such as proton therapy are currently on the rise, in particular for treatment of childhood brain tumors11,14,15. Protons are ionizing charged particles and are different from high-energy X-rays, which are commonly used in radiotherapy11. While penetrating tissues, protons are slowed down and deposit most of their energy at the end of their range, which leads to a well-defined characteristic depth-dose distribution, called the Bragg peak. By modifying the energy of accelerated protons, the range of penetration can be adjusted. This allows for combination of multiple Bragg peaks into a spread-out-Bragg peak (SOBP), that encompasses the whole tumor, while reducing normal tissue doses16. This differs from conventional X-ray radiotherapy, where a relatively high entrance and exit dose are still present which may lead to toxicity problems for the healthy tissue surrounding the tumor and limits the ability to increase the tumor dose16,17.

Although proton therapy is now widely used to treat numerous cancers patients at over 98 clinically operational facilities, there are still hurdles to overcome in terms of physical dose delivery as well as unknowns about the radiobiology of protons16,18. The key metric by which proton and photon radiotherapy differ is the linear energy transfer (LET). LET is defined as the amount of energy per unit distance that is transferred to the surrounding medium by a particle along its trajectory (keV/µm) and is increasing along the depth of the SOBP19. The region of maximum LET is therefore located at the distal part of the SOBP20,21. A higher LET leads to a higher ionization density, leading to more complex DNA damage which is therefore more difficult to repair resulting in a higher yield of chromosomal aberrations. This has been seen in various in vitro studies22,23,24,25. To describe the biological effect of proton radiation, the proton relative biological effectiveness (RBE) is used. The proton RBE is the ratio of the absorbed doses that produce the same biological effect between a reference radiation (6 MV X-rays) and proton radiation26. In the clinic, a fixed RBE value of 1.1 for protons is typically used, which is based on experimental data and the fact that LET variations are not modeled in clinical treatment planning26,27,28. While there is evidence for a variable RBE along the proton beam depth, this remains a topic of active debate20,29. In particular, near the distal region of the Bragg peak several in vitro and in vivo studies showed a significantly higher RBE due to the higher LET, which can be critical as this SOBP portion is likely to be located in healthy tissue23,25,30,31,32. These recent findings question the accuracy of a fixed RBE value along the proton beam with respect to treatment safety and efficacy.

As exposure to radiation, particularly for pediatric cancer patients, is clearly correlated to a higher risk of leukemogenesis and as the proton biological effectiveness is still being questioned, it is crucial to investigate the radiation response of HSPCs in the light of the rapidly growing application of proton therapy. Multiple studies have suggested differences in DNA repair, cell survival and cell cycle perturbations between proton or photon therapy in different cells33,34. More specifically for human HSPCs, several studies on DNA damage response have been published with other radiation types but not with protons35,36,37. In this study, we investigated the differences in DNA damage induction and repair of human CD34+ cells, isolated out of umbilical cord blood (UCB), after exposure to high energy photon and proton irradiation at different SOBP positions by means of the γ-H2AX foci assay and the cytogenetic cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay (Supplementary file 1).

Results

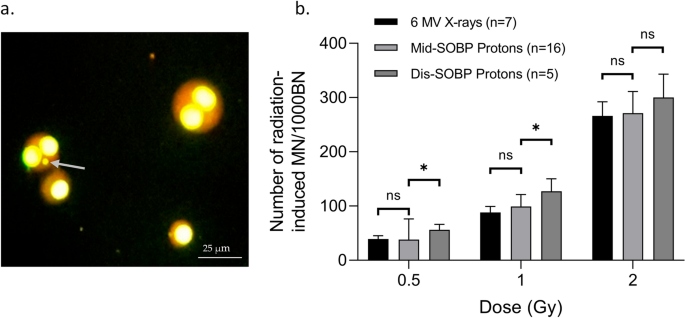

The MN, representing chromosomal damage, were counted. As shown in Fig. 1, the number of MN counted in 1000 BN cells showed no significant differences between 6 MV X-rays and mid-SOBP protons at each dose. CD34+ HSPCs were also exposed to distal SOBP protons at the PARTREC facility. When comparing their respective MN data to mid-SOBP protons and 6 MV X-rays, a higher number of MN/1000BN cells was found for the distal SOBP-exposed CD34+ HSPCs. This difference was significant for the 0.5 and 1 Gy exposure but not for the 2 Gy exposure. Hence, the proton biological enhancement ratios for distal SOBP protons are higher (up to 1.4) and the proton biological enhancement ratios for mid-SOBP are as expected (1.0–1.1) (Table 1).

(a) Image of mono and bi-nucleated (BN) CD34+ HPSCs at 400 × magnification. The grey arrow indicates a micronucleus. (b) The graph represents the number of radiation-induced micronuclei (MN) per dose (Gy) scored in 1000 binucleated (BN) CD34+ HSPCs, irradiated with 6 MV X-rays, mid- spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) protons or distal-SOBP protons, 70 h post-irradiation. The number of donors per condition is shown. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of the donors. Significance is indicated (*p < 0.05).

γ-H2AX foci were visualized by immunofluorescence, to detect the number of radiation-induced DSBs, whereby each focus theoretically represents one DSB. The analysis of foci, at different time points post-irradiation, gives an estimation of the induction and repair of DNA DSBs, whereby the amount of foci linearly increases with increasing dose and declines as a function of time post-irradiation38.

As represented in Fig. 2, the number of initial radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci at 30 min and residual radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci at 2 h post-exposure showed no significant differences between 6 MV X-ray, mid- or distal-SOBP protons. Also, residual radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci at 24 h post-exposure, indicating residual DNA DSBs, showed no significant differences between 6 MV X-ray, mid- or distal-SOBP protons (Fig. 2). This was also represented by a proton biological enhancement ratio of 1 for both mid- and distal SOBP protons, relative to the 6 MV X-ray exposures (Table 1). For each condition, significant differences were found between the radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci at 2 h and 24 h. Only for the 6 MV condition, a significant difference was found between 30 min and 2 h.

Image of the γ-H2AX foci present on a sham-irradiated (top) and an irradiated (bottom) CD34+ HSPCs: (a) 4′,6-diamidino-2-fenylindool (DAPI) staining (b) γ-H2AX foci on the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) channel c. Merged picture. Graph shows the mean radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci in CD34+ HSPCs at 30 min, 2 h and 24 h post-irradiation exposure to 6 MV X-rays, mid- spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) and distal SOBP protons. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean over the donors (n = 5). Significance is indicated (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the same number of initial double-stranded breaks (DSBs) were induced by exposure to 6 MV X-rays, mid- or distal SOBP protons, based on the number of γ-H2AX foci at 30 min. Also, at 2 h and 24 h post-irradiation no statistical differences were found between these conditions. Additionally, when comparing the number of radiation-induced DSBs between the different time points, all condition showed a significant difference between 30 min and 24 h, indicating DSB repair. Only the 6 MV X-ray condition showed a significant difference between 30 min and 2 h per condition. The significantly higher number of radiation-induced MN for distal SOBP protons compared to mid-SOBP protons and the higher biological enhancement ratio reflected a higher number of residual DNA damage at the distal end of the proton beam. The fact that no change in the number of γ-H2AX foci was observed at 30 min and 24 h, while a higher number of MN was observed after exposure to distal-SOBP compared to mid-SOBP protons, might be explained by a higher complexity of the DSBs induced by distal-SOBP protons. As mentioned before, this outcome has been seen in various in vitro studies and is linked to the increased LET in this region22,23,24,25.

However, RBE and their analogues do not only depend on LET but also on different biological properties such as the studied endpoint, the tissue type or cell line and the cell cycle stage39. Furthermore, RBE is also influenced by multiple physical properties such as the proton beam energy, dose and dose rate40. The obtained proton biological enhancement ratios can be used to further optimize RBE models, where RBE-weighted doses (DRBE) are used to incorporate differential RBEs in the irradiated volume. These RBE models are implemented in treatment plan optimization and evaluation as the use of generic RBEs may lead to inaccurate toxicity estimations41. Ultimately, for an optimal clinical use of proton therapy, approaches to limit treatment toxicity should be further developed while biological advantages of protons should be exploited42.

To further investigate the DNA damage response in HSPCs after irradiation, cell death analysis could be performed. Normal tissue injury during and following radiotherapy has been attributed to the loss of regenerative capacity, cell death and senescence in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment8. Besides apoptosis, novel highly controlled cell death pathways are emerging, which can be induced by radiotherapy43,44.

Our results indicate limited biological differences between proton and 6 MV X-ray irradiation for HSPCs. However, the extrapolation of our in vitro data to the clinical level is not that obvious, as the in vivo bone marrow is still a complex environment for HSPCs and intra- individual differences in the radiosensitivity of HSPCs are present, due to the heterogeneity within this cell population and inter-individual differences in HPSCs radiosensitivity have also been shown36,45. Also, UCB is neonatal peripheral blood which contains HSPCs that are more immature and possess a higher proliferative potential, and exist in higher concentrations than HSPCs found in bone marrow46. Nevertheless, our results provide a first insight into the fundamental DNA damage induction and repair mechanisms of HSPCs exposed to different beam qualities. The next step towards clinical translation would be to establish a murine model to further confirm the limited biological differences between both irradiation exposures in vivo. Finally, prospective clinical trials are required to assess the in human acute toxicity risks and long-term risk of developing hematological malignancies after proton exposure for pediatric patients with CNS tumors.

The fact that proton therapy reduces the integral dose to the patient compared to X-ray radiotherapy will result in a lower exposure of surrounding normal tissue and reduced risk to develop side effects. For hematological toxicity, this was recently illustrated by Vennarini et al.47 showing no acute hematological toxicity during cranio-spinal proton therapy for pediatric embryonal tumors. Next to this, Liu et al.48 showed that proton cranio-spinal irradiation significantly decreased hematologic toxicity compared with those receiving photon therapy. Also, Ruggi et al.12 showed in pediatric patients treated for medulloblastoma that hematological toxicity was limited, even among high-risk patients who underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation before proton therapy. For long-term risks, longer follow-up studies must be completed but current preliminary results on late effects and survival are certainly encouraging. Additionally, in the clinic other approaches to overcome the higher proton RBE in the distal part of SOBP include the use of different incident angles that selectively avoid proton beams stopping in or directly in front of the most radiosensitive healthy tissue39.

In conclusion, we showed similar DNA damage induction and repair between mid-SOBP protons and 6 MV X-rays in HSPCs while distal SOBP protons showed a higher number of MN in HSPCs compared to mid SOBP protons depending on the radiation dose. This research indicates possible changes of the in vivo biological response of proton therapy. Therefore, exposure to distal SOBP protons needs to be handled with extra caution during proton treatment planning. Further research is needed to fully understand the DNA damage response of HSPCs in more complex, in vivo animal models and more clinical studies are needed to collect data on acute and long-term outcomes after proton irradiation.

Methods

Collection and isolation of CD34+ cells

Informed consent for inclusion was received from all UCB donors, before participating in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol and informed consent was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ghent University (2017/1621). In total, 46 UCB samples were retrieved from the Red Cross Blood bank. First, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by density gradient centrifugation (density: 1.077 g/mL; Lymphoprep™, Axis-Shield, Dundee, UK). Then, HSPCs were purified by using CD34+ immunomagnetic beads (human CD34+ Microbead kit, Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. CD34+ purity and viability were checked as previously described by Engelbrecht et al.35. Flow cytometric analysis revealed an average CD34+ purity of 95.47% (SD: 3.62%) and a viability minimum was set at 95%. Isolated CD34+ HSPCs were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen after resuspension in 90% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and 24 h in a Mr. Frosty container, containing isopropanol, (Sigma-Aldrich) at − 80 °C.

Culturing and irradiation of CD34+ cells

Cells were thawed by washing them two times in complete Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (cIMDM: IMDM (Gibco), 0.5% pen/strep (Gibco) and 10% FCS; 37 °C) (1500 rpm, 10 min, 37 °C). For each radiation exposure, the CD34+ cell suspensions were irradiated in 1.0 mL cryogenic vials (Clearline CryoGen ®, Cona, Italy), positioned perpendicular to the beam axis.

Proton irradiation. Two proton facilities were used to irradiate CD34+ cells in mid-SOBP (iThemba LABS, Cape Town, South-Africa & PARTREC accelerator facility, University Medical center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands). To evaluate the difference between different proton SOBP positions, HSPCs were also irradiated at distal-SOBP at the PARTREC accelerator Facility.

Photon irradiation. 6 MV X-rays were used as the reference beam quality. For the cytokinesis-block micronucleus (CBMN) assay, a 6 MV LINAC at iThemba LABS was used. For the γ-H2AX foci assay, a 6 MV LINAC at Ghent University Hospital (Ghent, Belgium) was used.

Based on depth-dose curve measurements, correct positioning of cryovials, containing the CD34+ cell suspension, was assured by using specific in-house made sample holders and aligning them with lasers at both the proton and X-ray irradiation facilities. Physical parameters and additional information on both proton and photon beams can be found in Table 2.

The cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay

For this assay, the CD34+ cells were irradiated with 0.5, 1 or 2 Gy. A quantity of 200 000 CD34+ cells were cultured in 1 mL cIMDM and incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 1 h before irradiation in a cryogenic vial. After irradiation, cells of one vial were seeded out in two wells of a 48-well suspension plate (Greiner Cellstar®, Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were stimulated into division and the CD34+ micro-culture CBMN assay was performed as recently described by Engelbrecht et al.35. The nuclear division index (NDI) provides a measure of the cell’s proliferative status. For each culture, 500 viable cells (Ntotal) were scored to evaluate the number of mononucleate (N1), binucleate (N2), trinucleate (N3), and polynucleate (N4) cells. The formula used to calculate NDI: NDI = (N1 + 2N2 + 3N3 + 4N4)/Ntotal. For this study, all samples’ nuclear division indexes were within the range of 1.2–2.2 (data not shown). Micronuclei (MN), representing mainly acentric chromosome fragments that are not incorporated in the main nuclei after cell division, were manually scored in 1000 binucleated (BN) cells for each dose point (500 BN cells/duplicate culture) using a fluorescence microscope (200 × magnification, Leica). Details can be found in addendum A: ‘Cytokinesis-block micronucleus Assay’.

The γ-H2AX foci assay

For the γ-H2AX foci assay, 200 000 unstimulated CD34+ cells were incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 1 h in a cryogenic vial containing 1 mL cIMDM. After irradiation, the content of each cryogenic vial was divided over two cryogenic vials which were placed back in the incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Cells were incubated for 30 min, 2 h and 24 h post-irradiation, to detect γ-H2AX foci, representing DNA DSB induction (30 min) and repair (2 h, 24 h). After incubation the cells were placed on ice for 15 min, followed by cytospinning 250 μL cell suspension, representing 50 000 cells, on duplicate slides for both cultures. Then, immunostaining for the γ-H2AX protein was performed. Details on the immunostaining can be found in addendum B: ‘γ-H2AX foci assay’.

After leaving the immunostained slides overnight at 4 °C, slides were scored automatically with the MetaCyte software module of the Metafer 4 scanning system (MetaSystems, Altlussheim, Germany) using a 63x-oil objective with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter (z-stage = 10). At least 500 CD34+ cells were scored over duplicate slides from duplicate cultures. Afterwards, cell selection was manually checked for artefacts. For each beam quality, the average number of radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci was obtained by subtracting the mean number of γ-H2AX foci present in the sham-irradiated sample from the mean number of γ- H2AX foci in the irradiated samples of the same donor. At both 30 min and 2 h post-irradiation, the 30 min sham-irradiated control was used. At 24 h post-irradiation, the 24 h sham-irradiated control was used.

Biological enhancement ratio

Given the limited number of dose points in this study, a biological enhancement ratio was calculated instead of RBE. Biological enhancement ratio is the ratio of the radiation-induced biological effect (number of MN/1000BN cells or number of γ-H2AX foci) of proton irradiation relative to the reference irradiation (6 MV X-rays), for a specific radiation dose.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Graphpad Prism 9.4.1. software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Shapiro–Wilk tests assessed normality of data and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for the comparison of the number of radiation-induced MN/1000BN cells and the average number of radiation-induced γ-H2AX foci. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Abbreviations

- HSPCs:

-

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

- DSB:

-

Double-stranded break

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- SOBP:

-

Spread-out-Bragg peak

- RBE:

-

Relative biological effectiveness

- LET:

-

Linear energy transfer

- UCB:

-

Umbilical cord blood

- FCS:

-

Fetal calf serum

- cIMDM:

-

Complete Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium

- CBMN:

-

Cytokinesis-block micronucleus

- NDI:

-

Nuclear division index

- MN:

-

Micronuclei

- BN:

-

Binucleated

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-Diamidino-2-fenylindool

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

References

-

Gibbs, I. C., Tuamokumo, N. & Yock, T. I. Role of radiation therapy in pediatric cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 20, 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2006.01.015 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Jairam, V., Roberts, K. B. & Yu, J. B. Historical trends in the use of radiation therapy for pediatric cancers: 1973–2008. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 85, E151–E155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.10.007 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA-Cancer J. Clin. 63, 11–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21166 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Brenner, D. J. et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: Assessing what we really know. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13761–13766. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2235592100 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Hsu, W. L. et al. The incidence of leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma among atomic bomb survivors: 1950–2001. Radiat. Res. 179, 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1667/Rr2892.1 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Marcu, L. G. Photons—Radiobiological issues related to the risk of second malignancies. Phys. Med. 42, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2017.02.013 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Niedernhofer, L. J. DNA repair is crucial for maintaining hematopoietic stem cell function. DNA Repair 7, 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.012 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Shao, L., Luo, Y. & Zhou, D. Hematopoietic stem cell injury induced by ionizing radiation. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 20, 1447–1462. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5635 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Mohrin, M. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error-prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell Stem Cell 7, 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.014 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Smoll, N. R. & Drummond, K. J. The incidence of medulloblastomas and primitive neurectodermal tumours in adults and children. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 19, 1541–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.009 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Girdhani, S., Sachs, R. & Hlatky, L. Biological effects of proton radiation: What we know and don’t know. Radiat. Res. 179, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1667/Rr2839.1 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Ruggi, A. et al. Toxicity and clinical results after proton therapy for pediatric medulloblastoma: A multi-centric retrospective study. Cancers 14, 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112747 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Wang, Y., Probin, V. & Zhou, D. Cancer therapy-induced residual bone marrow injury-Mechanisms of induction and implication for therapy. Curr. Cancer Ther. Rev. 2, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.2174/157339406777934717 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Heath, J. A., Zacharoulis, S. & Kieran, M. W. Pediatric neuro-oncology: Current status and future directions. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 8, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01558.x (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Miralbell, R., Lomax, A., Cella, L. & Schneider, U. Potential reduction of the incidence of radiation-induced second cancers by using proton beams in the treatment of pediatric tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 54, 824–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02982-6 (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Vanderwaeren, L., Dok, R., Verstrepen, K. & Nuyts, S. Clinical progress in proton radiotherapy: Biological unknowns. Cancers 13, 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040604 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

De Ruysscher, D. et al. Author correction: Radiotherapy toxicity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0073-4 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Prasanna, P. G. et al. Normal tissue injury induced by photon and proton therapies: Gaps and opportunities. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 110, 1325–1340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.02.043 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Kavanagh, J. N., Redmond, K. M., Schettino, G. & Prise, K. M. DNA double strand break repair: A radiation perspective. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 18, 2458–2472. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.5151 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Ilicic, K., Combs, S. E. & Schmid, T. E. New insights in the relative radiobiological effectiveness of proton irradiation. Radiat. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-018-0954-9 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Paganetti, H. et al. Report of the AAPM TG-256 on the relative biological effectiveness of proton beams in radiation therapy. Med. Phys. 46, e53–e78. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.13390 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Hojo, H. et al. Difference in the relative biological effectiveness and DNA damage repair processes in response to proton beam therapy according to the positions of the spread out Bragg peak. Radiat. Oncol. (Lond. Engl.) 12, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-017-0849-1 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Horendeck, D. et al. High LET-like radiation tracks at the distal side of accelerated proton Bragg peak. Front. Oncol. 11, 690042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.690042 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Miszczyk, J. et al. Response of human lymphocytes to proton radiation of 60 MeV compared to 250 kV X-rays by the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay. Radiother. Oncol. 115, 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2015.03.003 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Singh, P. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of variable biological effectiveness of proton therapy in U-CH2 and MUG-Chor1 human chordoma cell death. Cancers 13, 6115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13236115 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Paganetti, H. Proton relative biological effectiveness—Uncertainties and opportunities. Int. J. Part. Ther. 5, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.14338/IJPT-18-00011.1 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

McMahon, S. J., Paganetti, H. & Prise, K. M. LET-weighted doses effectively reduce biological variability in proton radiotherapy planning. Phys. Med. Biol. 63, 225009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/aae8a5 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Paganetti, H. Range uncertainties in proton therapy and the role of Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, R99-117. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/57/11/R99 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Hojo, H. et al. Difference in the relative biological effectiveness and DNA damage repair processes in response to proton beam therapy according to the positions of the spread out Bragg peak. Radiat. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-017-0849-1 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Khachonkham, S. et al. RBE variation in prostate carcinoma cells in active scanning proton beams: In-vitro measurements in comparison with phenomenological models. Phys. Med. PM Int. J. Devoted Appl. Phys. Med. Biol. Off. J. Ital. Assoc. Biomed. Phys. (AIFB) 77, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.08.012 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Sorensen, B. S. et al. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) and distal edge effects of proton radiation on early damage in vivo. Acta Oncol. (Stockholm, Sweden) 56, 1387–1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1351621 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Saager, M., Peschke, P., Brons, S., Debus, J. & Karger, C. P. Determination of the proton RBE in the rat spinal cord: Is there an increase towards the end of the spread-out Bragg peak?. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 128, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2018.03.002 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Carter, R. J. et al. Complex DNA damage induced by high linear energy transfer alpha-particles and protons triggers a specific cellular DNA damage response. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 100, 776–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.11.012 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Szymonowicz, K. et al. Proton irradiation increases the necessity for homologous recombination repair along with the indispensability of non-homologous end joining. Cells 9, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040889 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Engelbrecht, M. et al. DNA damage response of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells to high-LET neutron irradiation. Sci. Rep. 11, 20854. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00229-2 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Heylmann, D., Rodel, F., Kindler, T. & Kaina, B. Radiation sensitivity of human and murine peripheral blood lymphocytes, stem and progenitor cells. BBA-Rev. Cancer 1846, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.009 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Kraft, D. et al. Transmission of clonal chromosomal abnormalities in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells surviving radiation exposure. Mutat. Res. Fund. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 777, 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2015.04.007 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Kinner, A., Wu, W. Q., Staudt, C. & Iliakis, G. gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5678–5694. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn550 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Sorensen, B. S. et al. Does the uncertainty in relative biological effectiveness affect patient treatment in proton therapy?. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Therap. Radiol. Oncol. 163, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2021.08.016 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Friedrich, T. Proton RBE dependence on dose in the setting of hypofractionation. Br. J. Radiol. 93, 20190291. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20190291 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Ramesh, P., Lyu, Q., Gu, W., Ruan, D. & Sheng, K. Reformulated McNamara RBE-weighted beam orientation optimization for intensity modulated proton therapy. Med. Phys. 49, 2136–2149. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15552 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Haas-Kogan, D. et al. National cancer institute workshop on proton therapy for children: Considerations regarding brainstem injury. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 101, 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.013 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Huang, Z. T. et al. Necrostatin-1 rescues mice from lethal irradiation. BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 1862, 850–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.01.014 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Matt, S. & Hofmann, T. G. The DNA damage-induced cell death response: A roadmap to kill cancer cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 73, 2829–2850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2130-4 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Takahashi, K., Monzen, S., Hayashi, N. & Kashiwakura, I. Correlations of cell surface antigens with individual differences in radiosensitivity in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Radiat. Res. 173, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1667/RR1839.1 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Kato, K., Omori, A. & Kashiwakura, I. Radiosensitivity of human haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. J. Radiol. Prot. Off. J. Soc. Radiol. Prot. 33, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1088/0952-4746/33/1/71 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Vennarini, S. et al. Acute hematological toxicity during cranio-spinal proton therapy in pediatric brain embryonal tumors. Cancers 14, 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14071653 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, K. X. et al. A multi-institutional comparative analysis of proton and photon therapy-induced hematologic toxicity in patients with medulloblastoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 109, 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.09.049 (2021).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Umbilical cord blood biobank of UZ Gent for providing all the UCB samples. We would like to thank L. Pieters, G. De Smet, J. Aernoudt, E. Bes for technical assistance. Furthermore, we acknowledge E. Duthoo, S. Vermeulen and E. Beyls for their help with MN scoring. We would like to thank the Physics Advisory Committee at NRF-iThemba LABS and PARTREC for beam time allocation. A special thanks to the Radiation Biophysics team in Cape Town and the PARTREC team at Groningen for their help during beam time. This research was funded by ‘ENSAR2’ & ‘PARTREC UMCG’, ‘Bijzonder onderzoeksfonds Ghent University’ (BOFSTA20170018)’ and ‘Fonds voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek‘ (FWO, G051918N) funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and A.B. conceptualization and methodology of the experiments; S.S., A.B., O.V. and M.E. performed the lab experiments. S.S., A.B., A.V. and B.V. wrote the manuscript, revised and prepared the final version. B.V., C.D., E.D.K., C.V., M.V.G. performed dosimetry and prepared the beam set-up. A.B. supervised and was responsible for funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sioen, S., Vanhove, O., Vanderstraeten, B. et al. Impact of proton therapy on the DNA damage induction and repair in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

Sci Rep 13, 16995 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42362-0

-

Received: 27 April 2023

-

Accepted: 08 September 2023

-

Published: 09 October 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42362-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.