Eye, Health Care, Symptoms, Treatment

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): Symptoms, Causes, Treatment

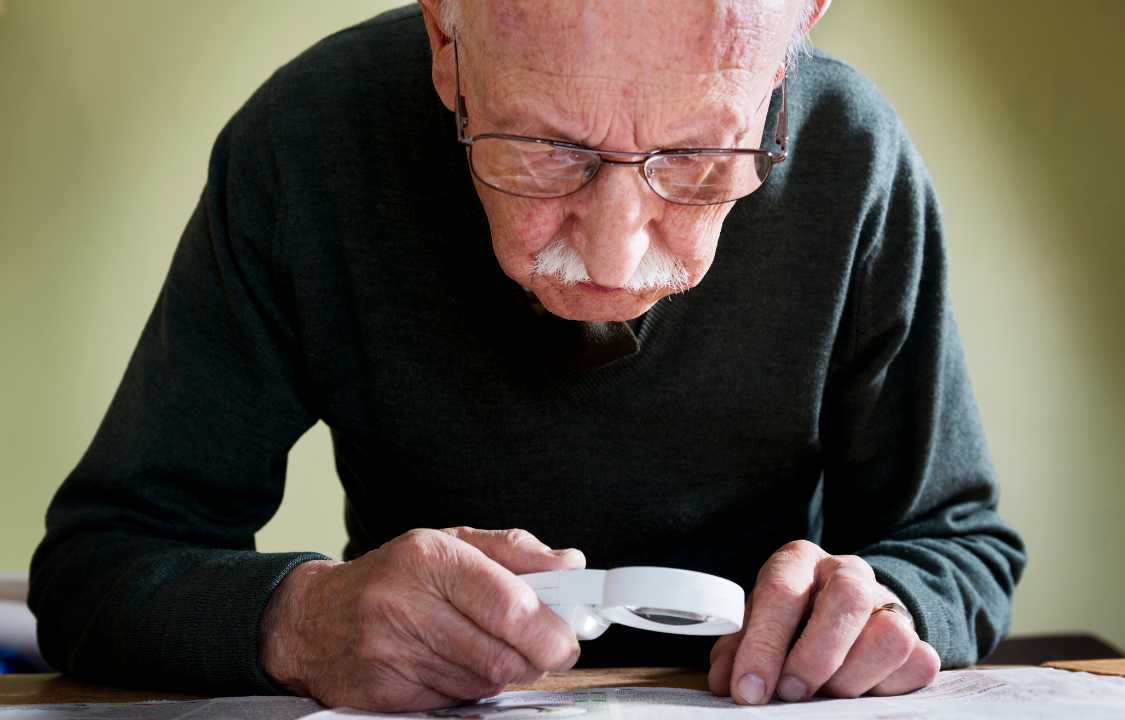

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a progressive eye disease that afflicts individuals over time, and it stands as the primary cause of irreversible vision loss in those aged 50 and above, affecting approximately 1 in 10 people in the United States. This condition manifests when the macula, which is the central portion of the retina responsible for sharp vision, begins to deteriorate. The retina, situated at the back of the eye, is the vital nerve tissue that facilitates the perception of light and image formation.

Given that this ailment unfolds as individuals age, it is frequently termed “age-related macular degeneration.” Though it seldom leads to complete blindness, it does have the potential to cause significant visual impairment, making it a condition of notable concern.

A distinct form of macular degeneration, known as Stargardt disease or juvenile macular degeneration, affects children and young adults, presenting a different set of challenges.

Signs of Age-Related Macular Degeneration often remain elusive in the early stages, and a diagnosis may only occur once the condition advances or begins to impact both eyes. Some of the common symptoms include deteriorating or less distinct vision, leading to blurry vision that can make tasks like reading fine print, driving, or recognizing faces more challenging. Additionally, individuals might notice dark, blurry areas at the center of their vision, straight lines may appear wavy, or color perception could be altered. Should anyone experience these symptoms, it is imperative to consult an eye specialist promptly.

AMD can be categorized into two primary types

1. Dry AMD: This is the most common form of the condition and is characterized by the presence of yellow deposits known as drusen in the macula. In the early stages, a few small drusen may not significantly affect vision, but as they increase in size and quantity, they may lead to dimmed or distorted vision, especially during activities like reading. Dry AMD results in gradual vision loss, as the light-sensitive cells within the macula gradually thin and deteriorate, leading to potential blind spots at the center of one’s vision.

2. Wet AMD: Although less common than dry AMD, the wet form is more aggressive, causing faster vision loss. It is characterized by the development of unstable blood vessels beneath the macula that can leak blood and fluid into the retina, distorting vision and leading to blind spots. In advanced cases, these vessels may form scars, resulting in permanent central vision loss.

Typically, the majority of individuals with macular degeneration initially have the dry form, which can later progress to the wet form. Only around 20% of individuals with macular degeneration are affected by the wet form from the outset.

While the precise causes of AMD are not yet fully understood, experts believe that genetic factors and environmental influences both play a role in its development. It is notable that wet AMD often follows a period of dry AMD, but the reverse is not necessarily true.

Several risk factors are associated with both forms of AMD. These risk factors include smoking, high blood pressure, a diet high in saturated fats, obesity, being assigned female at birth, and having fair skin.

Age-related macular degeneration is a widespread concern, with over 170 million people affected worldwide, making it a leading cause of permanent blindness in industrialized nations. Among racial groups, non-Hispanic White European individuals face the highest risk of developing AMD, followed by Hispanic, Black, and Asian populations. People over 75 are nearly 15 times more likely to develop AMD compared to those aged 50-59. Women are slightly more predisposed to AMD, but this could be due to their generally longer life expectancy.

The diagnosis of AMD often occurs during routine eye examinations in which the eyes are dilated, allowing the eye specialist to conduct a thorough assessment. Several tests can aid in the diagnosis, including:

- Retinal exam: During this examination, the doctor inspects the retina for the presence of drusen beneath it.

- Amsler grid: The Amsler grid is a checkerboard pattern of straight lines that patients are asked to observe. If the lines appear wavy or are missing, it may signify the presence of macular degeneration.

- Angiography or Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): These imaging procedures involve the injection of dye into the patient’s arm veins, allowing the doctor to capture images as the dye moves through the blood vessels in the retina. It is particularly helpful in identifying new vessels, leakage, and the type and location of the blood vessels.

Early detection of AMD is crucial, as it can help initiate timely intervention to slow its progression and mitigate its severity.

The progression of AMD can be categorized into three stages

1. Early: This stage is asymptomatic, with no noticeable symptoms.

2. Intermediate: Symptoms may vary, with some individuals experiencing central vision blurriness or difficulty seeing in dim light.

3. Late: In this advanced stage, individuals typically experience wavy lines when looking at straight objects. There may also be a central vision blur that can expand and intensify over time, resulting in a decrease in brightness perception and difficulty seeing in low light conditions.

Wet AMD, on the other hand, is considered late-stage AMD due to its aggressive nature. Dry AMD has the propensity to transition into the wet form during any of its stages.

While there is no cure for age-related macular degeneration, several treatments aim to slow its progression and preserve vision. Supplements, such as those recommended by the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), have been shown to potentially protect against the advancement of AMD, especially in cases of intermediate or late-stage dry AMD. These supplements often contain vitamins and nutrients like vitamin C, vitamin E, lutein, zeaxanthin, zinc, and copper. Nevertheless, they may not be universally effective, and it’s important to consult with an eye specialist to determine their appropriateness.

Wet AMD often necessitates the use of anti-angiogenesis drugs, which inhibit the formation of abnormal blood vessels beneath the macula. These drugs are administered through injections into the eye and have been shown to improve the vision of many individuals affected by wet AMD. Some examples of these drugs include aflibercept (Eylea), bevacizumab (Avastin), pegaptanib (Macugen), and ranibizumab (Lucentis).

There are also surgical and laser therapy options for AMD, though these are typically reserved for specific cases.

Furthermore, some individuals explore alternative treatments, including the use of herbs like ginkgo, milk thistle, bilberry, and grape seeds, or alternative therapies such as acupuncture and microcurrent stimulation, to complement standard treatments. However, it is imperative to consult with a medical professional before pursuing these alternative approaches, as they may interact with medications or carry potential side effects.

Age-related macular degeneration, while it appears to affect individuals of European descent more commonly, can impact anyone. Research has unveiled disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of AMD, particularly among people of color. Studies have revealed that Black individuals with AMD are 23% less likely to receive anti-VEGF injections, which are the primary treatment for dry AMD, as compared to White AMD patients. Latino and Asian American individuals also face lower rates of receiving this treatment. Furthermore, research indicates that Black individuals are 18% less likely than their White counterparts to undergo regular eye exams necessary for the detection of AMD. The reasons for these disparities are multifaceted, possibly encompassing factors such as access to healthcare, cultural mistrust of the healthcare system, and bias.

While age-related macular degeneration doesn’t lead to complete blindness, it can severely affect central vision and lead to permanent eye damage. Individuals with advanced AMD may find it challenging to drive, read, recognize faces, or perform various everyday tasks, potentially causing legal blindness.

Living with AMD might require seeking assistance and adapting to new ways of conducting daily activities. A balanced diet rich in antioxidants, including foods like fish high in omega-3 fatty acids, nuts, dark leafy greens, yellow/orange vegetables, and antioxidant-rich fruits, can support overall eye health.

The management of AMD can entail various costs, encompassing doctor visits, treatments, vision therapy, low-vision aids and technology, home modifications, payments for caregivers, and lost productivity at work. Treatment expenses can be significant, and the financial burden depends on one’s insurance. Without insurance, a two-year course of treatment may range from $9,000 to $65,000 per year, contingent on the prescribed treatment. However, some drug companies and organizations offer programs to assist individuals with lower income in covering these costs.

Adapting to the vision limitations that come with AMD can be facilitated by using low-vision aids, enhancing lighting in the living environment, and seeking vision rehabilitation from a specialist who can help optimize the use of peripheral vision and provide tailored advice.

Mental health concerns are common among individuals grappling with AMD, particularly if central vision is affected. This may increase the risk of depression or social isolation. Support from mental health professionals, support groups, family, and friends is essential in navigating the emotional and psychological impact of AMD.

In terms of prognosis, AMD typically worsens over time. Nevertheless, not all individuals with AMD develop the condition in both eyes or progress to the late stages. The dry form of AMD typically advances gradually over several years, while the wet type can emerge suddenly. Early treatment is crucial in preventing symptom exacerbation, and regular eye examinations are essential. Wet AMD often requires multiple treatments, and lack of follow-up treatment can result in a worse outcome.

Most people with AMD retain good eyesight, and even if central vision is lost, peripheral vision is often preserved. Advanced AMD can impact activities that necessitate sharp eyesight, such as driving or reading.

For individuals without AMD, several healthy habits can help reduce the risk of developing the condition. These habits include smoking cessation, managing underlying health conditions like high blood pressure, maintaining a healthy weight, engaging in regular exercise, and adhering to a balanced diet that incorporates antioxidant-rich foods, omega-3 fatty acids, and other nutrients that promote eye health.

Several other eye conditions exhibit symptoms similar to AMD, including macular hole, myopic macular degeneration (occurring in individuals with high myopia or nearsightedness), Stargardt disease (juvenile macular degeneration), and diabetic retinopathy, which is a complication of diabetes that damages blood vessels in the retina.

In conclusion, having age-related macular degeneration does not necessarily entail the loss of sight. Timely intervention, healthy lifestyle choices, and a supportive network can help protect central vision and overall quality of life. The journey with AMD might involve adaptations and changes, but with the right approach, independence can be maintained, and individuals can continue to enjoy the activities they love.