Blood

Early-stage ovarian cancer: New blood test may boost detection

- Ovarian cancer was the third most common gynecological cancer globally in 2020.

- High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian cancer.

- As there are currently no reliable screening tests for ovarian cancer, almost all cases are diagnosed at the advanced stage, lowering a woman’s survival rate.

- Researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC have developed a new blood test for the detection of early-stage ovarian cancer.

- The test can reportedly distinguish between cancerous and benign pelvic masses with up to 91% accuracy.

In 2020, ovarian cancer was the third most common gynecological cancer in the world.

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian cancer, accounting for about 75% of all cases.

If detected at an early stage, the 10-year survival rate for high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is about 55%.

However, almost all cases of this type of ovarian cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage, which lowers the 10-year survival rate to 15%. That is because there is currently no reliable screening test available for ovarian cancer.

Now, researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) are trying to change that by developing a new blood test for the detection of early-stage ovarian cancer that can distinguish between cancerous and benign pelvic masses with up to 91% accuracy — a higher rate than that of other tests currently available.

This study recently appeared in the journal Clinical Cancer Research.

Ovarian cancer begins in the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, all of which are part of the female reproductive system.

Early symptoms of ovarian cancer — such as bloating, abdominal pain, and frequent urination — are very similar to the types of symptoms a woman has during her menstrual cycle, urinary tract infection, or irritable bowel syndrome.

For this reason, ovarian cancer is commonly misdiagnosed as a different condition until the symptoms worsen and do not go away.

Because the ovaries are located deep inside the abdominal cavity, it is hard for a physician to detect a tumor during a pelvic exam. Additionally, unlike other cancers, ovarian cancer normally does not spread to other parts of the body.

Currently, there is no screening test specifically for ovarian cancer. However, researchers are working on resolving this issue.

“If we can detect high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma in its earlier stages, we believe outcomes will be dramatically improved for women afflicted with this disease,” Dr. Bodour Salhia, interim chair of the Department of Translational Genomics, Keck School of Medicine of USC, leader of the Epigenetics Regulation in Cancer Research Program at USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, and corresponding author of this study explained to Medical News Today.

“We focused on high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma first because it is the most lethal and frequent type and we knew that other subtypes are likely [to] need different markers, something we confirmed in this study and is likely one of the reasons other attempts to develop ovarian cancer screening tools haven’t been successful,” she added. “We plan to include other subtypes in the test and are doing that now.”

In addition to difficulties in diagnosing ovarian cancer, once it is diagnosed doctors also have trouble determining whether the abnormal growth is cancerous or benign before surgery to remove it.

”Unlike many other cancers, biopsies are typically not an option,” Dr. Salhia said. “That makes it hard for doctors to choose the best course of treatment.“

”Knowing more about the mass before surgery could point to which type of surgeon and which method of surgery is best for the patient,” she pointed out.

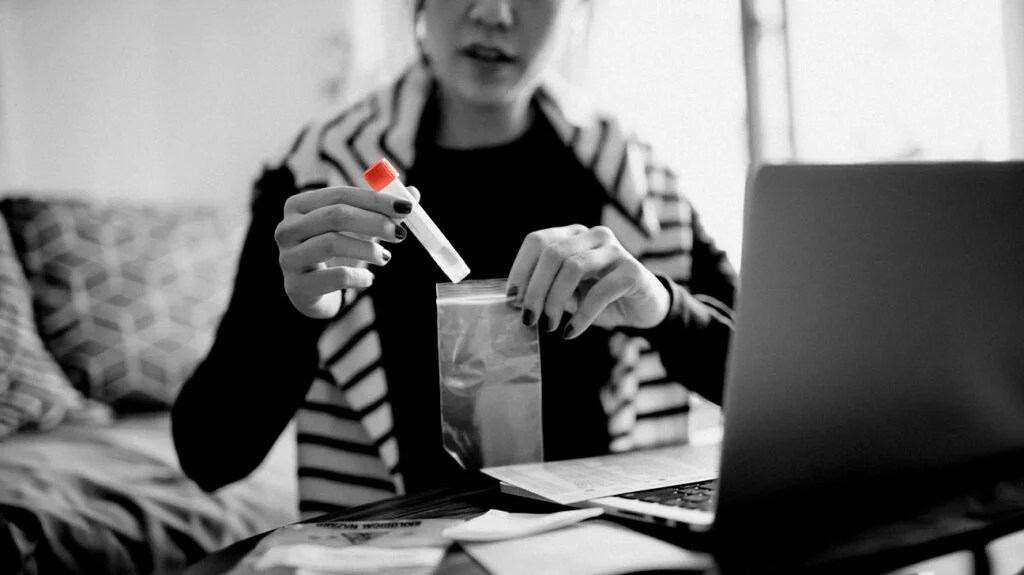

For this study, Dr. Salhia and her team developed a new blood test called the OvaPrint test to detect various types of early-stage cancers, including high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, and help physicians determine if a pelvic mass is cancerous or benign.

“The OvaPrint test uses a cell-free DNA methylation liquid biopsy approach, a promising new way to detect early-stage cancers of various types,” Dr. Salhia detailed.

“Our test works by detecting these small fragments of DNA shed by the tumor cells into the blood and are referred to as cell-free DNA because they are free from the cells they came from and they harbor alterations found in the tumor itself.”

– Dr. Bodour Salhia

“The test searches for this circulating DNA in the blood that has been methylated at certain nucleic acids,” she continued. “Methylation is a complex modification of DNA in cells that can alter the way genes are expressed in the body — and can also be used as a biological marker of disease.”

To test OvaPrint, researchers collected more than 370 tissue and blood samples from both people diagnosed with early-stage ovarian cancer and those with normal ovaries or benign tumors.

Upon analysis, researchers found the new blood test could distinguish between a cancerous and benign pelvic mass with up to 91% accuracy.

“It’s all about detecting ovarian cancers at early stages when it is more treatable and the outcomes are significantly better,” Dr. Salhia said. “There are still no effective screening tools for ovarian cancer for use in the general population. CA125 and ultrasound just don’t work well for ovarian cancer early detection, especially, because CA125 is non-specific and is elevated in many other conditions”

“We are launching a follow-up study to validate their results in hundreds of patients,” she added. “If the follow-up study results validate the efficacy of the test, we plan to release a commercially viable version of the test for clinical use within two years or less.”

After reviewing this study, Dr. John Diaz, chief of gynecologic oncology with Miami Cancer Institute, part of Baptist Health South Florida, and director of robotic surgery with Miami Cancer Institute, part of Baptist Health South Florida, not involved in the research, told MNT that gynecologic oncologists face several challenges in addressing women with adnexal masses.

“The surgical approach and intraoperative decision-making may change based on whether one suspects a benign or malignant ovarian mass,” he continued. “Having additional information preoperatively may help in determining the best surgical approach for these patients. This could result in improved surgical outcomes.”

Dr. Steve Vasilev, a board-certified integrative gynecologic oncologist and medical director of Integrative Gynecologic Oncology at Providence Saint John’s Health Center and professor at Saint John’s Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, CA, also not involved in the study, told MNT that since there is currently no effective screening tool for ovarian cancer, this is a step in the right direction in our current evolving molecular age.

“Techniques to assess cfDNA from malignant tumors and to identify and utilize other molecular biomarkers are much more sensitive compared to tumor markers currently used, like CA125,” he explained. “The reported sensitivity, specificity, as well as positive and negative predictive values are impressive, with an accuracy of over 90% as a triage tool.”

“However,“ he cautioned, “as provocative as this is, the data is very preliminary, as the authors acknowledge.”

Dr. Vasilev added that: “In order to prove the safety and efficacy of a screening tool, [it] can take many years of clinical trials or high-quality observational data with a very large population sample. Thus we are quite far from implementation as a general screening tool at this time.”