Infection

More adults under age 50 are getting shingles. Why?

Not long ago pop star Justin Bieber, 29, made headlines when he canceled an international tour after part of his face became paralyzed due to complications from shingles, an infection caused by the chickenpox virus and thought to affect only older adults. But the truth is, anyone can get shingles, and there’s some evidence that cases are increasing among adults under 50.

Between 1998 and 2019, the incidence of shingles increased across all ages but particularly among those in their 30s and 40s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The illness can trigger a painful, blistering rash usually on one side of the face or body, along with burning or tingling sensations, headaches, chills, an upset stomach, fatigue, and weakness.

A 2023 study from Duke University, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, found that cases of herpes zoster ophthalmicus—a form of shingles that affects the eye—increased at a slightly faster rate than the usual variety of shingles (herpes zoster) between January 2018 and December 2021. Notably, the study found that the incidence of both forms of the illness increased significantly among people in their 30s and 40s. An earlier study focused on a cohort in Minnesota between 1945 and 2007 revealed that shingles increased more than four-fold and the greatest relative bump was in adults younger than age 50.

What’s puzzling for experts is that even though there is a vaccine to prevent shingles in people 50 and older, “there has been a gradual, steady increase in the incidence of shingles over many, many years, and it has generally affected all age groups with the exception of young children,” says William Schaffner, an internist and professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. “The cause of the increase remains unknown.”

Why adults of any age can get shingles

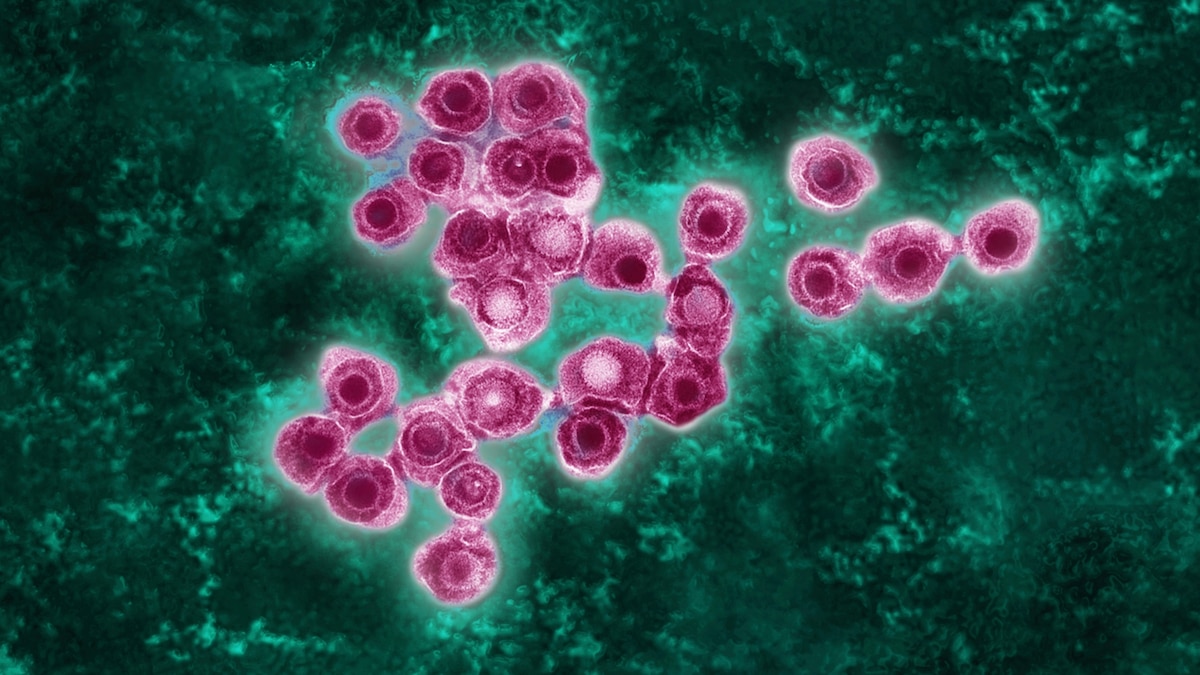

After someone has had chickenpox, the varicella zoster virus hides and remains dormant in certain nerves for years, sometimes decades. That’s why shingles can strike at any age after someone has had chickenpox.

“It’s so recognizable when the rash emerges—there’s nothing else that looks like this,” says Stuart Ray, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “Sometimes people have pain before the rash erupts and it’s hard to diagnose based on just the pain.”

Even after the telltale rash clears up, complications can occur. The most common one is a burning sensation in nerves and the skin, called postherpetic neuralgia, that can continue for months or even years. Other potential complications include bacterial skin infections, and eye damage and vision changes with herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

Shingles is usually treated with anti-viral medications, including acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. These drugs can shorten the length and severity of the illness, especially when they’re started within 72 hours of the rash’s appearance.

“Some people suffer through it without treatment, which is not a good idea because we have good treatments that shorten the duration and some evidence that early treatment may reduce the risk of complications,” Ray says.

Reasons for the uptick

Exactly why the overall incidence of shingles has been increasing, and why it’s been on the rise among adults under age 50, isn’t well understood. But there are hypotheses.

Before the development of the varicella vaccine, most people got chickenpox in childhood. This provided immunity when they were exposed to the virus as they got older. This meant that the immune system received regular reminders to keep up defenses against chickenpox and suppress the dormant varicella virus that was hiding in their own body.

But after the varicella vaccine became available in the United States in 1995, fewer children and adults were exposed to the highly contagious virus. Without this frequent exposure, which would help people maintain antibodies to the virus, the odds of varicella emerging from hibernation increased, explains Daniel M. Sullivan, staff physician in internal medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. “In the effort to make our children healthier, we have unfortunately made shingles more common in young adults.”

Another theory involves stress, which could contribute to reactivating the varicella virus in adults. In a study in a 2021 issue of the British Journal of Dermatology, researchers followed 77,310 people in Denmark, ages 40 and older, and found that people with high levels of perceived psychological stress in daily life had an increased risk of developing shingles over a four-year period.

Meanwhile, there has been some research about whether environmental factors—such as higher temperatures and higher humidity levels or seasonal changes—might play a role in shingles outbreaks. But some experts find this evidence thin. “We should be careful about interpreting single studies because these correlations are not very strongly supported by the data, and there are many potential confounders,” says Ray.

“There are oodles of people who get shingles and can’t figure out what triggered it,” Schaffner says. “It’s not something external. It’s something internal that causes this virus that was hibernating in their body to reactivate and come out as shingles.”

Preventive measures

Shingles itself isn’t contagious; but chickenpox is. If someone with a shingles rash—which is often brimming with fluid-filled blisters—comes into direct skin-to-skin contact with someone who has never had chickenpox or received the varicella vaccine, the exposed person can get chickenpox.

“People who never got chickenpox and never had the varicella vaccine should think about getting the vaccine,” says Ray. After all, chickenpox can be a more severe illness in adults and can lead to complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis (brain swelling), and sepsis (a bloodstream infection).

An added benefit of getting the chickenpox vaccine: “People who got the varicella vaccine have a lower risk for getting shingles than those who had chickenpox,” Ray adds.

Since the varicella vaccine became widely available, approximately 90 percent of children in the U.S. have been vaccinated against chickenpox, according to a study in a 2022 issue of the Journal of Infectious Diseases. If that trend continues, “there may come a time when chickenpox is eradicated and people can’t get shingles in the future,” Sullivan says. But we’re not there yet.

In the meantime, since 2017, there has been a highly effective way to prevent shingles in adults: the Shingrix vaccine.

“It is a spectacularly successful vaccine,” says Schaffner. “Yes, it takes two doses, and yes, it’s an ouch-y vaccine but that’s a small price to pay for protection from shingles.” The two-dose protocol is 98 percent effective in protecting against shingles during the first year after vaccination and 85 percent in the three years after that, according to the CDC.

The CDC recommends people 50 and older get two doses of the Shingrix vaccine, two to six months apart, regardless of whether they’ve had a shingles outbreak in the past or received the previous shingles vaccine (Zostavax) that is no longer used in the U.S.

In addition, the CDC recommends that people between the ages of 19 and 50 get the vaccines if they are immunocompromised. This could be because of a medical condition such as HIV, certain cancers, autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis, or an organ transplant. Or, it could be because of an immunosuppressive medication they’re taking (including biologics, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and long-term use of corticosteroid drugs).

People under 50 who fall into one of these categories should talk to their doctor about getting the shingles vaccine before age 50, Schaffner says. Not only are they at higher risk of developing shingles but they are also more likely to have complications—such as postherpetic neuralgia, skin infections, and eye complications—from shingles.

“A lot of people still don’t know about the shingles vaccine,” Schaffner says. “I’m usually not too keen on direct-to-consumer advertising but when it comes to this shingles vaccine, I think those ads on TV are right on the mark. They are good education.”