Infection

SVM awarded $3.7 million to help prevent coronavirus infections between animals and humans

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has awarded the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) $3.7 million in cooperative agreements to develop vaccines designed to prevent or limit the impact of future disease outbreaks that can spread between animals and humans.

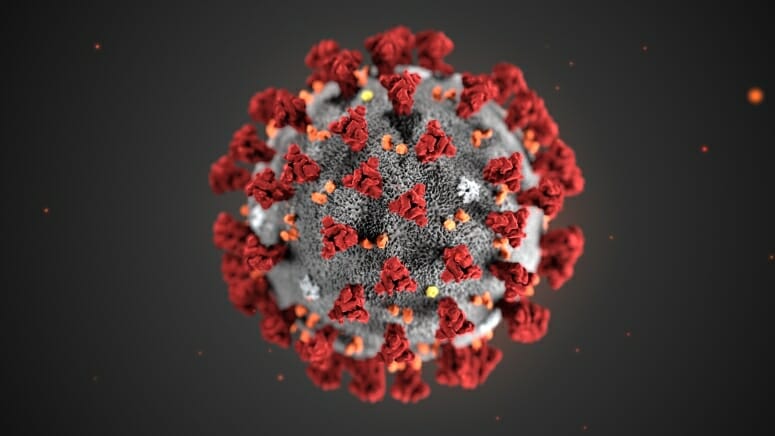

These cooperative agreements, which are part of a larger $56 million initiative by the USDA, will support two separate but related projects at SVM aimed at understanding how SARS-CoV-2 (the virus responsible for COVID-19) behaves in animals, how it moves between animals and people, and what can be done to interrupt the chain of transmission.

The ability of SARS-CoV-2 to mutate, adapt, and spread among domestic, wild and captive animals, and then jump from these animals to infect and cause severe disease in humans, is a major concern among public health officials.

The rapid development of vaccines and anti-viral medications have proven to be effective in preventing COVID-19-associated severe disease and hospitalizations, but the continuous emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 viral variants that evade vaccine- or infection-elicited antibodies can lead to breakthrough infections, and sometimes severe disease even in vaccinated people.

The following two projects funded by these cooperative agreements help prevent and/or limit the impact of future pandemics:

The first project, “Universal Mucosally Administered SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine for Animals,” is designed to identify effective interventions and other measures to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at the human-animal interface and help mitigate potential impacts on the food supply. The research team, co-led by Marulasiddappa Suresh and Jorge Osorio, both professors in the SVM Department of Pathobiological Sciences, will seek to develop pan-coronaviral vaccines that can be used to protect domestic and wild animals against several coronavirus infections, including COVID-19, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Their team will also explore formulating vaccines that could be administered to many animals via oral baits or nasal spray.

The end users of this research will include pets and their owners, production animals, susceptible wildlife species that serve as reservoirs for SARS-CoV-2 and other beta-coronaviruses, and human communities.

“In order to limit the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants in nature, it is critical that we develop effective tools that block the spread of the virus between humans and other animal species,” said Suresh. “Our goal is to create vaccines that can break that transmission cycle of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses at the animal-human interface, which, if we’re successful, would have significant implications for public health and ultimately play an important role in preventing future pandemics.”

This second project, titled “Multivalent Vaccines Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mustelids”

aims to expand knowledge of species susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and to better understand the potential roles or routes of transmission. One key feature of this project will be the development of mosaic vaccines that can protect against multiple variants as well as reduce both animal-to-animal and animal-to-human transmissions. Researchers will also evaluate the performance of novel vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. The project will be co-led by Adel Talaat, professor of microbiology, Peter Halfmann, research scientist, and Marulasiddappa Suresh, all in the SVM Department of Pathobiological Sciences.

The end-users of this research will include veterinarians who treat ferrets raised as pets and who manage farmed minks, herd owners of mink farms, vaccine companies and researchers of zoonotic diseases of wildlife animals that belong to the Mustelidae family, which include wild ferrets, mink, badgers and otters.

“By developing a protective COVID-19 vaccine for ferrets, a common pet in many households in the United States, we would not only be diminishing the chances of transmitting the virus to minks and other wildlife animals in our environment, but it would go a long way toward protecting human health as well,” said Talaat.

According to Dr. Michael Watson, APHIS acting administrator at the USDA, both of these research projects will help USDA/APHIS accomplish its goal of building an early warning system to potentially prevent or limit the next zoonotic disease outbreak.

“APHIS has long relied on collaboration with our state, Tribal, federal, and private partners to help protect our nation’s agricultural and natural resources,” Watson said. “We are excited about the opportunity these new partnerships give us to build critical One Health coordination and capacity while furthering the science on SARS-CoV-2. This important work will strengthen our foundation to protect humans and animals for years to come.”

“One Health” is a philosophical and scientific framework that recognizes humans, animals, and the world we live in are inextricably linked and that a collaborative effort of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally is necessary to attain optimal health for all species and the environments they share.

Founded in 1983, the UW School of Veterinary Medicine provides outstanding programs in veterinary medical education, research, clinical practice, and service that enhance the health and welfare of both animals and people and contribute to the economic and environmental well-being of the state of Wisconsin, the nation and the world.

-Gian Galassi