Infection

Viral reprogramming of cells increases risk of cancers in HIV patients, finds study

Viral infections are known to be a central cause of more than 10% of cancers worldwide. University of California researchers may have uncovered one of the key reasons why. Their findings were published today in PLOS Pathogens.

UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center researcher Yoshihiro Izumiya teamed up with Michiko Shimoda, who had previously worked in the Izumiya Lab at UC Davis. Currently she is a member of the Core Immunology Lab at UC San Francisco. Together, they led UC Davis researchers in the study of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The herpesvirus is linked to AIDS-related Castleman disease and multiple cancers such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphomas.

Immune response disrupters

KSHV is known for causing an inflammatory cytokine syndrome and is the leading cause of cancer death in patients with HIV, especially in sub-Saharan African patients. “Cytokine storms” can cause molecules secreted from immune cells to release large amounts of white blood cells, disrupting immune response.

“Viruses are infectious small particles, which can only grow in living organisms like humans,” Izumiya said. “In order to grow, viruses take over the function of host proteins and the viral infections often deregulate normal cell functions. KSHV-associated diseases are known to cause hyperinflammatory conditions or dysregulation of our body’s defense mechanism.”

Izumiya explained that immune cells help to protect against infections. Among immune cells, monocytes and macrophages are critical cells for defending against pathogens such as cancer cells. Macrophages are a small fraction of immune cells originating from monocytes. Once monocytes become macrophages, they acquire a longer life span and migrate to tissues such as the liver, lungs and skin to regulate inflammatory responses.

The role of vIL-6

The research showed that KSHV tends to infect one type of immune cells and the infection changes the fate of those cells. KSHV carries genetic information to make viral Interluken-6 (vIL-6), which is an inflammatory cytokine that stimulates inflammatory responses in tissue.

“We found that KSHV depends upon vIL-6 to expand infected monocytes, making more macrophages. However, these expanded macrophages have less ability to activate a type of immune cell called T-cells, a key player in the fight against pathogens and cancers,” Shimoda said. “Our results suggest two key points. First, KSHV cleverly uses its own IL-6 to increase the infected host cell, and, secondly, KSHV damages macrophage function and weakens our immune defense power.”

Essentially, the findings indicate that the reprogramming of immune cells by the KSHV infection increases inflammation in the body, leading to more infected cells in KSHV patients. The combination of biological effects is likely to make an infected individual vulnerable to secondary infections and cancer development.

Shared resource technology put to work

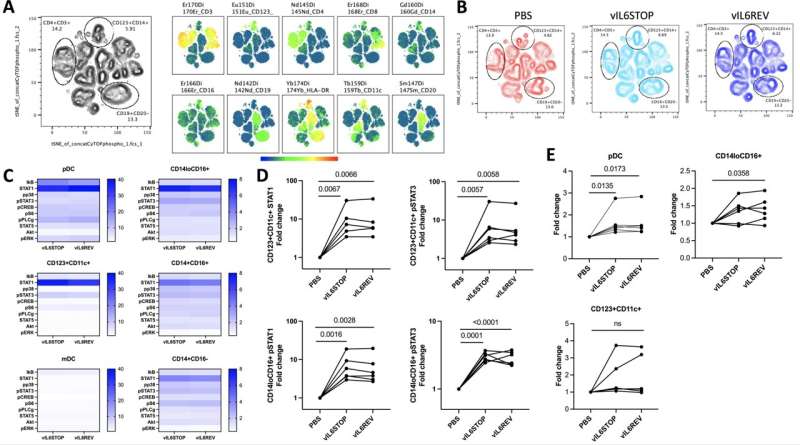

The team’s research combined state-of-the-art technologies such as single-cell sequencing, cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF) and artificially-produced KSHV infections to study the role of IL-6 in manipulating the human immune system. The instrumentation and expertise for these technologies were provided through UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Immune Modeling, Analysis and Diagnostic, Flow Cytometry, and Genomics Shared Resources.

“Our next goal is to help identify new therapies that target monocytes and macrophages to mitigate KSHV infection and its associated inflammatory diseases that can cause cancer,” Izumiya said.

“Our study also suggested that KSHV may take advantage of host inflammatory responses to maintain infections. Without continued inflammatory activations with own inflammatory cytokine expression, KSHV did not reactivate very well from infected cells. This study partly answered why inhibition of inflammatory cytokine expression with immunomodulatory drugs are effective in controlling KSHV-associated diseases.”

Other authors include Tomoki Inagaki, Ryan R. Davis, Alexander Merleev, Clifford G. Tepper and Emanual Maverakis, all affiliated with UC Davis.

More information:

Michiko Shimoda et al, Virally encoded interleukin-6 facilitates KSHV replication in monocytes and induction of dysfunctional macrophages, PLOS Pathogens (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011703

UC Davis

Citation:

Viral reprogramming of cells increases risk of cancers in HIV patients, finds study (2023, October 26)

retrieved 26 October 2023

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2023-10-viral-reprogramming-cells-cancers-hiv.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.