Infection

Malaria Is Spreading In The U.S. An Infectious Disease Doctor Explains This Troubling Trend

A patient developed malaria in Arkansas earlier in October, making now 10 cases this year that occurred in Florida, Texas, Maryland and Arkansas. None of those infected had traveled outside of the country to a risky area—meaning they caught it inside the U.S. This has not happened for 20 years.

Why Are The New Infections A Problem?

Malaria is treatable if it is diagnosed early, but things can go south fast and you can die without urgent treatment. We have become accustomed to not having malaria spread in the U.S., so even if you develop symptoms of infection, your doctor may not test for it, especially if you haven’t traveled to an “at risk” country. Also, there’s a specific type of mosquito that transmits malaria, and because it’s still found in parts of the U.S., if we let our guard down, it could exploit our vulnerabilities and cause a resurgence.

How Did The Recent Infections Happen?

Every year, around 2,000 individuals in the U.S. acquire malaria during travel to Asia, Africa or South/Central America. However, with the 10 new infections, someone inside the U.S. had likely contracted malaria abroad, then arrived in the U.S., was bitten by a mosquito, and that mosquito then bit someone else who had not traveled. Another possibility is that an infected mosquito hitched a ride on an airplane from a malarious country, escaped from the plane in the U.S. and bit someone. We call that “airport malaria.” As a preventive measure in some at-risk countries, the flight attendants spray an insecticide inside the plane before takeoff to reduce stowaway mosquitoes.

What Is Malaria?

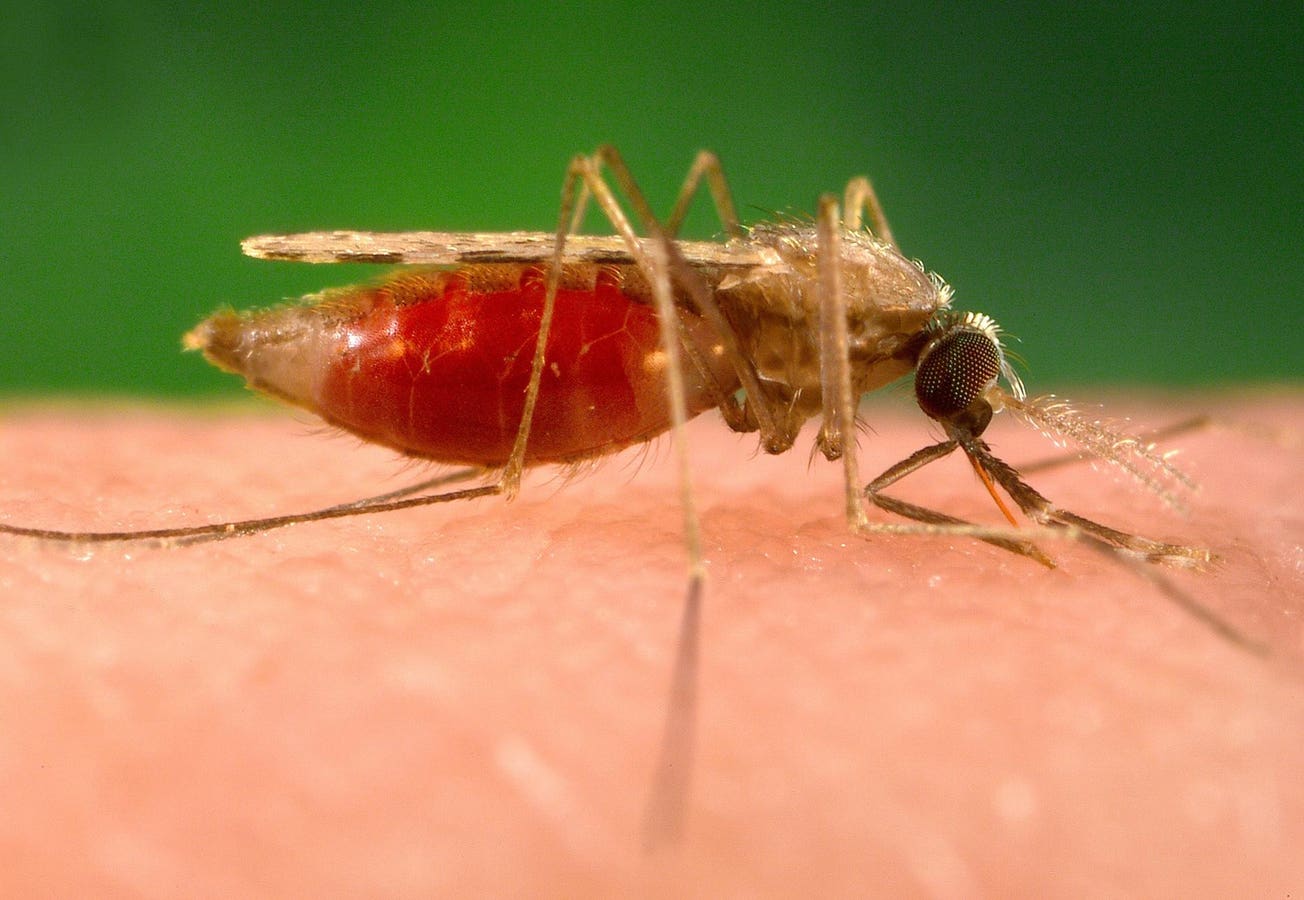

Malaria is caused by a parasite that one might conceive for a vampire flick, because after the mosquito bite, the organism that causes malaria travels first to the liver and later it lives and grows inside our red blood cells. Once the parasite reaches maturity, the cell explodes, releasing offspring into the bloodstream to infect more cells, thus repeating the reproduction cycle. When someone has malaria, they can’t spread it directly to others. It requires a specific type of mosquito (Anopheles) to transmit it. Unfortunately, Anopheles mosquitoes have been identified in 32 states in the U.S., so we have a potential problem. With the right conditions, we could have an outbreak.

Foul Air: The History Of Malaria

Malaria has devastated humans in tropical areas for centuries. The name malaria comes from “mala aria,” Italian for “foul” or “bad air,” but it’s not related to the kind of poor air quality we experienced in North America this year due to wildfires. Even though malaria doesn’t spread through the air, whoever named it recognized that it occurred in people exposed to swampy areas where the air smelled bad. It turns out, it was the mosquitoes breeding in the swamps that were spreading the disease, not the air.

Malaria used to spread commonly in southeastern parts of the U.S. However, with control measures, malaria risk dropped dramatically by 1949. In the 1950s, the World Health Organization started a campaign to eliminate malaria across the world by targeting mosquitoes with the pesticide DDT plus drainage of mosquito breeding sites. There was early progress, but the WHO ran into an unexpected problem—mosquitoes became resistant to DDT. The deadliest of the five malaria parasite species (Plasmodium falciparum) also developed resistance to the drugs used to treat and prevent it.

What Are The Symptoms of Malaria?

Malaria starts with shaking chills and a high fever, headache and fatigue (flu-like symptoms). After a day or so, the temperature drops, followed by profuse sweating. The person may feel relatively normal for a day or two until a new cycle of fevers begins. We diagnose it with a simple blood test or blood smear, but many other diseases can have similar symptoms as malaria early on, hence its nickname the “mime,” as noted in an American Journal of Medicine article that stated: “diagnosis was invariably, and often dangerously, delayed because physicians often made diagnoses of viral syndromes or used antibiotics.”

How Is Malaria Treated?

Malaria is readily treated if diagnosed early in infection. There are several oral and intravenous medications available. The type of recommended treatment depends on the type of malaria, where it was acquired and how ill the patient is.

Should You Worry?

Unlike populations living in parts of Africa, Asia and Central/South America, the general public in the United States, Canada and Europe has a very low risk of malaria unless they travel overseas. If you happen to live around the areas in Texas, Florida, Maryland and Arkansas, where the recent cases have occurred, it is reasonable to have a heightened awareness about malaria. If you develop compatible symptoms, get yourself evaluated, and don’t be shy about mentioning that you read about malaria in the news.

Before you travel overseas, be sure to consult your healthcare provider about malaria risk and prevention. In addition, use measures to avoid mosquito bites, such as insect repellant, cover bare skin and stay in screened-in areas or sleep under a bed net. One easy way to remember the riskiest times to avoid Anopheles mosquitoes is that, like vampires, they have an appetite for your blood primarily from dusk until dawn. Unfortunately, unlike with vampires, eating or hanging garlic won’t prevent you from getting bitten.