Infection

Poop transplants might protect vulnerable patients from superbug infections

Thousands of years ago, ancient Egyptians used moldy bread to heal infected cuts and wounds. They may not have realized it, but their bizarre medical practice relied on fungi to create chemicals that kill infection-causing bacteria. This, in other words, was a very rough draft of an antibiotic drug. These types of molds helped Alexander Fleming discover penicillin centuries later. And now, to fight off superbugs, scientists are increasingly turning to another unorthodox source of germ-killers: healthy poop.

Specifically, fecal microbiota transplants are safe and effective in stopping the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to a small study published today in Science Translational Medicine. If additional clinical trials prove to be successful, poop transplants could be a promising method in populations at risk of resistant infections, such as patients who get organ transplants.

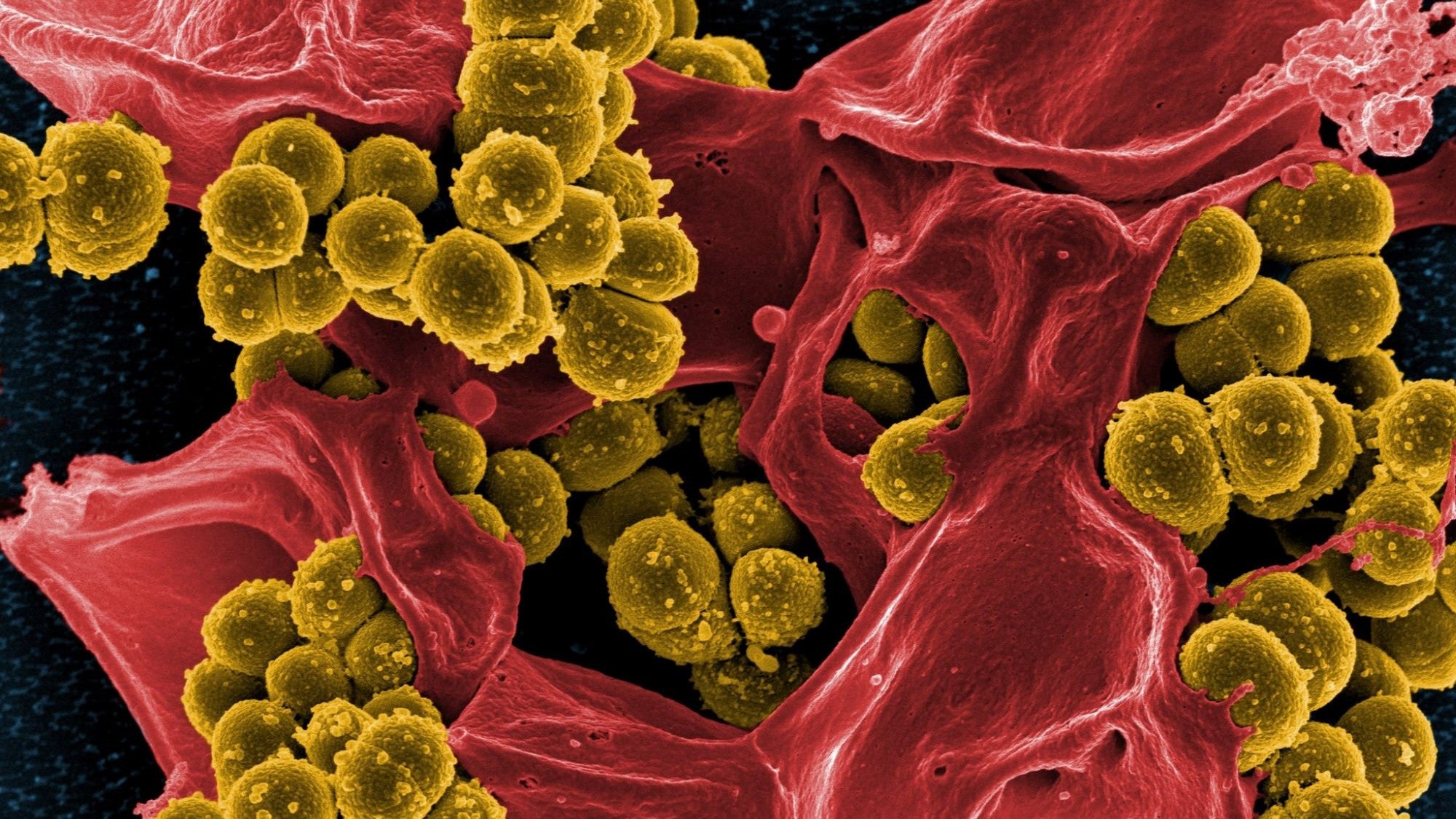

Antibiotics have saved millions from deadly infections, and human life expectancy jumped dramatically after their discovery. But their overuse has caused some bacterial strains to develop methods of protection against the medications. Antibiotic-resistant strains are a global problem that was responsible for 5 million deaths in 2019. On top of that is the concerning rise of superbugs, strains of bacteria with the highest resistance to multiple drugs.

[Related: FDA approves first fecal transplant pill]

Once a patient is infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, “there’s not really a way to get rid of colonization,” says Michael Woodworth, an assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and lead author of the new study. “Right now, there are no FDA approved therapies.” In the past, clinicians tried to get rid of superbugs with additional antibiotics, which can set up a “vicious cycle” in which medication promotes the growth of even stronger antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The idea to use poop transplants to defeat superbugs came after a growing body of evidence shows they can help treat tough C. difficile infections, a germ that patients can get in a hospital. In people who had received poop transplants, it looked as though they had fewer chances of catching the antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The new research was a Phase 1 clinical trial that enrolled 11 people awaiting kidney transplants. Organ recipients typically receive preventative antibiotics after their transplants, but this has not stopped an increasing amount of antibiotic-resistant UTI infections in this population.

In the study, people were randomly selected to receive a poop transplant immediately after getting a kidney, or a poop transplant later on if their stool samples showed positive signs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria after day 36. If people continued to be positive for the microbes, they had a second poop transplant. The authors used an enema to administer all the poop transplants, a route the study notes would have the lowest rate of side effects. To reduce the risk of passing harmful bacteria through the fecal transplants, screening tests checked for pathogens known to be resistant.

The research team detected significant results in the two groups, despite the small number of participants (COVID disrupted patient enrollment in the study). All treatments were safe for people who received one or two poop transplants. Additionally, eight out of nine people were negative for antibiotic-resistant bacteria after 36 days.

Genetic analysis of the stool samples showed that the poop transplants helped reduce the number of superbugs. This decolonization of bacteria, while it was not directly tested, may help in preventing recurrent antibiotic-resistant infections.

[Related: Finding the world’s super poopers could save a lot of butts]

“This provides the ground to start a large, randomized, controlled study to assess the effect of [fecal microbiota transplants] on decolonizing multi-drug-resistant organisms,” says Seifeldin Hakim, a gastroenterologist with Memorial Hermann in Houston who was not involved in the study. Theoretically, it would make sense that lowering the number of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut would decrease the chances of clinical infection or sepsis, Hakim says, but more evidence-based results are needed to support this.

Woodworth says poop transplants provide a mix of “good” bacteria to improve colonic health and strengthen the gut barrier. It’s also possible that another biological mechanism is at work. Woodworth hypothesizes that the poop transplants might have driven competition between antibiotic-resistant bacteria and non-resistant germs of the same species. This may have contributed to bacterial strains becoming more susceptible to antibiotics.

Because the trial was an early phase test, there are many more questions to answer, Woodworth says, such as figuring out the proper dose. His team is currently conducting two other clinical trials to research wider applications for fighting drug-resistant pathogens. They are currently planning a larger follow-up study, too, among people who received kidney transplants to better understand how competition between strains might reduce bacteria colonization.

There are still some kinks to work out with using fecal transplants, says Woodworth. However, he hopes this study can act as a jumping off point for inspiring other microbiome-related treatments to fight off antibiotic-resistant bacteria. To guide the next generation of therapies, poop may be our society’s moldy bread.