Congenital disorders

A mother was told to terminate her baby with Down syndrome. Now she works to uplift their voices.

Marsha Weigum was sitting in the office of her doctor in Carbondale when she was told that there was a 99% chance her son would be born with Down syndrome.

She’d received a call from her doctor earlier that day asking her to come in about her blood work.

“Down syndrome, the word is not strange to me,” Marsha said. “That’s the job I did. My favorite child of them all working with the organization was one with Down syndrome.”

Marsha was pregnant with her sixth child, though it was her first child with her husband Mark after immigrating to Colorado from Jamaica 16 years ago.

Her reaction to her doctor’s diagnosis was to ask, “What’s next for the prenatal care? Do we need to be doing something different?”

The Doctor’s response, however, encouraged a type of care that Marsha was determined not to pursue.

“She said … ‘you can terminate if you choose,’ Marsha said.

Her doctor continued to list the ways in which raising her unborn baby would be difficult: he would be a slow learner, dependent on family, among other concerns.

“I listened to her, but the minute she said termination, I didn’t think I wanted to hear much more,” she said. “These children are awesome, they’re innocent children, and now here I am having my own.”

Marsha returned her initial question: what’s next?

They discussed some of the risks, such as the chance that some babies born with Down syndrome could have heart defects and therefore need open-heart surgery.

With this perceived diagnosis on her hands, Marsha realized she wasn’t mad about her son being diagnosed with Down syndrome — she was mad about having to navigate doing things differently in a world that didn’t feel like it was built for her son.

“I was mad with determination,” she said. “It’s this kind of determination … that I’m going to make a difference.”

Marsha explained that behind this determination was a need for more education and more resources. She said she felt there needed to be more than one option for mothers facing this diagnosis.

“I want the next woman who’s gonna come through here to have something they can refer to … It shouldn’t be just this,” Marsha said. “People say, ‘You can just go kill it because it could be bothersome to your life and to your family.’ That’s the kind of madness I was feeling. How do I do something about this? How do I change this? This is where I live.”

That’s when Marsha realized this world wasn’t going to build itself, and she would need to be the one to build it.

Our Voice For The Voiceless

Down syndrome occurs once in every 691 live births and over 375,000 people in the U.S. have it, according to the Rocky Mountain Down Syndrome Association in Colorado. It is one of the most common genetic disorders, and 40- to- 60% of all infants with Down syndrome have some type of heart defect.

In the state of Colorado, there were 946 babies born with Trisomy 21 between 2007-2016, with only eight of those births originating in Garfield County within the nine-year span, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Trisomy 21 is the most common of the three types of Down syndrome, making up approximately 95% of cases.

Marsha said she found that the majority of resources and organizations that could have helped her throughout her pregnancy were offered in bigger cities like Denver, but she did not want to leave the county.

“How do I help that next woman who’s gonna come in? Maybe she’s an immigrant, maybe she’s a single mother, maybe she’s a wife, maybe she’s just passing through town,” Marsha said. “What are we going to do so that she doesn’t have to hear this thing about termination again?”

Marsha is a certified CNA, pastor and a mother. Her experience laid the foundation for what would soon become Our Voice For The Voiceless, a nonprofit organization dedicated to serving families of children with Down syndrome in the valley.

The organization, which has not formally launched, will offer informational materials, courses, counseling, events, and a community for parents who want to magnify the voice of their children.

Marsha emphasized that the organization will also focus on addressing early intervention – something she wished she would have known about when she learned of her baby’s diagnosis.

Marsha labels her role as a “special needs parenting strategist,” which she has used to teach mothers how to raise their children in the home, as well as how to educate them for parents who prefer homeschooling but are unsure about how to approach it.

“Yes, children with Down syndrome can learn math. The question is, are we patient enough?” Marsha said. “When (parents) know that these resources and early intervention can offset a lot of these things, there is no limit. There was never any limit, in a way.”

Even though the organization has yet to launch officially, Marsha says she’s gotten a head start speaking to parents both locally and globally since its inception in 2020.

Marsha uses her online community to talk to parents about raising children with Down syndrome. She keeps colorful pipe cleaners next to her computer that she’s used to explain the extra 21st chromosome of a child with Down syndrome to mothers who may sometimes live as far as Kenya.

“It’s the teacher part of me,” she said. “With information like this, I hope parents find it in their heart to reach out to us.”

Marsha has also worked to host events in the interim before the organization’s launch. The last event was a mother’s day brunch held in May at the Rifle Branch Library focused on mental health and wellness in the family. And of course, kids were welcome.

Marsha extends her mission to reach parents and community members through her podcast, Voice Of Hope Show, where she shares her encouragement with parents and caregivers.

“Gift from God”

Even after everything, however, Marsha made it clear that she never would have dreamt to do this on her own.

“I think I realized (all) I need is my faith,” she said. “Same thing with my husband … He went on his knees right there in the park in Carbondale. He fell to his knees and he said, ‘God, what did I do? What did I do wrong? … What did I do this time to deserve this?’”

Marsha said this question is, unfortunately, not uncommon for people who have children with disabilities. According to her experience, some people believe in the connotation that the parents must have done something wrong in order for their child to be born with Down syndrome.

“People just believe that if there’s going to be a child with special needs, Down syndrome or other things, (it means the) the parents sinned, somebody sinned, somebody did some witchcraft, there’s something gone wrong,” she said.

Marsha’s husband, however, did not stay stuck on this question. He told Marsha he heard the answer in his spirit in the form of John 9:3 in the Bible. The verse says, “Neither he nor his parents sinned, Jesus answered. He was born blind so that the works of God might be displayed in him.”

“It’s nothing that he did wrong or I did wrong that causes our child to be born with Down syndrome. It is so that God’s glory will be manifested through him,” Marsha said. “(My husband) got up off his knees and then he called me and he was saying to me, ‘Marsha, everything’s gonna be fine.’”

Through this experience, Marsha found the answer to the question she felt she’d asked too many times: what’s next? Marsha and her husband turned to their community. They reached out to their family and their pastor at the time, asking for prayers that their son be born healthy, without any heart defects or need for open-heart surgery.

To keep their mission focused while working through the emotional challenges of their son’s diagnosis, Marsha created a “health board,” inspired by vision boards she’d seen.

“I was trying to find every way in which we could keep my focus going through the pregnancy,” she said.

The health board was filled from top to bottom with quotes, bible verses about healing and ultrasound images. At the center of the board was the name of Marsha’s son — Nathan — which means “gift from God.”

“God says in Jeremiah 1:5 that he knew (Nathan) before he formed him in his mother’s womb, my womb,” she said. “That was important for me to grab onto and carry around during this pregnancy.”

When the time was nearing for Nathan to be born, Marsha said she and her husband were sent to Denver for the baby’s delivery because they were considered to be “at risk.”

“So we get there, and the baby is born. We see the baby the next day … and (the doctor) says, ‘No issues with his heart.’ And I said, ‘Can you put that in writing?’” Marsha said, laughing. “I started to lean into God to say, ‘Now, show me how to care for this child.’”

Once again, Marsha found the answer to her question in scripture. She quoted Proverbs 31:8-9: “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.”

“I love this scripture so much because if my husband and I didn’t decide to speak up for this child and say, ‘We aren’t gonna terminate him because you perceive that he’s gonna be a burden to society,’ then he wouldn’t be here,” Marsha said. “So I realized I’ve got to be the voice for those who are voiceless.”

Thus, Our Voice For The Voiceless was born.

The organization’s logo — a singular tree — represents the beauty and potential of every child to come forth and bring fruits into life.

“But when a child is in the womb, it cannot do all of this. It needs somebody to be that voice,” Marsha said. “The best person, and the first person, has got to be the parents; it’s got to be the mom.”

Marsha recalled the stories she’s heard from other parents where families were broken up because of a diagnosis.

“The husband leaves, because this is not what they want,” she said. “People have said, ‘I don’t know what to do but it’s so scary and this is not what we bargained for’ … (they) think that they lost a future … I think where it starts is that first information that is given with the diagnosis news. The picture is painted so ugly.”

The world’s view of Down syndrome

A 2012 study conducted on termination rates from 1995-2011 after a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome suggest that roughly 67% of these pregnancies end in abortion in the U.S.

This is in stark contrast from the overall number of abortions in the United States, which in 2020 was about 19.8% of all reported pregnancies according to Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The number is even higher in other countries, where nearly 100% of women in Iceland who receive a prenatal Down syndrome diagnosis choose to terminate their pregnancy, according to a 2018 article from Healthline. Denmark follows close behind with 98% of pregnancies, then France with 77%.

These prenatal screenings can help the parents prepare for the birth of a child with Down syndrome in terms of finding specialized resources, especially since people with Down syndrome have an increased risk for certain medical conditions, such as congenital heart defects, respiratory and hearing problems, Alzheimer’s disease, childhood leukemia, and thyroid conditions, according to the National Down Syndrome Society. However, these screenings can also open the door to what some health organizations call “selective abortions” due to misconceptions about Down syndrome and an absence of counseling following a positive result.

Marsha spoke of the experiences shared by followers of her online community, many of whom say they faced pressure from many directions, from their doctors to even extended family, to abort their children.

A huge part of Marsha’s work aims to combat these negative connotations so that families don’t have to face these pressures alone.

“Oftentimes people just get to be, when they have the baby. And they hold that baby in their arms, and they start to realize that, ‘I would never change this for nothing. I’m so glad I didn’t listen to my doctors,’” Marsha said while mimicking the motion of cradling a baby in her arms.

When Marsha decided to launch her organization, she said she knew she wanted it to be free of charge for parents who need resources both during and after their pregnancy.

“Whatever people need, we’re going to pool our resources. I’m going to show them that it’s possible. I’m going to show them that there’s hope, and we’re going to show them that there is a future,” she said. “Down syndrome is not the child.”

Marsha said she hopes to formally launch Our Voice For The Voiceless and all of its services in October 2024. For now, her goal is to reach organizations who are committed to the cause to foster collaboration, and to spread the word.

“If nothing else, I want people in the community to know that there is hope … You know what real, true hope is? Hope is the confident expectation that God is going to do what he says he will do,” Marsha said.

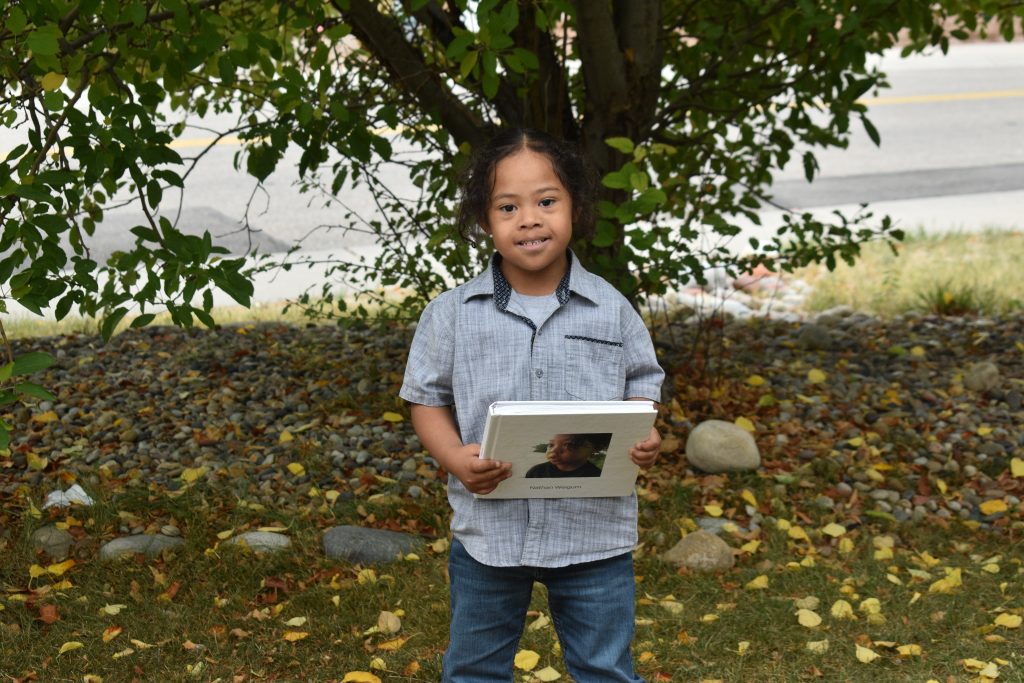

Today, Nathan is 5 years old and lives with his mother in Rifle.

“This is Nathan’s story. This is not my story. We are just speaking up for him until the day when he can speak up for himself,” Marsha continued. “You can be the voice … For me, Marsha Weigum and my husband, if we ever had to do this all over again, we would say yes.”

Marsha can be reached at [email protected].