Infection

Reducing the rate of central line-associated bloodstream infections; a quality improvement project

Context

The hospital has a capacity of 280 beds with 46 adult critical care beds (ICU, HDU, CCU, and CTICU). The hospital laboratory is accredited by the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) and by the College of American Pathologists [23]. The microbiology laboratory utilizes the Becton Dickinson Bactec system for continuous blood culture monitoring and the bioMerieux Vitek2 for the identification of organisms.

A project team of 11 members was selected to implement the quality improvement project. Nearly all central lines in the hospital are used in the four critical care units that were chosen for the intervention. Interventions identified to reduce the rates of CLABSI were compliance with CVC insertion and maintenance bundles and active surveillance. Compliance rates for CVC insertion and maintenance bundles were initially assessed using a retrospective review of medical records pre-intervention. The interventions for this improvement project transitioned to real-time observation of practices to monitor compliance with bundle items using a standardized bundle checklist to accurately monitor practice, improve compliance and standardize audit process. Positive behavior of compliance to prescribed practice of adherence to CVC care bundles would be influenced through direct observations of practice.

Interventions

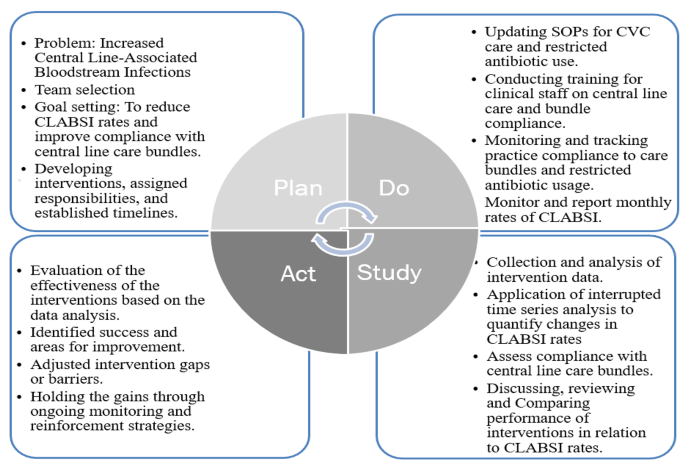

Clinical staff, doctors, and nurses, in the four critical units were engaged to brainstorm on the causes for increased central line-associated bloodstream infections. A Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model was used as a framework to guide the improvement project (Fig. 1).

During the “Plan” phase, the problem was identified as high rates in central line associated bloodstream infections and inaccurate compliance rates with central venous catheter insertion and maintenance bundles. The objective was to carry out a monthly surveillance and tracking of CLABSI rates and monitor practice compliance to CVC bundles through direct practice observations.

For the “Do” phase, the standard operating procedures for central line care bundles was reviewed, updated and shared with all staff, practice monitoring and tracking checklists for bundles compliance was standardized, staff were retrained on central line care bundles, and utilized the Centers for Disease and National Health and Safety Network (CDC/NSHN) criteria for CLABSI surveillance was reinforced to track cases.

The “study/ check” phase the project team analysed the compliance rates of CVC bundles and in relation to the CLABSI rates, compared bundle compliance data to previous performance to assess improvement, and convened a monthly multidisciplinary team meetings for an update of the team members roles and responsibilities and review and discuss project performance.

In the “Act” phase, we evaluated the effectiveness of bundle compliance in reducing CLABSI rates, identified the successes and areas for improvement of the improvement project, and made necessary adjustments to interventions while maintaining progress.

The National Health and Safety Network (NSHN) defines a central venous catheter (CVC) as an intravascular access device or catheter that terminates at or near the heart or in one of the major vessels, including the pulmonary artery, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, brachiocephalic veins, internal jugular veins, subclavian veins, external iliac veins, common iliac veins, or femoral veins [24]. Central line insertion bundle components that were actively implemented were compliance with hand hygiene before central line insertion, maximum barrier by staff while performing central line insertion, using a sterile drape on the insertion site, use of alcohol and chlorhexidine antiseptic for skin preparation, and allowing the site to air dry, and use of chlorhexidine-containing dressings. Compliance was calculated by dividing the total number of compliances to all five items of insertion bundles by the total number of observations for the CVC insertion bundle multiplied by 100. Maintenance bundle elements included hand hygiene before manipulating a central line, maintaining a clean and intact CVC, changing intravenous tubing every 72 h, ensuring stopcocks have dead-end sterile caps and are swabbed with a chlorohexidine antiseptic before access, and daily assessments of CVC necessity. Failure to adhere to all the bundle items was considered as “bundles not met” since it increased the risk of contamination of the central line that may result to CLABSI. Direct practice observation of central line insertions and maintenance of bundles was conducted by the unit clinical Nurse educator who were not directly involved in the procedures. Standardized bundle checklist was used during observations of practice compliance. Whenever a central venous catheter (CVC) insertion procedure was scheduled, a clinical nurse educator would directly observe the insertion to establish if all CVC bundle checklist items were met or not met. Central line insertions was based on clinical needs of patients, the number of samples to observed was determined by forecasted insertions from previous months number of insertions. For maintenance bundles, clinical nurse educator using RAND sampling for days and patients with Central lines used a CVC maintenance checklist to observe and assess for compliance to bundle items.

Surveillance for CLABSI was done both manually and electronically since our electronic health record at the time only supported laboratory and radiology. Patients’ notes was still using a manual system. Identifying patients who met the criteria for CLABSI involved extensive manual chart reviews to collect information of CVC insertions, utilization and removal. The infection prevention and control (IPC) team, infectious disease team, and critical care clinical teams collectively reviewed cases and determined if they met the National Health and Safety Network (NHSN) criteria for CLABSI, “lab-confirmed bloodstream infection in a patient who has had a central line for at least 48 hours on the date of the development of the bloodstream infection and without another known source of infection” and having the central line removed not more than 24 h prior to the date of a positive blood culture [12]. CLABSI rates (cases per 1000 catheter days) for each unit were then aggregated and reported monthly.

PDSA Implementation Framework

Statistical analysis

Interrupted time series (ITS) analysis was used to quantify changes in level and trend from pre- and during-intervention and assess if the estimated differences are statistically significant. Regression modeling was used to estimate coefficients for both the data segment preceding and succeeding an intervention [20]. The fitted regression equation model for the ITS is as follows; Y = β0 + β1(T)+β2(Xt)+β3(TXt)+εt Where Y represents the dependent variable.

T: Time elapsed since the beginning of the study.

Xt: Dummy variable representing the pre-and post-intervention period coded 0 and 1 respectively.

TXt: Dummy variable for the time lapsed after intervention.

β0: Baseline coefficient at the beginning of the study at T = 0.

β1: The change in the dependent variable when there is a unit change in time.

β2: The change in the dependent variable during the intervention period.

β3: The change in the dependent variable after the intervention period.

εt: Error term.