Infection

COVID-19 can interfere with your period in many ways. Here’s how.

Raven La Fae, a 32-year-old artist in Calgary, Canada, has always been able to predict their menstrual periods almost to the day; it arrived every 28 days and lasted for five. But after contracting COVID-19 in late 2020, that’s no longer the case.

La Fae’s bout with the disease lasted for two miserable weeks. A menstrual cycle landed expectedly during that time, but what was shocking to them was how long the bleeding continued—10 days.

“My period has been funky ever since,” La Fae laments, and after another round of COVID-19 it became even less predictable. While the days between cycles have mostly returned to baseline, the number of days of bleeding have not, lasting up to 10 days a month.

From the beginning of the pandemic, women worldwide noticed changes to their menstrual cycles. In some cases, this happened after contracting the virus; in others, after receiving a vaccine. With so many people recording their cycles in period-tracking apps, researchers have been able to document the phenomenon.

Initially, many physicians were taken off guard. La Fae’s healthcare provider, after determining hormone levels were normal, said she couldn’t explain it. People complained their doctors dismissed their hunch the virus might be linked to disrupted cycles.

“When COVID started we were worried about people dying, so other things were overlooked,” admits Hugh Taylor, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Yale Medicine. In retrospect, Taylor says, patients should have been alerted to this possibility. “We see irregular menstrual cycles with other acute infections, so it isn’t surprising it happens here.”

Poor messaging

Without research or reassurance from physicians, women were alarmed by the deviations in their periods, Taylor says, and for good reason: “We’ve been warning people for years that changes in a period might be a symptom of a hormonal imbalance, or even cancer.”

When girls and women noticed unexpected shifts in their cycle after receiving a COVID-19 shot, some second-guessed their decision to get a vaccine, says Candace Tingen, a program director at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which awarded $1.67 million to five research institutions to study the issue.

Tingen points out that her institute has long emphasized the importance of menstrual cycles to health. “We talk about it as a fifth vital sign,” she says (the other four being body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, and respiration).

Most concerning to younger women was whether these changes could reduce fertility, Taylor says.

It wasn’t until early 2022—two years into the pandemic—that a study of 2,000 American couples published in the American Journal of Epidemiology resolved the question. Women trying to conceive who’d had the virus saw no decrease in fertility. Similarly, the COVID shot had no impact on conception rates.

Both virus and vaccine may temporarily alter menstruation

Several NIH-funded studies have confirmed that COVID does alters cycle lengths in many women, albeit only briefly.

Thousands of reproductive-age women using a period tracking app reported that the time between their periods expanded by more than a day in the month following infection or vaccination, which for most returned to normal the following cycle, researchers reported in August.

Another study of 127 women of childbearing-age in Arizona who had contracted COVID found 16 percent reported some alteration; most common were irregular cycles or longer gaps between bleeds. These shifts were more likely in those whose infection involved more symptoms or was more severe (but not to the point of hospitalization).

Women in this study also had increases in the premenstrual syndrome symptoms of mood changes and fatigue.

“We think of the menstrual period as an acute event that occurs for a few days, but hormones are changing throughout the entire cycle,” explains Leslie Farland, an epidemiology professor at the University of Arizona and the study’s principal investigator.

A large study published in June focused on COVID vaccinations confirmed that here too the number of days between periods increases by about a day during the month of vaccination, but returns to normal after.

That aligns with a prior study tracking 4,000 U.S. women who used one period tracking app and found that, for the vast majority of women, cycles shifted slightly and temporarily; however, the length of bleeding didn’t change, says Alison Edelman, an obstetrician and gynecologist at Oregon Health and Science University and the study’s principal investigator. A second study by Edelman, of nearly 20,000 women in North America and Europe using the same app reported similar findings.

Still, ten percent of the women in Edelman’s study saw their period shift by more than a week after getting the shot. However, these women were also largely back to normal the following month.

None of these studies explain situations like La Fae’s, where menstrual cycles are changed significantly and persistently.

How does coronavirus change a period?

Exactly how the coronavirus or vaccine affects the menstrual cycle isn’t clear.

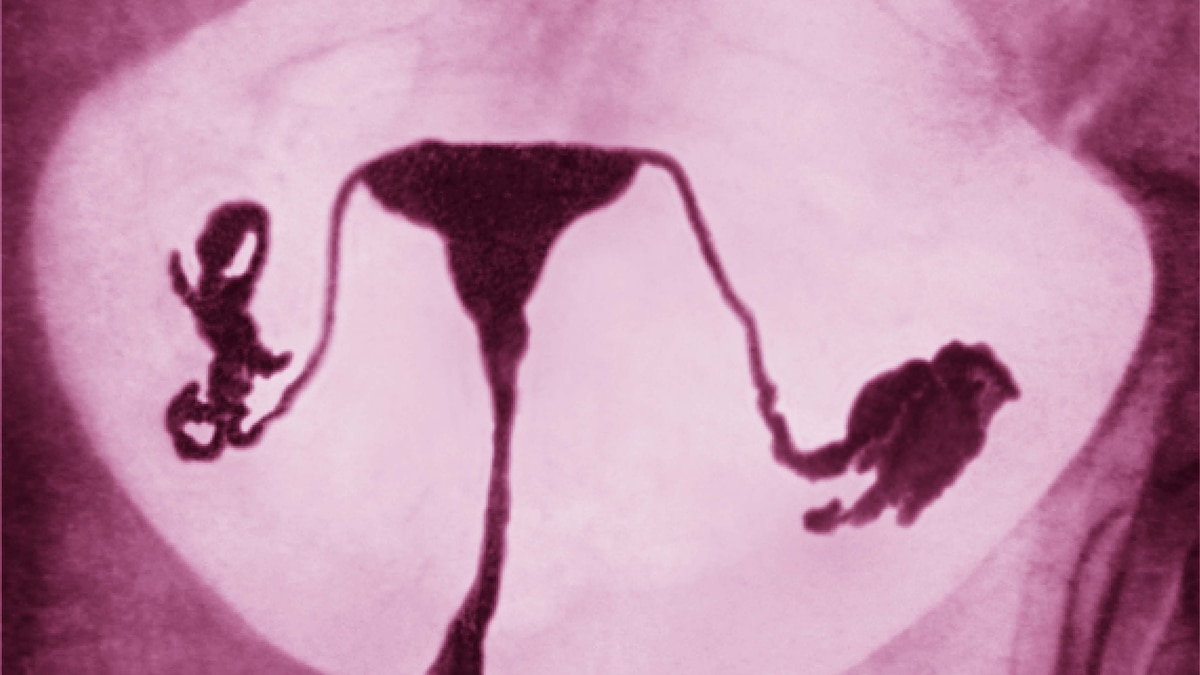

One hypothesis posits that COVID-19 may affect what’s known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. To begin each monthly cycle, the hypothalamus gland signals the pituitary gland to secrete two hormones that together release an egg from the ovaries.

It’s possible the coronavirus affects the hypothalamus directly, Taylor says, but the body may also proactively decrease the activity of these glands if the virus is detected. “This has evolutionary advantages, because you don’t want to get pregnant when you’re fighting off a physical stressor, which could be an illness or malnutrition or the like,” he explains.

Alternatively, the immune system engaged in fighting the virus could alter the normal inflammatory response of the uterine lining (endometrium) during the cycle. This may be why people who experienced a more intense bout of COVID—indicating a higher viral load and more immune activity—have higher rates of menstrual changes, as the University of Arizona study found.

That was the case for Annette Gillaspie, a 41-year-old registered nurse in Hillsboro, Oregon, who contracted COVID in 2020 and was extremely ill for more than two weeks. She has since experienced long COVID symptoms, including a fluctuating heart rate and fatigue so extreme a shower can send her to bed for days. Her periods are unusually long and heavy—gushing for almost two weeks some months—and even having a hormonal intrauterine device inserted didn’t reduce the bleeding as it normally does. At some point, she says, she’ll likely have to undergo a hysterectomy.

Vaccines trigger more minor shifts

Vaccines trigger the body’s immune system response, albeit a smaller one than the disease, so the same mechanisms could be involved in their temporary menstrual cycle disruptions, Tingen says.

Disseminating this reassuring information to women so they know to expect this possible side effect is an important public health task, Tingen says.

Anyone whose cycle remains significantly altered for several months, however, should check with their healthcare provider, Taylor says. “My suspicion is that people on the cusp of a medical condition—thyroid abnormalities, hormonal irregularities, bleeding from fibroids—might be pushed over the edge” by the coronavirus or COVID vaccine.

Edelman hopes this will be a teaching moment for her profession. “Menstrual health has been woefully understudied, not just in vaccine trials but in almost every area of research,” she says. “Yet half the population will, does, or has menstruated, and this routine biological function has meaning for the individual and for science.”